Yesterday was a very special anniversary in the history of dance; on this day in 1877 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake had its grand premiere at the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow. Based on Russian and German folk tales, the ballet tells the story of Odette, a beautiful princess turned into a swan by an evil sorcerer’s curse. We’re not sure exactly which folk tales inspired the ballet although “The Stolen Veil” by Johann Karl August Musaus has been suggested as a possible inspiration as has the life of the Bavarian King Ludwig II who was closely associated with swans and was possibly the prototype of one of the characters – Prince Siegfried. Tchaikovsky it was said was fascinated by Ludwig’s tragic life. The ballet was initially poorly received particularly by critics; having said that the ballet was performed by the Bolshoi for six years with a total of 41 performances – many more than several other ballets from the repertoire of this theatre, suggesting it must have had some degree of popularity. The original Odette was Anna Sobeshchanskaya who herself was not a fan of the piece. In 1895 it was revived by the legendary ballet masters Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov for the Imperial Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg, with Pierina Legnani in the lead role. Petipa and Ivanov had wanted to revive the ballet for some time and had been discussing plans to update the score with Tchaikovsky since at least 1888. In 1893 as their plans were beginning to become reality Tchaikovsky died causing a delay. His younger brother gave his blessing to continue with their plans leading to Riccardo Drigo the imperial ballet’s chief conductor and composer updating some of Tchaikovsky’s score. There were some changes from the original; in the revival the character of Odette is a cursed mortal woman rather than the fairy swan-maiden she is in the original whilst the ballet’s villain is not Odette’s stepmother (as it was in 1877); instead it’s the sorcerer von Rothbart. The original ballet was four acts – this was changed to three in the revival with act 2 become act 1, scene 2. The finale is also different; in the original the lovers drown at the hand of Odette’s stepmother whilst in the revival Odette dies by drowning herself, with Prince Siegfried choosing to die as well, rather than live without her. The Romeo & Juliet esque lovers are then reunited in an apotheosis. The ballet was a success and Pierina Legnani won critical acclaim for the role. For the next six years the ballet belonged solely to her and she was the only dancer to perform it. After she returned to her native Italy in 1901, the role was inherited by her successor Mathilde Kschessinskaya whose performance was similarly celebrated. In the century since it has become arguably the most well known ballet in the world not to mention one of the most popular and is considered a hallmark of classical ballet with it being a key feature of every major (and minor) ballet companies repertoire. The majority of stagings of the ballet nowadays are based on the 1895 revival rather than the 1877 original; nearly every balletmaster or choreographer who has re-staged Swan Lake has made modifications to the overall storyline, while still maintaining much of the traditional choreography for the dances, which is considered basically sacrosanct in the ballet world. Something you may not know about me is that I adore ballet. Like many little girls I did ballet lessons as a child and although I didn’t make it to the Royal Ballet (something 5 year old me briefly dreamed of), I still love ballet now as an adult and find it to be probably the most beautiful form of dance. To celebrate Swan Lake’s 147th birthday, I thought I’d do a post about a few of my favourite historical ballerina’s (and maybe even a contemporary one or two!). Hope you enjoy! Also on my Pinterest you’ll find an album dedicated to ballet, see here!

One of if not the most well known ballerinas of all time, Anna Pavlova was born in St Petersburg; her father Matvey Pavlovich Pavlov was a military officer whilst her mother Lyubov Feodorovna Pavlova, came from peasants and worked as a laundress at the house of a Russian-Jewish banker, Lazar Polyakov, There’s a bit of a question mark of certain aspects of her family history; it’s been claimed that her parents were married at the time of her birth however there are also claims that they didn’t marry until years later. There’s also the possibility that Pavlov wasn’t even her father; Polyakov’s son later claimed that she was his father’s illegitimate child. We do know that Anna was born premature and throughout her childhood was regularly ill, at one point being sent to the Ligovo village where she was cared for by her grandmother. In 1890 when she was 9 her mother took her to a performance of Marius Petipa’s original production of the Sleeping Beauty at the Imperial Maryinsky Theatre. Evidently the performance made an impression on Anna and she begged her mother to take her for auditions at the Imperial Ballet School. Because of her age and sickly appearance she was rejected however young Anna was clearly not as fragile as she looked and was determined to audition again. She worked on her dancing for a year before she auditioned a second time. This time she was accepted. Ballet academy turned out to be a difficult period of Anna’s life; she wasn’t a natural dancer and classical ballet did not come easily to her, partly due to her physique – she had severely arched feet, thin ankles, and long limbs which was different to the small, compact body that was considered ideal for a ballerina at the time. She was picked on by her fellow students who gave her mean nicknames such as” The broom” and “La petite sauvage”. Anna was by all accounts miserable but she was also determined. Undeterred, she worked harder than everyone to improve her technique and become the kind of ballerina she dreamed of. She was known to practise constantly, repeating the steps until she was dancing in a way she considered perfect. She took extra lessons from some of the most noted teachers of the day including Pavel Gerdt, Nikolai Legat, Enrico Cecchetti (who is considered one of the greatest ballet virtuoso’s of all time and was the founder of the Cecchetti method, a very influential ballet technique used to this day) and Ekaterina Vazem a former prime ballerina at the Imperial Ballet. Anna later said of the hard work she put into becoming the icon she did; “no one can arrive from being talented alone. God gives talent, work transforms talent into genius”. By her final year everyone was beginning to realise that Anna was special with a capital S and in that final year, she began appearing with the main ballet company. She graduated in 1899 at age 18, and was chosen to enter the Imperial Ballet a rank ahead of corps de ballet as a coryphée. She made her official début at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt’s Les Dryades prétendues (The False Dryads) in a performance that was highly praised including by hard to impress critics such as Nikolai Bezobrazov. The thing that made Anna stand out was that she was not a technically perfect ballerina, in fact she was actually quite a flawed dancer; she frequently performed with bent knees, bad turnout, misplaced port de bras and incorrectly placed tours. She was however an unbelievably charismatic performer and her style harked back to the time of the romantic ballet and the great ballerinas of old. Her style clashed with the favoured style of the imperial ballet head honcho Marius Petipa who was renowned internationally for his strict academicism and focus on technique. One of his favoured ballerina’s was Pierina Legnani whose technique was notoriously exemplary; on one occasion Anna tried to imitate Legnani’s famous fouettés, infuriating her tutor Pavel Gerdt who was furious and said “….leave the acrobatics to others. It is positively more than I can bear to see the pressure such steps put on your delicate muscles and the severe arch of your foot. I beg you to never again try to imitate those who are physically stronger than you. You must realize that your daintiness and fragility are your greatest assets. You should always do the kind of dancing which brings out your own rare qualities instead of trying to win praise by mere acrobatic tricks”. Her biggest weakness was her weak ankles which led to difficulty performing certain roles for example the fairy Candide in Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty – the steps had to be changed to fit her. Another flaw was that Anna was endearingly enthusiastic and her joy whilst dancing actually led her astray on more than one occasion; during one performance as the River Thames in Petipa’s The Pharoah’s Daughter, her energetic double pique turns led her to her losing her balance, and she ended up falling into the prompter’s box. Despite all this, Petipa grew incredibly fond of her and she soon became one of his favourites; he revised a number of ballets to suit her and taught her himself