It’s that time again, boys and girls, here’s another Dear Hollywood post for you. I do love doing these posts especially as the current amount of content in regards to period dramas, is disappointing to say the least! I was especially disappointed at the recent cancellation of Starz’ Becoming Elizabeth; although the show had it’s issues (SPOILER ALERT – Elizabeth & Seymour did not sleep together in real life fyi), it showed an under-represented era of Elizabeth’s life and I adored some aspects of it i.e the portrayal of Edward I thought was great as were the relationships between Elizabeth and Mary and Elizabeth and Robert 💕. I thought the finale really laid the ground work for Mary’s reign which would have been AMAZING to see. We need more period dramas asap people.

If you’ve read my recent post about Double Crowned Queens or had a look at my instagram recently, then it’s likely you’ve seen my posts on this girl Emma of Normandy. Emma’s recently appeared in Vikings Valhalla on Netflix but she’s not the main character and so her screen time is unfortunately quite limited; the show also isn’t the most historically accurate tv show I’ve ever seen. Emma is absolutely deserving of being the star of her own show. Born in 984 the daughter of Richard I Duke of Normandy and his wife Gunnor (her origins are unknown for certain although we’re pretty sure she was likely Danish). As a teenage girl she was married to the King of the English Aethelred II (also known as Aethelred the Unready) who was twenty-eight years her senior and a father of ten children from his first marriage; they had three children together. In 1015 Cnut the King of Denmark and Norway began to complete his father’s conquering of England (his father had started said conquering a few years earlier); now at this point Aethelred was basically on death’s door and thus unable to really do anything remotely kingly. Responsibility for England fell to Emma who managed to hold Cnut back from entering London. We’re not entirely sure what happened when Cnut did eventually enter London as the new King; what we do know is that Cnut and Emma shocked everyone by marrying; what we don’t know is in what circumstances. Although Emma and Cnut’s marriage was a political strategy, it became a loving and seemingly happy marriage and the two had a son Harthacnut and a daughter Gunhilda. Through her marriage to Cnut, Emma was Queen of England, Queen of Denmark and Queen of Norway; she was a very prominent and politically involved Queen who held significant power, more so than she’d had when married to Aethelred. Cnut frequently left England to attend to his other territories and it’s widely believed she was left as regent in his absence. She was a significant patron of the church and appears alongside him on the frontispiece of the New Minster Liber Vitae; sources at the time describe her basically as being Cnut’s partner in power. On his death she was powerful enough to take hold of the royal treasury at Winchester, and was for a number of decades the richest woman in England. They were married between 1016 and 1035 when Cnut died; upon his death she chose their son Harthacut as the new king rather than her sons with Aethelred or Cnut’s sons from his first marriage. Her eldest son Edward never forgot that she’d chosen his half brother nor did he ever really seem to forgive her either. Now, Harthacnut was not immediately crowned; he was stuck in Denmark dealing with rebellion. Emma was designated as regent in his absence however Harold, Cnut’s son from his 1st marriage tried to claim the regency for himself. After the death of Harold in 1040, Harthacut was crowned King and Emma was finally Mother of the King. A year later in 1031, with Harthacut’s health declining, Emma convinced him to invite her son Edward back to England. This juggling of sons is SO complicated. Clearly keen to ensure England remained ruled by one of her sons, Edward was named heir to the throne upon his return. Harthacnut died in 1042 and Edward was crowned a year later in 1043. Evidently there was some tension between Edward and Emma (as I said he never forgave her for choosing Harthacnut over him) as he bizarrely accused her of treason and deprived her of her lands and titles. He changed his mind soon afterwards and everything was restored to her.

The thing about Emma’s life is that, a bit like Eleanor of Aquitaine, there’s multiple different phases worthy of their own show and I’m not sure you could feasibly do a show that encompassed the decades she spent in power. Or I mean you could but it would be very long and typically tv shows don’t run for more than a few seasons nowadays (unless you’re Greys Anatomy, NCIS, Law & Order etc). You could very well do a mini-series based on Emma’s youth and have her marrying the much older Aethelred and becoming a wife, step-mother and queen, just as a teenager. The show could be based on her first tenure as Queen and maybe end when Aethelred dies or when she marries Cnut thus remaining England’s number one girl. Alternatively you could do a mini-series which starts with her marriage to Cnut; you could show their marriage growing from a politically convenient arrangement to a marriage that seems to have been genuinely happy and affectionate, the way she ruled in his absence when he went abroad to his other territories (he was also King of Denmark & Norway), the complicated inner workings of the pre-conquest English court and the complications that arise with having multiple heirs (her sons, Cnut’s sons and the one son they shared). There’s just so much you could show. If you want another option then I suppose you could even do post Cnut’s death and all the shenanigans over sons and step-sons and the succession. Emma and Eleanor are the same, in that, their golden years when it would have been perfectly reasonable for them to have taken a step back and chilled a bit, were just as messy as the earlier phases of their lives. Widowhood did not slow either of these ladies down. I also think it’d be nice to see more English history pre-conquest. I’m still waiting for a huge scale big budget tv show or film about the Conquest itself. That would be particularly epic, I think!!