the title role in Paquita, Princess Aspicia in The Pharaoh’s Daughter, Queen Nisia in Le Roi Candaule, and Giselle. She was named danseuse in 1902, première danseuse in 1905, and, finally, prima ballerinain 1906 after a resounding performance in Giselle. She became a major celebrity in St Petersburg with her legions of fans calling themselves the Pavlovatzi. One person not thrilled by all this success was her fellow dancer Mathilde Kschessinska. You see Kschessinska was not well liked by Petipa; she had been the girlfriend of the Emperor Nicholas II prior to his marriage/accession to the throne and in the years since their break up had been the mistress of two of his cousins Sergei and Andrei. When Kschessinskaya became prime ballerina, she did so without the consent of Petipa who felt that although she possessed an extraordinary gift as a dancer, she had been given the title primarily due to her influence at the Imperial Russian Court. In 1901 she fell pregnant (the father of the child isn’t exactly clear; it was either Sergei or Andrei. After marrying the latter she would claim the baby was definitely his however prior their marriage she had been quite open she wasn’t sure who the baby daddy was) and Anna was chosen to take her place in the role of Nikiya in La Bayadere. Kschessinska, not wanting to be upstaged, was certain Pavlova would fail in the role, and so made Anna’s life as difficult as possible. She was convinced that Anna would suck as Nikiya owning her to the rigorousness of the steps, her inferior technique, her small ankles and thin legs. Kschessinska turned out to be 100% wrong and the audiences of St Petersburg were absolutely enchanted with Pavlova. Kschessinska wasn’t the only ballerina that Anna clashed with; she had a rather vicious feud with Tamara Karsavina and on one occasion during a performance Karsavina’s shoulder straps fell and she accidentally exposed herself. Anna allegedly mocked her reducing an embarrassed Karsavina to tears. Anna’s masterpiece came in 1905 when she created the role of the Dying Swan, a solo choreographed for her by Michel Fokine. The short solo was round 4 minutes long and followed the last moments in the life of the swan. It was a phenomenal success and Anna went on to perform it about 4,000 times. It’s now one of the famous solo’s in ballet. She later joined the Ballets Russe, a company founded by Sergei Diaghilev, that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. She only worked for them for a brief period of time, before she left to form her own company. The main reason she left was that she preferred the melodious “musique dansante” of the old maestros/salon style music of the 19th century and wasn’t a fan of the avant-garde scores composed by the likes of Igor Stravinsky for the Ballets Russe. The rest of her life was dedicated to touring; she spent the next twenty years touring around the world performing a repertory consisting primarily of abridgements of Petipa’s works, and specially choreographed pieces for herself. Many of these pieces were based on native dances of various countries including Mexico, Japan, China and India, four places she travelled to multiple times. Agnes de Mille wrote of her “she travelled everywhere in the world that travel was possible and introduced the ballet to millions who had never seen any form of western dancing”. Between 1912 and 1926 she did almost annual tours of the United States which won acclaim. She ended up leaving Russia as many did following the Russian Revolution and she settled as an emigre in London. While in London, Pavlova was influential in the development of British ballet, most notably inspiring the career of Alicia Markova later the principal ballerina at the Royal Ballet. This was her lasting legacy; she was responsible in the last twenty years of her life for taking on proteges and assistants, many of whom would go on to teach ballets to hundreds of students each. She also tutored young girls in Paris post WWI; at one point fifteen girls were adopted into a home she brought near Paris at Saint-Cloud, overseen by the Comtesse de Guerne. The girls in the house were supported by the money Anna’s performances made and she became well known for her significant philanthropy supporting Russian orphans after the war. Unlike some ballerina’s (I’m looking at you Kschessinska) whose private lives became noteworthy, Anna’s was not, with her focus remaining her whole life on her career. She met Victor E. Dandré a Russian government official in either 1900 or 1904 (we’re not sure which). He at some point stopped working for the government and became her manager. It was apparently known that the two were a couple, and they may have married in 1914 although we’re not 100% sure (after her death, he asserted that they had married but it wasn’t known that they were legally married before she died and no proof was ever provided afterwards). The couple remained quietly together for thirty years until her death in 1931. She died in The Hague on Friday 23rd January 1931 of pleurisy. She had apparently been ill for some time, suffering from pneumonia and whilst travelling from Paris to The Hague summoned her doctor who travelled from Paris to treat her . He told her that she needed to have an operation but that if she had the operation, she would never be able to dance again. She refused to have the surgery, saying “If I can’t dance, then I’d rather be dead.” She died not long after with Dandre, her doctor and a close friend/her maid Marguerite Létienne by her side. Allegedly her final words were “Get my ‘Swan’ costume ready.” In accordance with old ballet tradition, on the day she was to have next performed, the show went on, as scheduled, with a single spotlight circling an empty stage where she would have been. Anna’s story is amazing because this was a girl that was initially rejected from the ballet academy, only to now be considered arguably the most influential ballerina of all time.

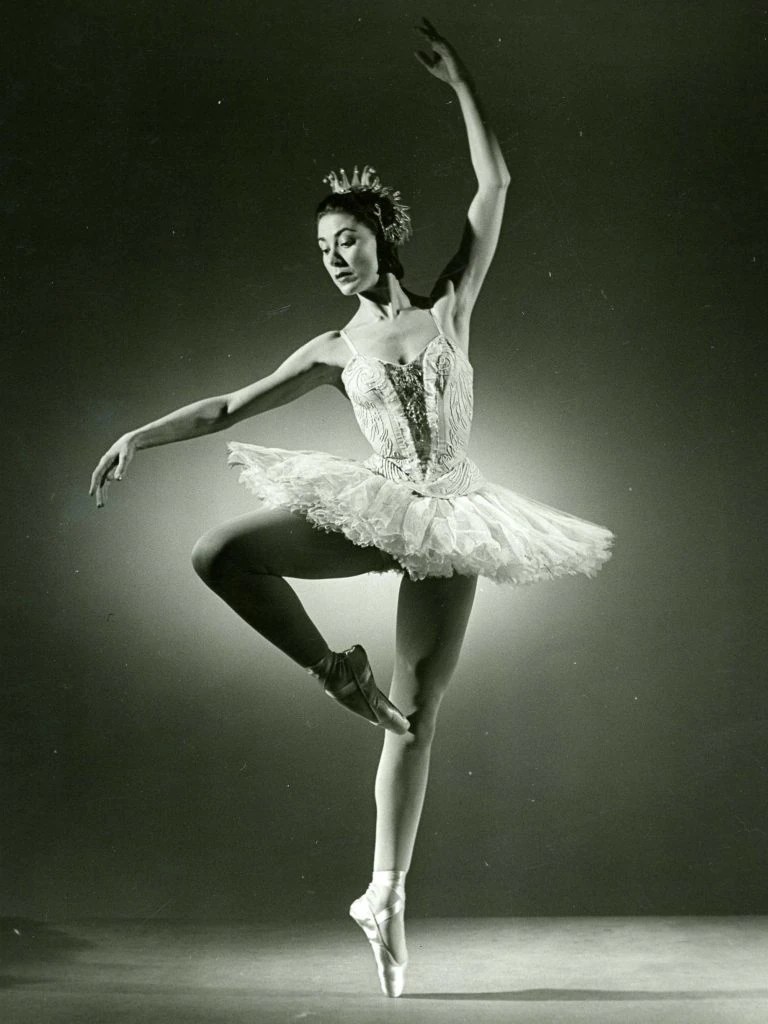

Pierina Legnani is another name which frequently pops up in the discussion of “who is the great ballet dancer of all time?”. Born on September 30th 1863 in Milan, we know very little about her background. We do however know that she began dancing at the age of 7 with a private tutor. The fact her parents could afford a private tutor suggests she came probably from some degree of money or the family was at least comfortable. After a year of private teaching, she was accepted into the La Scala School, where she would go on to receive training for the next ten years. In her final year, she acted as an understudy to the Prima Ballerina at the time Maria Giuri; she also took lessons with Caterina Beretta who helped her hone the technical expertise for which Legnani would become famous. She began dancing as part of the company and had a successful career but doesn’t appear to have set the stage on fire until she moved to London where she appeared as Prima Ballerina at the Alhambra Theatre in 1890 in the ballet Salandra by Eugenio Casati. She returned to Milan in 1892 covered in a ton of glory and was appointed Prima Ballerina immediately. London would clearly have a special place in her heart and she returned for guest appearances throughout her career including in the summer of 1893, when she danced as the Princess in the ballet Aladdin. In 1892 and 93 she also made appearances in Madrid and Paris. A few months later, Legnani was invited to Russia to join the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg. Unlike Pavlova (who might I add would have been a ballet dancer in training at the Imperial Ballet in 1893 and therefore probably saw Legnani dance), Legnani had exemplary technique, in fact her virtuoso technique was so impressive that she set the standard at the Imperial Ballet and was the main inspiration for the modern day Russian style of ballet in which dancers are expected to develop characteristic technical brilliance. She made her Imperial Ballet début in Lev Ivanov and Enrico Cecchetti’s version of Cinderella in December 1893; this night would end up being a major landmark in the history of ballet. Not only was her debut a phenomenal success with the audience enraptured by her incredible near perfect technique and dramatic acting abilities, but in the final act she astounded just about everyone by pulling off a clean 32 fouettés. This sequence has since gone on to be a famous one. You see no one and I mean no was doing 32 fouettés regularly on stage at this point. According to eyewitnesses, she performed the sequence without stopping and without moving from the spot in which she started, and the audience (including the choreographers who apparently had no idea she was planning to do 32 fouettés) were so thrilled by the fouettés that they made her repeat the sequence. Now there’s a misconception that she was the very first ballerina to do 32 fouettés; she wasn’t and she herself said “… in the last tableaux of ‘Aladdin’ I turn thirty-two pirouettes on tiptoe without dropping my foot. Not many dancers can do that“. Her saying “not many dancers” suggests there was at least some that Legnani was aware of. It certainly disputes the idea that she was the only dancer who could. More than likely she was the first ballerina to do so publicly and on a consistent basis; she was almost certainly the first to do so on the Imperial Russian stage. The known record before her was her fellow Italian Emma Bessone who performed a sequence of 14 fouettés in Ivanov’s 1887 ballet The Haarlem Tulip. As I mentioned when I was writing about Pavlova, the imperial ballet master Marius Petipa was a sucker for perfect technique and he fell completely in love with Legnani’s dancing, granting her the the official rank of Prima Ballerina Assoluta, the first ballerina to be given the honour at the Imperial Ballet. Though initially engaged for one season only, she was such a phenomenal success in St Petersburg that she ended up performing in Russia until 1901. Throughout her years in Russia, Petipa revived a number of works for Legnani, in which she created new pas and variations; these works included Coppélia, The Talisman, The Little Humpbacked Horse and Le Corsaire. She also created the lead roles in many of Petipa’s new ballets, including the White Pearl in The Pearl, Ysaure in Bluebeard and Raymonda. Her masterpiece was her performance as Odette/Odile in Petipa and Ivanov’s recreation of Swan Lake. Legnani was not only Petipa’s fave dancer, he also immensely liked her as a person, in fact Legnani was incredibly popular with her colleagues at the Imperial Theatres. This was in part due to how incredibly hard working she was with Nikolai Legat commenting that she was very keen to learn all about the style of the old French school. As a side note, Legat also says in his memoirs that his father hoped that he and Legnani would marry (which never happened); whether or not this suggests that the two were romantically involved isn’t clear. One person that wasn’t so fond of Legnani was Mathilde Kschessinska; although Kschessinska was a stunning dancer, she didn’t have the technical brilliance of Legnani and her constant name dropping when it came to her connections within the Imperial family didn’t exactly make her Miss Popular. She didn’t like playing second fiddle to Legnani and a feud developed between them, although Legnani doesn’t appear to have actively taken part in the feud. In fact it appears rather one sided on Kschessinska’s part. Eventually Legnani had enough and she left the Imperial Ballet in 1901, not solely because of Kschessinska (she was also apparently very homesick for Italy), but the escalating and increasingly rivalry with Kschessinska apparently played a role in her departure. or her farewell benefit performance, Legnani chose to dance in Petipa and Minkus’s 1872 ballet La Camargo, which told the story of how the 18th century dancer Marie Camargo and her sister Madeline were abducted for one night by the Comte de Mulen. This is such a fascinating choice; Marie Camargo was probably the most famous ballerina of the 18th century, so to have the most famous ballerina of the 19th century (aka Legnani) portray her is SO cool. Her performance was by all accounts phenomenal and a perfectly brilliant ending to one of the most legendary careers in ballet history. I mean very few people can they inspired a nation’s entire school of dance. After she left the Imperial Ballet, she didn’t initially retire, in fact she travelled around Europe, performing most frequently in Italy, London and France where she was welcomed by audiences as the Queen of Ballet. In 1910 she returned to Italy for good where she retired to her villa at Lake Como in the Northern Italian Lakes. Some time after that she became a member of the examining board of her alma mater the La Scala Ballet School, alongside Enrico Cecchetti and Virginia Zucchi. She remained in the role for two decades until four months before her death on the 15th November 1930. The last twenty years of her death, other than her role on the examining board, were incredibly private and we know next to nothing about her personal life.

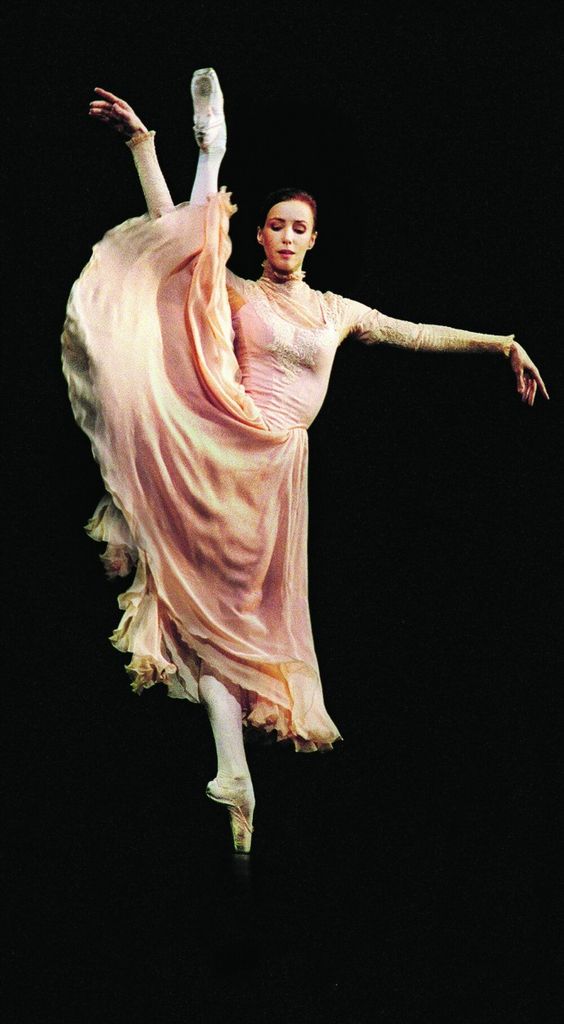

Now it’s very possible if you’re not into ballet you probably won’t have heard of a few people on this list but you’ve probably heard the name of this woman – Dame Margot Fonteyn. Born Margaret Evelyn Hookham in Reigate Surrey on the 18th May 1919, the daughter of a mechanical engineer. Her mother Hilda was the illegitimate daughter of an Irish woman, Evelyn Acheson, and the Brazilian industrialist Antonio Gonçalves Fontes. When she was four the family moved to Ealing and she began attending ballet classes with Grace Bosustow. Her mother accompanied Margot to her earliest lessons, learning the basic positions alongside her daughter in order to improve her understanding of what a ballet student needed to develop. Now Hilda became known as what we would today call an overbearing stage mum, in fact Margot’s teachers and colleagues would later refer to her as “the Black Queen” owing to her constant and overbearing presence in Margot’s dance career. Margot doesn’t appear to have minded and the two seem to have had a very affectionate relationship. In July 1924, at the age of five, Hookham danced in a charity concert and received her first newspaper review: the Middlesex Country Times noted that the young dancer had performed “a remarkably fine solo” which had been “vigorously encored” by the audience. Later on in life Margot was infamous for putting herself under phenomenal pressure; this trait was apparently prominent from a very early age and even as a child she would push herself physically to avoid becoming a disappointment to others. Whenever a dance exam approached, she became ill with a high fever for several days, recovering just in time to take the test. Some years into her training her father was transferred abroad and the family moved to Louisville in Kentucky. They then moved to Tianjin in China where they lived for a year. This was followed by a brief stint in Hong Kong before they moved to Shanghai in 1931 where she began studying ballet with the Russian émigré teacher Georgy Goncharov. His partner Vera Volkova became a major figure in Margot’s life and career. Now at this point Margot didn’t actually want to be a ballerina however her mother and Volkokva pushed her. Although she was reluctant to. continue training, she was also naturally competitive and being in a class with a student like June Brae pushed her to work harder. She was trained predominantly in the Cecchetti style (a style of training devised by the Italian ballet master Enrico Cecchetti); she disliked the drill style training and preferred the fluid expression of the Russian style. When she was 14, her mother brought her back to London to pursue her ballet career whilst her father remained in Shanghai. This proved to be a questionable decision and in 1934, her life was turned upside down when her father abruptly wrote to her mother confessing that he had been having an affair and had fallen in love. In the letter he asked for a divorce so that he could marry his new girlfriend. He remained in Shanghai until after World War II (during the war he was interned by the invading Japanese) when he returned to England with his new wife Beatrice. Having returned to London, Margot began studying with Serafina Astafieva a Russian dancer who had once been a dancer at the Ballet Russe. She was then poached by Ninette de Valois who invited the young girl to join the Vic-Wells Ballet School (later known as the Royal Ballet School). There she trained under Olga Preobrajenska and Vera Volkova who had also moved to London. Her first solo performance occurred in 1933, as an actress rather than a dancer, using the interim name Margot Fontes, as a child in the production of The Haunted Ballroom by de Valois. Her first dancing performance took place a year later in 1934, as a snowflake in The Nutcracker. She used the surname Fontes which was apparently the surname of relatives; her mother wrote to those relatives, requesting their permission for Margot to use the name for her stage career. They said no (an answer I’m guessing they later regretted) probably due to the family’s wish to avoid an association with a theatrical performer; in the 1930’s the occupation was judged by some parts of society. Hilda and Margot subsequently looked up variations of Fontes in the telephone directory, choosing the more British-sounding Fontene and adding a twist to make it Fonteyn. Her brother, Felix, who became a specialist of dance photography, eventually adopted the same surname. In 1935, Fonteyn had her solo debut, playing Young Tregennis in The Haunted Ballroom. That same year, Frederick Ashton created the role of the bride in his choreography of Stravinsky’s La Baiser de la Fée specifically for her. Though Margot demonstrated elegance and technical ability, she lacked polish and Ashton later said she had a “brittle stubbornness” which negatively impacted her dancing. In 1935 Alicia Markova the Prima Ballerina of the company left the Vic-Wells and Fonteyn was one of the dancers that filled her spot. She soon began to emerge as the most talented of the bunch and quickly rose to the top of the field of dancers. In the summers of 1935 and 1936, in order to up her game, she spent time in Paris where she studied with the exiled Russian ballerinas Olga Preobrajenska, Mathilde Kschessinska (yes her again!!) and Lubov Egorova. They encouraged her to emphasise her delicate and somewhat feline grace and use to her advantage; Ashton was clearly happy with this and often cast her as a frail or otherworldly being. In 1936, she was cast as the unattainable muse in his Apparitions, a role which consolidated her partnership with Robert Helpmann and the same year played a wistful, poverty-stricken flower seller in Nocturne. This particular performance was a major turning point for Margot as it cemented her place as the heir to Markova. The company then began experimenting with televised performances, accepting paid engagements to perform for the BBC at Broadcasting House and Alexandra Palace; Margot danced her first televised solo in December 1936, performing the Polka from Façade. Now one of the things that Robert Helpmann is most renowned for is his performance in The Red Shoes (aka one of my favourite films ever); Helpmann was an exemplary actor who preferred theatrical/comedic roles to classical ballet. Throughout the 30’s he was her main partner and he was key to helping her develop her theatricality. She would later name him her favourite dance partner. Someone else who was key to her development was Leonard Constant Lambert a composer and conductor who co-founded the Royal Ballet and was its music director. He was key to developing her musicality. Margot fell head over heels in love with Lambert and the two began a volatile relationship that would be on and off until his death in 1951. One of the main reasons for the volatility of their affair was the fact that he was married with a child. For years he refused to leave his wife and friends of hers would later admit that she was devastated when she realised he would never marry her. She allegedly admitted decades later, years after his death and her marriage that he was the great love of her life. Even after he and his wife divorced in 1947 he still didn’t marry Margot as she hoped and instead married the artist Isabel Delmer. Meanwhile he had another mistress in the form of the dancer Laureen Goodare; whether Margot knew about Laureen isn’t clear however his relationship with Margot was evidently not a secret in fact in 1938 he dedicated his score for the ballet Horoscope to her. Regardless he clearly never deserved my girl Margot who adored him until his death. In 1938 she first met Roberto Arias an 18-year-old law student from Panama who was studying at Cambridge University. Fonteyn became enamored with Arias after seeing him perform a rumba dance at a party and the two had a summer fling before he returned to Panama. His subsequent lack of communication left her gutted. Remember him though, he becomes important to her story later on!! By 1939 Fonteyn had performed the principal roles in ballets such as Giselle, Swan Lake and the Sleeping Beauty leading to her appointment as the Prima Ballerina of the Vic-Wells, soon to be renamed the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. Her performance in Swan Lake was a huge moment in her career and convinced critics that a British ballerina could successfully dance the lead role in a full-length classical Russian ballet. Throughout World War II the company danced nightly, sometimes also performing matinées, to entertain troops; the company suffered in these years. Not only were dancers exhausted but the company lost many of its male dancers to the armed forces. Shows either had to be carefully chosen or edited to help ensure that an almost entirely female cast could perform all the roles or young, inexperienced male dancers were pulled straight from ballet schools, to dance in ballets they were absolutely not ready to appear in. In 1943 Margot’s relationship with Lambert began to deteriorate; he was drinking heavily, becoming sloppy with his other affairs and their fights were getting worse. In August of that year, Margot took an unexplained sick leave from the company for two months, missing their opening season performances. No one was entirely sure where she was or what she was doing. Friends and people in the ballet world (not to mention the vast majority of her biographers since) were convinced that she had fallen pregnant with Lambert’s child and had taken time off to have an abortion. Concerned at the increasing volatility of the Fonteyn-Lambert relationship her mother set her up with the film director Charles Hasse and encouraged her to end her relationship with Lambert. Although Fonteyn and Hasse became lovers, and remained together for about four years, she did eventually go back to Lambert. During the war, Ashton created roles for her such as his bleak wartime piece Dante Sonata (1940) and the glittery The Wanderers (1941). She also performed notably in Coppelia imbuing the role with humour. In 1946, the company moved to the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden (where it remains); one of her first roles was at a command performance of Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece The Sleeping Beauty as Aurora with King George VI, Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mary, the princesses Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) & Margaret and the Prime Minister Clement Attlee in the royal box. Now obviously 1946 was only a year post the end of the year and the costuming department at the ballet was still impacted by post-war rationing. In order to make the costumes worthy of royalty, the company had put out a call for every available scrap of silk, velvet or brocade, cutting up and re-purposing old opera costumes, furs and even velvet curtains to create a lavish production. For Margot there was the small challenge that that no other English ballerina had The Sleeping Beauty their repertoire and so unlike the Russian ballerina’s, who traditionally learned roles from previous generations of dancers, Fonteyn had had to figure out the role of Aurora by herself. This was a daunting task but may actually have been a blessing in disguise as it allowed her to create her own interpretation. It was a huge success and the ballet became a signature production for the company. It also became a distinguishing role for Fonteyn, and marked her arrival as the new Queen Bee of English ballet. The late 40’s were a super busy time for Miss Fonteyn; not only did she dance on television to mark the re-openig of the Alexandra Palace but she also danced as the miller’s wife in The Three Cornered Hat by the choreographer Leonide Massine and was the lead in the abstract debut of Scenes de Ballet which Ashton wrote for her. He also created Symphonic Variations for her to capitalize on the success of The Sleeping Beauty. She travelled to America for the first time in 1949 where she reprised the role of Aurora in 1949. She instantly became a celebrity and The New York Herald Tribune called her a star with critic writing “London has known this for some time, Europe has found it out and last night she definitely conquered another continent.” In 1948, at the opening night of Frederick Ashton’s Don Juan she tore a ligament in her ankle which prevented her from dancing for several months (this meant she missed the premiere of Cinderella). Luckily she recovered in time to go to America. Upon her return she danced in George Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial and appeared as Sleeping Beauty in a tour of Italy with and Pamela May. She made her first tv apperance in America on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1951 and her performances were credited with improving the popularity of dance with American audiences. This was followed by two of her most noted roles, as the lead in Ashton’s Daphnis & Chloe in 1951 and Sylvia in 1952. She was honoured as Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1951 for her contributions to British ballet; she subsequently considered retiring owing to a) the frequent injuries she had begun to struggle with and b) the fact her most frequent partner Michael Somes was beginning to take less challenging roles. Now remember Roberto “Tito” Arias the Cambridge Uni student who she had a summer fling with before he went back to Panama and conveniently forgot to write? Well whilst on an American tour in 1953, she found herself suddenly bumping into him when he surprised her with a visit to her dressing room after a performance of Sleeping Beauty. In the years since they’d last seen each other, Arias had married, had children and become a politician and Panamanian delegate to the United Nations. He had evidently become somewhat regretful about not writing to Margot and despite being married, he began courting Margot. Eventually he did what Lambert had never done and asked his wife for a divorce; this led to them marrying in 1955. Between 1953 and 1955 she won significant praise for her performances in Entrada de Madame Butterfly, later called Entrée japonaise and the Firebird. Shortly after her marriage she returned to the stage and found success in St. Petersburg, dancing the role of Medora in Le Corsaire opposite Rudolf Nureyev. A year later she and Michael Somes were guest artists featured in Act II of Swan Lake, at the wedding of Grave Kelly and Prince Rainier III of Monaco. Between 1954 and 1959 she and Somes appeared in several Producers’ Showcase productions, including television productions of Cinderella and the Nutcracker. She became a freelance dancer in 1959 which allowed her to accept the many international engagements she was offered. The following few years were tricky for her; shortly before her marriage Fonteyn had been selected to become president of the Royal Academy of Dance; she protested not wanting the appointment, however the academy overruled her decision. She was given further unwanted duties as the wife of a diplomat after her husband was appointed an ambassador to the court of St James. She however had absolutely no interest in politics which earned her considerable criticism and caused a number of small controversies; after performing in Johannesburg, South Africa, she was criticized for performing, despite the dancers’ union ban because of apartheid. She was then criticised for performing for Imelda Marcos, attending a party at which drugs were used (she was actually detained for the incident), dancing in Chile during the military dictatorship and becoming friendly with Hope Somoza the wife of Anastasio Somoza Debayle the President of Nicaragua whose appointment as President was of questionable legality. In 1959 her husband was involved in a coup d’etat against the Panamanian president Ernesto de la Guardio which led to her being arrested, detained for 24 hours in a Panamanian jail, and then deported to New York City where she confessed to the British ambassador to Panama Sir Ian Henderson that she had known about the plot. It was following this that everyone including the head of the Royal Ballet Ninette de Valois became convinced that she was on the verge of retiring. In 1961 Rudolf Nureyev the star of the Kirov Ballet defected in Paris and was invited by de Valois to join the Royal Ballet. She offered Margot the opportunity to dance with him in his debut, and though reluctant because of their 19-year age difference, Margot agreed. On the 21st February 1962, Nureyev and Fonteyn made their debut together, performing Giselle to an enthusiastic capacity crowd, for which they received 15 minutes of applause and 20 curtain calls. The performance was described by one journalist as “otherworldly”. Frederick Ashton was understandably thrilled to have the best female ballerina and the best male ballet dancer in the world at his disposal and immediately choreographed Marguerite and Armand for them. It was an immediate success and this was the beginning of arguably the most famous partnership in ballet history. Part of its success Michael Somes later said was because they were two stars of equal talent who pushed each other to their best performances. They would dance together constantly for a decade between 1962 and 1972; one reason for this was that in 1964 her husband was shot four times by a rival Panamanian politician; he was left a quadriplegic for the rest of his life and Margot had to continue dancing in order to pay the medical bills. Although he used a wheelchair, he would travel with Margot for most of her travels which took her around the world with Nureyev. During their partnership they were noted for their performances of all the classics especially Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake; La Bayadère, Giselle, and Marguerite and Armand and Raymonda also formed the foundations of their repertoire. When Nureyev choreographed new productions of Raymonda and Swan Lake, he insisted she serve as his partner. In 1965 the couple debuted the title roles in Romeo & Juliet choreographed by Sir Kenneth MacMillan; a year after the debut, the production was still drawing queues for its nightly performances. One of Margot’s greatest assets as a ballerina was her acting abilities which made her performance unique and set Juliet apart as one of her most acclaimed roles. Despite the 19-year-age gap and the significant differences in their personalities (Margot was infamously methodical whereas Nureyev was was wildly exuberant and a little chaotic), the two became devoted to one another. Their loyalty was so great that Fonteyn would not approve an unflattering photograph of Nureyev, nor would she dance with other partners in ballets within his repertoire. The actual extent of their relationship is not 100% clear; Nureyev was gay and in two long term relationships with men; one with Erik Bruhn between 1961 and 1986 when Bruhn died and one with Robert Tracy between 1978 and his own death in 1993. Despite this he had later admit to having sexual relationships with a number of women; one of these women he confessed was Margot Fonteyn although she denied it. Biographers are split on whether they did or they didn’t; in 2005 one dancer who performed with them claimed she had overheard them discussing a pregnancy and subsequent miscarriage, an apparent result of a sexual relationship whilst Nureyev’s assistant later said that he wanted to marry Margot. Regardless of whether they did or didn’t they were evidently devoted to one another and Nureyev later gave one of the dreamiest quotes about her saying “at the end of Lac de Cygnes, when she left the stage in her grand white tutu, I would have followed her to the end of the world”. He also said Nureyev said that they danced with “one body, one soul” and one of Margot’s biographers, said of them “most people are on level A. They were on level Z”. In 1965, Fonteyn and Nureyev appeared together in the recorded versions Les Sylphides, and the Le Corsaire Pas de Deux, as part of the documentary An Evening with the Royal Ballet. The film grossed over US$1 million, creating a record for a dance film at the time. She went into semi retirement in 1972, relinquishing parts in full ballets and limiting herself to only a variety of one-act performances. She also did one off performances exploring other styles of dance including contemporary. In 1976, she published her autobiography although it included none of the more scandalous parts of her life; her affair with Lambert for example and the question of a potential abortion was not mentioned nor was discussion of a possible relationship with Nureyev. She retired for good in 1975. For her 60th birthday, Fonteyn was feted by the Royal Ballet, dancing a duet with Ashton in his Salut d’amour and a tango from Ashton’s Façade with her former partner Helpmann. At the end of the evening, she was officially pronounced prima ballerina assoluta of the Royal Ballet. In a bizarre change of occupations she and her husband retired to a Panama cattle farm where they became cattle ranchers. In her retirement she worked occasionally; in 1979, Fonteyn wrote The Magic of Dance which was aired on the BBC as a television series in which she starred and was published in book form. The six-part series, explored aspects in the development of dance from the 17th to the 20th century across the world and covered a number of performers including herself, Nureyev, Fred Astaire, Isadora Duncan, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Sammy Davis and Marie Taglioni. She also published Pavlova: Portrait of a Dancer, in 1984, as a homage to Anna Pavlova. Her final performance was in Mantua, Italy in 1988 along with Nureyev and Carla Fracci. In 1989 her husband died; around the same time Margot was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She had spent pretty much all of her savings on her husband’s medical care and so had very little for herself; she ended up having to sell her jewellery to pay for her care. This happened partly because she refused to tell anyone she was sick; Nureyev was one of the few people she told of her problems and he arranged to visit her regularly in Houston, despite his busy schedule as a performer and choreographer. He also anonymously helped to pay the bills. Eventually it became public knowledge and the Royal Ballet put on a gala to raise money for her care; Placido Domingo sung, her former partners Somes and Nureyev danced and the event was attended by Princess Diana, Princess Margaret and Dame Ninette de Valois. Ultimately it ended up raising a quarter of a million pounds to go towards her care. From 1990 onwards her health deteriorated and she corresponded regularly with the likes of Queen Elizabeth II and the President of Parma who both sent frequent flowers and well wishes. She died on the 21s February 1991 in Panama City; shortly before her death she converted to Roman Catholicism so that she could have her ashes buried in the same tomb as her husband’s. A memorial service was held for her on the 2nd July 1991 at Westminster Abbey. Nureyev was said to be devastated by her death, however owing to his own ill health (he was suffering from AIDS) he was unable to attend.

An overwhelming criticism usually levelled at ballet is that it’s one of the least diverse types of dance. In recent years in fact ballerina’s like Misty Copeland (whose African-American) have been open about their struggles. It’s fascinating then that one of the earliest prima ballerina’s at the American Ballet Theatre was herself a woman of colour. Maria Tallchief was born Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief in Fairfax, Oklahoma in January 1925 to Alexander Joseph Tall Chief and Ruth Porter; her father was Native American as a member of the Osage Nation. She grew up in quite a wealthy prestigious family; her paternal great-grandfather, Peter Bigheart, had helped negotiate for the Osages concerning oil revenues that enriched the Osage Nation. In her autobiography, Tallchief explained, “As a young girl growing up on the Osage reservation in Fairfax, Oklahoma, I felt my father owned the town. He had property everywhere. The local movie theater on Main Street and the pool hall opposite belonged to him. Our 10-room, a terracotta-brick house stood high on a hill overlooking the reservation.” Growing up her mother Ruth had dreamed about becoming a performer, but her family had been poor and unable to afford dance or music lessons. As a mother she was determined that her daughters would not suffer the same fate and Maria was put into dance lessons at the tender age of 3. Her early teachers were not good and she later quipped that she was lucky they hadn’t done any real damage. In 1933, the family moved to LA with the intent of getting the children into the Hollywood musicals that were all the rage. musicals. The day they arrived in Los Angeles, her mother asked the clerk at a local drugstore if he knew any good dance teachers and the clerk recommended Ernest Belcher, father of dancer Marge Champion who agreed to take her on. At this time Maria was removed from pointe training, probably saving her from major injury. Maria was not just a gifted dancer but immensely intelligent; in Oklahoma she had skipped several grades but in LA she was put back in her normal grade however she was so far ahead that she often finished her work before everyone and then walked around the playground whilst everyone else finished. Bored with school, devoted herself to dance in Belcher’s studio. In addition to ballet, which she had to relearn from the beginning due to the poor training she had received in Oklahoma, she also studied tap, Spanish dancing, and acrobatics. She found acrobatics very difficult and eventually quit the class, but later in life put the skills to good use. Aged 12, Tallchief began to work with Bronislava Nijinsky, a renowned choreographer who had recently opened her own studio in Los Angeles, and David Lichine a dancer and choreographer who had at one point danced with Anna Pavlova. Nijinska imparted a strong sense of discipline and the belief that being a ballerina was a full-time task; it was only whilst working with Nijinska that Maria began to consider ballet as a full time career. Another one of her teachers was Mia Slavenska who took a shine to Maria and and arranged for her to audition for Serge Denham, director of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. He clearly didn’t think as highly of her as nothing came of it. In 1942 after graduating high school she went to New York at the age of 17. She immediately looked up Serge Denham but he didn’t remember her and his secretary told her that the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo didn’t need any more dancers. Luck however was on her side; the company was about to embark on a Canadian tour but most of Denham’s dancers were Russian émigrés who didn’t have passports so he needed dancers asap. Maria luckily had a passport; based on a combination of her talent and her passport, she was taken on as an apprentice. After the Canadian tour, one of the dancers left the troupe due to pregnancy and Tallchief was offered the dancer’s place and a $40 per week salary. On her first day as a full member of the company, Tallchief was thrilled to find out that her mentor Nijinska was in charge of staging Chopin Concerto for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and she soon cast Maria as the understudy to the lead ballerina. Her early years in the Ballet Russe was not fun; the Russian ballerinas frequently feuded with American ballerinas (mostly because they viewed them as inferior); when Maria was promoted by Nijinsky she became the leading American ballerina in the company and thus the primary target of the Russian’s hostility. Within her first two months at Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, she appeared in a staggering seven different ballets as part of the corps de ballet. In the summer of 1944 George Balanchine a choreographer who had begun his career in ballet but had spent the preceding decade being a choreographer on Broadway and in Hollywood, was hired by Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo to work on a new production. This was a life changing moment for Maria both personally and professionally. He immediately began assigning her important parts; she performed solo’s in Song of Norway, a pas de trois with Mary Ellen Moylan and Nicholas Magallanes in Danses Concertantes and in a pas de deux with Yurek Lazowsky. He then agreed to a long term contract; after a while it became clear to everyone, except Maria that Balanchine had a thing for her. The Washington Post at the time referred to her as his “crucial artistic inspiration”. Although the two became friends she seems to have been totally unaware that his feelings towards her were more than friendly (I should note that Balanchine was known to have a thing for his dancers; he was married four times all to dancers that worked under him and he had dozens of affairs with young ballerina’s. A love affair with Balanchine however came with risk. Years after Maria, he fell in love with an American ballerina Suzanne Farrell and then ruined her career; as Clive James wrote “the older he became, the more consuming his love affairs with his young ballerinas … when Suzanne Farrell fell in love with and married a young dancer, Balanchine dismissed her from the company, thereby injuring her career for a crucial decade”). At this point he was married albeit separated to his second wife ballerina Vera Zorina. In 1946 his divorce to Zorina became final. He promptly turned around and asked Maria to marry him. To say she was shocked is an understatement and she initially asked for time to think it over. After a few weeks she agreed (which makes me think she was maybe a little more aware of his interest than she let on) and they married on August 16th 1946. Her parents were furious; when she told them about the engagement, her mother allegedly said “I’ve never heard of anything more … idiotic […] What’s wrong with you?”. When they married she was 21 and he was 42. Her parents continued to oppose the marriage and did not attend the wedding. Balanchine quickly her mentor and told her in order to be the best she needed to start from scratch; under his tutelage, Maria lost ten pounds and elongated her legs and neck, she learned how to hold her chest high, keep her back straight, and keep her feet arched and relearned the basic exercises the way Balanchine wanted. The same year they married Balanchine joined with arts patron Lincoln Kirstein to establish the Ballet Society (which would later turn into the New York City Ballet). Maria stayed with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo until her contract expired in 1947; when it did she joined Balanchine in France where he was working as a guest choreographer at the Paris Opera Ballet. Whilst in Paris she impressed with roles in Le baiser de la fee and Apollo. The French press were fascinated by her background and emphasised her Native American ancestry with headlines including “La Fille du Grand chef Indien Danse a l’Opera” (“the daughter of the great Indian chief dances at the opera”) and “Peau Rouge Danse a l’Opera pour le Roi de Suede” (“Redskin dances at the Opera for the King of Sweden”). Maria and Balanchine were only in Paris for six months before returning to New York where she became one of the first stars of the New York City Ballet, which opened in October 1948. Balanchine’s choreography was different to other choreographers and stood out from the classics; his pieces emphasised athleticism, speed, and aggressive dancing in a way that was wholly unique. Maria who maybe wasn’t the most classical of ballerina’s was well suited for Balanchine’s vision. During her time as the principal dancer at NYCB Balanchine both re-worked classics for her and composed new roles specifically for her. Her most prominent roles included the Swan Queen in Balanchine’s version of Swan Lake, Eurydice in Orpheus and the lead roles in “Prodigal Son,” “Jones Beach,” “A La Françaix” and Sylvia Pas de Deux”. Her fiery, athletic performances helped establish Balanchine as the era’s most prominent and influential choreographer. Their professional relationship endured even after they amicably split up and had their marriage annulled in 1952 (they split allegedly because both had fallen for other people). She was remarried to Elmourza Natirboff, a pilot not long after but that marriage didn’t last long ending in divorce in 1954. A year later she married Henry D. (“Buzz”) Paschen Jr a businessman that she remained married to until his death in 2004. Two of her most famous performances during the late 40’s and 50’s was in the ballet “The Firebird” in 1949 and Balanchine’s adaption of The Nutcracker in 1954. Her role in The Firebird created a sensation and launched her to the top of the ballet world, granting her the prima ballerina title; one critic wrote of her performance “she’s asked to do everything except spin on her head, and she does it with complete and incomparable brilliance.” Her performance in the Nutcracker on the other hand helped transform the work into an annual Christmas classic, and the industry’s most reliable box-office draw. She remained with the New York City Ballet until she and her husband decided to have a baby in 1959 (although during the 50’s she did guest appearances with the Chicago Opera Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet and the Hamburg Ballet). After leaving the New York City Ballet and having her baby, she joined American Ballet Theatre first as a guest dancer then as prima ballerina; whilst there she expanded her repertoire taking on dramatic roles that were different to the abstract roles she’d performed for Balanchine. These roles included Birgit Cullberg’s Miss Julie and Lady from the Sea, as well as the melancholy heroine of Antony Tudor’s Jardin aux Lilas. She also began working on television performing on The Ed Sullivan Show and in specials with Rudolf Nureyev and in the musical movie Million Dollar Mermaid. She ended up relocating to Germany, briefly becoming the lead dancer of the Hamburg Ballet; she was the first major American ballerina to dance throughout Europe and South America, Japan, and Russia. One of her last performances was a 1966 title role in Peter van Dyk’s Cinderella, before she retired from dancing; she was determined not to dance beyond her prime. After retiring from dancing, Tallchief moved to Chicago, where her husband was from. She served as director of ballet for the Lyric Opera of Chicago from 1973 to 1979 and in 1974 she founded Lyric Opera’s ballet school, where she taught the Balanchine technique. With her sister Marjorie, she founded the Chicago City Ballet in 1981 and served as co-artistic director until the company closed in 1987. From 1990 until she died in 2013 she was the artistic adviser to Von Heidecke’s Chicago Festival Ballet. In December 2012 she broke her hip; she died months later in April 2013 from complications stemming from the injury. Maria is considered super important to American ballet; she was the USA’s first major prima ballerina, and was the first Native American to hold the rank. She remained closely tied to her Osage ancestry her entire life and was famed for speaking out against stereotypes and misconceptions about Native Americans on many occasions.

Alicia Markova was born Lilian Alicia Marks on the 1st December 1910 in London, the daughter of Arthur Marks and Eileen Barry; her father was Jewish and her mother converted upon their marriage. Alicia was thus raised Jewish in the Finsbury Park area of London. The family didn’t have a ton of money and what they did have have went on medical care for Alicia who was a sickly child. She began to dance on medical advice as a child in order to strengthen her weak limbs. She made her stage debut at age ten, performing the role of Salome in the pantomime Dick Whittington and His Cat. She was billed as Little Alicia the child Pavlova, due to her physical resemblance to Anna Pavlova. Alicia’s parents made contact with Princess Serafina Astafieva a Russian ballerina living in London; Astafieva was a retired dancer of the Ballet Russes, a renowned ballet company founded by Sergei Diaghilev. After arriving in London, Astafieva had established the Russian Dancing Academy at The Pheasantry on the King’s Road in Chelsea. After speaking to Alicia’s parents, she agreed to tutor the younger girl. Astafieva’s would later be responsible for teaching a number of notable British dancers including Margot Fonteyn and Anton Dolin. When Alicia was 13, Diaghilev made a visit to London in search of new talent for his ballet company and stopped by Astafieva’s studio. He was immediately impressed with Alicia and invited her to join the Ballets Russes which was based in Monaco. Her parents agreed and she became a member of the company in 1925, one month after her 14th birthday. Due to her age, Diaghilev had to specifically choreograph a number of roles for her; he also adapted a varied repertoire of established pieces to suit her. As a member of the company she came into contact with some of the biggest artistic names of the 20th century including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky and George Balanchine. She remained with the company until Diaghilev’s death in 1929. She then returned to London where she became the principal dancer at The Ballet Club, a company founded by Dame Marie Rambert. She formed a close bond with the then unknown Frederick Ashton; at the time he wasn’t prominent however their partnership and the copious pieces he choreographed for her won him immense praise and he went on to become one of Britain’s most celebrated choreographers. In 1931 Ninette de Valois founded the Vic-Wells Ballet in premises at Sadler’s Wells theatre in London. Now Ninette de Valois and Alicia knew each other; they had danced together at the Ballet Russes and when de Valois asked Alicia to join her new company, Alicia agreed. Frederick Ashton also joined the company and became the resident choreographer and Artistic Director. Two years after joining the company Alicia was appointed the prime ballerina; Anton Dolin was her male counterpart and the pair formed a famous partnership. The company would later change its name and is now known as the Royal Ballet. In 1932 she saw the Camargo Society performance of Giselle with Olga Spessivtseva and Anton Dolin. The ballet had at this point not been danced in England for many years and Alicia saw untapped possibilities with it. She danced it for the first time on New Years Day in 1934 at the Old Vic. The ballet was a phenomenal success and became one of the most adored pieces in the English repertoire; for example in 1942, three different companies in London were dancing the ballet. In time it became Alicia’s most treasured role and she continued to develop her performance throughout her career; she also became renowned for her performances in The Dying Swan and Les Sylphides. In 1935, Markova and Dolin left the Vic-Wells ballet to form their own touring company known as the Markova-Dolin Company and began touring around Europe for two seasons. In 1938 she re-joined the Ballet Russe and embarked on a world tour as the company’s star ballerina. The company was the first major company to tour ballet throughout the United States, and took the art form to audiences who had never seen ballet before. She began spending significant time in America especially New York and during this time, became a key figure in the formation of the American Ballet Company, now one of the most prestigious dance companies in the US. She was a contributing artist during its early years and her star power helped establish the company. In 1950, Markova and Dolin became the co-founders of the Festival Ballet, a company formed to celebrate the imminent Festival of Britain. Dolin was to be the company’s first Artistic Director, with Markova as Prima Ballerina. The company was created with the intention of performing specifically for audiences that would otherwise be unable to experience ballet; they went on to tour extensively to less traditional locations both domestic and international. It also established a number of educational programmes designed to make ballet accessible to new audiences. In 1989, the Festival Ballet was renamed English National Ballet to reflect the company’s role as Britain’s only classical ballet company dedicated to touring ballets nationwide at an affordable price for audiences. She remained the Prima ballerina until 1952, after which she continued to appear regularly as a guest dancer until her retirement from professional dancing which happened in January 1963 when she was 52. She didn’t completely disappear from the dance world and continued to play an active role in the ballet and theatre industry as a teacher, director and choreographer. She was responsible for staging a number of ballets that she had performed with the Ballets Russes. She also coached up and coming dancers and was later appointed Professor of Ballet and Performing Arts at the University of Cincinnati. This wasn’t her only academic role; she was a regular member of the teaching faculty for residential ballet courses such as the Yorkshire Ballet Seminars and the Abingdon Ballet Seminars, and was also President and a regular guest teacher at the Arts Educational Schools in London. She was also heavily involved with the Royal Ballet School in London and would go on to serve later on in life as, the President of the English National Ballet, a Governor of the Royal Ballet and Vice-President of the Royal Academy of Dancer. Like Pierina Legnani she never married and very little is known about her personal life. Alicia Markova died on the 2nd December 2004 in a hospital in Bath, one day after her 94th birthday. At her funeral dancers of the English National Ballet performed extracts from the ballets Giselle and Les Sylphides. She is now considered one of the greatest ballerina’s of the 20th century, as well as the first British dancer to become the principal dancer of a ballet company and, with Margot Fonteyn, one of only two English dancers to be recognised as a prima ballerina assoluta

I just told you a lil bit about wife number 3 of George Balanchine, well allow me to introduce you to wife 4, Tanaquil Le Clercq. Born in Paris the daughter of Jacques Le Clercq, a European American intellectual who was a professor of French at Queens College and his American wife Edith Whittemore. Although born in France she spent her childhood in New York where she studied ballet with Mikhail Mordkin. In 1941 when she was 12 she won a scholarship to the School of American Ballet. When she was 15, famed choreographer George Balanchine asked her to perform with him in a dance he choreographed for a polio charity benefit. In the ballet he played a character named Polio, and Le Clercq was his victim who became paralyzed and fell to the floor (this becomes relevant later on!!!) Then, children tossed dimes at her character, prompting her to get up and dance again. The two became close and he became her mentor; she was considered his first creation, the first ballerina to be trained in his style from childhood and she was one of his most important muses, together with Maria Tallchief (wife number 3) and Suzanne Farrell (almost wife number 5). She joined the New York City Ballet and became the principal dancer at the age of just 19; choreographers like Balanchine, Jerome Robbins and Merce Cunningham all choreographed ballets for her. One of my favourite description’s of Tanaquil was by her friend Allegra Kent who described her as “a sparkling swirl of pink tulle studded with jewels, a slender rainbow of a girl”. Unfortunately despite her talent, her career never took off the way some of the others on this list did. This was because in 1956 whilst the company were travelling around Europe she fell ill whilst in Copenhagen. It turned out to be polio; she was so ill that in a strange turn of events she became paralysed just as her character had the first time she danced with Balanchine. For a time she was paralysed from the neck down however she eventually regained most of the use of her arms and torso. Devastatingly she remained paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of her life, which ended her career. The most tragic thing is that she was literally in line to get the polio vaccine before the company departed for the tour but at the last minute changed her mind! Incredibly after regaining the use of her arms and torso years after her illness, she began teaching with one student recalling that she “used her hands and arms as legs and feet.” She taught at the Dance Theater of Harlem from 1974 to 1982. Now remember Balanchine? Well they married in 1952 not long after his divorce from Maria Tallchief. They remained married until 1969 however Balanchine (who I tbh really don’t like as a person) was not the faithful husband type and especially after her paralysis, was majorly unfaithful. In 1969 he fell for Suzanne Farrell and forced Tanaquil into agreeing to a quickie divorce. Farrell then married someone else so he got his comeuppance I suppose. She died of pneumonia in New York Hospital at the age of 71 in 2000.

I don’t know about any of you but I really love Letterboxd (if you wanna check out my profile you can here). On the site you choose your four favourite films. Mine change constantly but one of my absolute favourites is The Red Shoes (1948). If you’ve seen it, you’ll recognise this woman above. Moira Shearer King was born in Fife, Scotland in 1926 the only child of civil engineer Harold Charles King and Margaret Crawford Shearer. In 1931 her family moved to Northern Rhodesia for her father’s work and she began receiving her first dance training under a tutor who had themselves being trained by Enrico Cecchetti. She was taught in the Russian style. After five years in Northern Rhodesia the family returned to Scotland. In 1936, her mother took her to the London studio of the Russian ballet master Nicholas Legat; the studio manager, assuming that Shearer was a beginner (due to her age and size), referred them to Flora Fairbairn who specialised in teaching young dancers starting out. Three months later, by chance, Legat saw Shearer dance in a private recital and reportedly remarked, “This is no beginner”. He then took her on as a personal pupil. Whilst studying with Legat she met Mona Inglesby who gave Moira her first major role in her new ballet Endymion, presented at an all star matinee at the Cambridge Theatre in 1938. After three years at the Legat studio, she joined the Sadlers Wells Ballet School at the age of 14. The war interrupted her studies and she briefly returned to Scotland however then joined Inglesby’s International Ballet for its 1941 tour around England and West End season before she moved onto Sadlers Well’s in 1942. Her post war breakthrough came in March 1946 when she was chosen to perform as Princess Aurora, the lead female role in The Sleeping Beauty. Margot Fonteyn had danced Princess Aurora on the gala opening night a month prior followed by Pamela May who took the role the following night, and Shearer assumed the role a week later. Her performance was acclaimed. In her first few years as a principal dancer she impressed with performances in Frederick Ashton’s Symphonic Variations (which debuted at Covent Garden in April 1946, with Fonteyn in the lead female role) and as Swanhilda, the principal female role in Coppelia. Now the prima ballerina at the time was Margot Fonteyn. Shearer was one of several dancers who emerged post the war as possible contenders for Fonteyn’s crown. These dancers included Beryl Grey and Violetta Elvin. Fonteyn understood that they were a threat and noted so decades later in her autobiography writing of Moira that she was “a real threat to my position. Moira was young, fresh, beautiful and different.” Despite this the two had a decent personal relationship and were both colleagues and competitors. She came to major international prominence when in 1948 she was cast as the lead in Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (which is AMAZING. If you haven’t seen it you should). The film was critically acclaimed at the time and is even more so now; it’s widely considered one of the best films of all time and the 16 minute dance sequence is just phenomenal. This led to her focusing more on movies than ballet. In 1950 she married journalist and broadcaster Ludovic Kennedy. She retired from ballet just three years later wanting to focus on starting a family. They went on to have four children; a son and three daughters. She carried on acting however, appearing as Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the 1954 Edinburgh Festival and working with Powell again in the films The Tales of Hoffman in 1951 and Peeping Tom in 1960. The latter film was super controversial at the time – the film is about a serial killer who murders women while using a portable film camera to record their dying expressions of terror, putting his footage together into a snuff film used for his own self pleasure. This might not sound controversial now but it was incredibly so in the late 50’s, early 60’s and majorly damaged Powell’s career. Nowadays it has a cult following and is considered the first slasher film.