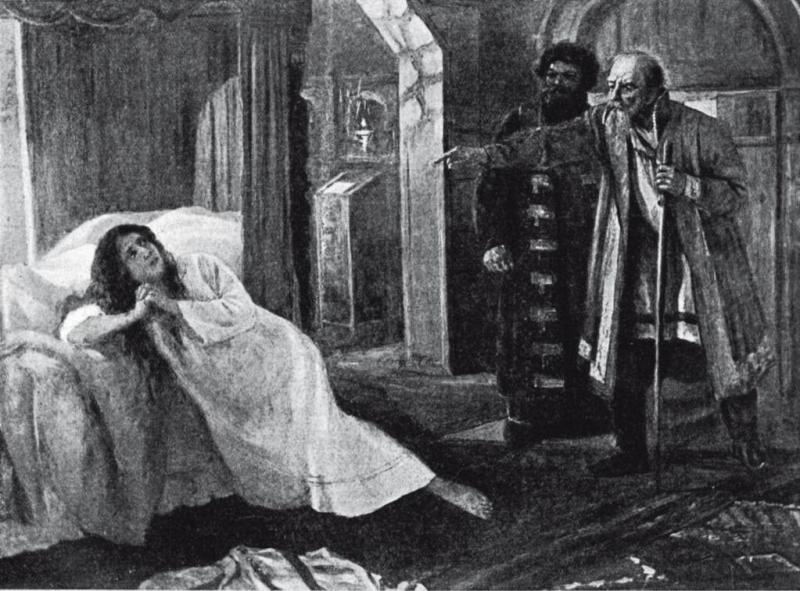

There are very few people alive, that haven’t heard of Ivan the Terrible however an awful lot of what many people have heard is hyperbole or myth; in the life of Ivan the Terrible there is a very thin line because fact and faction. I often find that one of the less talked about aspects of his very complex character, especially in the UK, is the fact that he (possibly) had eight wives (take that Henry VIII). The whole eight wives thing was a tad controversial; not only because the Orthodox Church wasn’t a huge fan of remarriage (although for a monarch in need of an heir, getting married twice was less of a problem) but the church did not consider more than three marriages legal (“the first marriage is law; the second an extraordinary concession; the third is a violation of the law and the fourth is an impiety, a state similar to that of animals”). Ivan is a fascinating historical figure but so are his wives and they deserve to be represented. Anastasia Romanovna Zakharyina-Yurieva was wife number 1 and easily the love of his life; she was the daughter of the boyar Roman Yurievich Zakharyin Yuriev who was from a minor branch of a noble family that was prominent at court and her uncle had been one of Ivan’s guardians after his father’s death when he was 3. It’s therefore possible that Anastasia and Ivan knew each other before late 1546/early 1547, when Anastasia took part in a bride show (which was basically when a large number of suitable brides – estimates suggest between 500 to 1000 girls – were brought to the Kremlin for Ivan to choose from). He chose Anastasia and they were married in February of 1547. They would go to have six children – three sons and three daughters. One of their sons was Ivan’s successor Feodor. Ivan by all accounts was very in love with Anastasia and she was a moderating influence on his pretty volatile character with Sir Jerome Horsey writing “he being young and riotous, she ruled him with admirable affability and wisdom”. There’s certainly contemporary evidence that proves his mental health although always volatile, became truly unhinged and tyrannical after her death in August of 1560. Ivan suffered a complete emotional collapse and became convinced that she had been poisoned. He had no evidence of this at the time (that didn’t stop from having a significant number of boyars tortured and executed. It also didn’t stop from establishing the Oprichniki aka a personal police force that terrorised Ivan’s enemies). Interestingly enough Anastasia’s remains were re-examined in the 1990’s and it was determined that Ivan actually may of been right after all, with Anastasia’s mercury levels being sky high – suggesting mercury poisoning. Anastasia’s now considered an important figure in Russian history – during its history Russia had been ruled by two dynasties the Ruriks and the Romanov’s; Anastasia was a Rurik through her marriage to Ivan and a Romanov by birth. After her son Feodor died without a clear successor, Russia descended into absolute chaos, in a period known as the Time of Troubles, only emerging from the ashes under the rule of the Romanovs with the first Romanov tsar, being her great nephew Michael I. She thus acts as a link between the two royal families. Next up was wife number 2 – Maria Temryukovna, who was born Qochenay bin Teymour, the daughter of Temryuk of Karbardia. It’s been alleged that Ivan quickly came to regret marrying her although we cannot be sure for certain; contemporary reports suggest she was illiterate and that many at court considered her vindictive and manipulative. She allegedly struggled to integrate to the Muscovite way of life, was unhappy at having to convert to Orthodoxy (and struggled to adapt to the religion) and failed to bond with Ivan and Anastasia’s children. She was in favour of the establishment of the Oprichniki and was said to encourage Ivan’s worst impulses. The difficulty with Maria is that all contemporary reports about her are stained by two things a) racism – she was pagan and therefore there was a high level of suspicion and discrimination against her from the great go and b) in the eyes of the Russian nobility and public, she paled in comparison to the sainted Anastasia. She died at the age of 25 in circumstances that are a lil bit messy to put it mildly. Ivan believed she had been assassinated and had various boyars tortured and executed; stories in the centuries since have accused Ivan himself of killing her although there’s no contemporary sources to suggest that’s true. Wife number 3 was Marfa Vasilevna Sobakina the daughter of a Novgorod based merchant. Like Anastasia who had been presented to Ivan in a bride show, Marfa was also chosen in similar circumstances (although there is some different – whilst Anastasia was chosen from between 500-1000 girls, Marfa was one of twelve finalists). Marfa and Ivan married on the 28th October 1571 however Marfa died just sixteen days later. Ivan’s paranoia at this point was off the charts and he once again suspected murder, even going as far as to execute his former brother in love Mikhail Temrjuk (brother of wife number 2 Maria) for his apparent involvement. One rumour that emerged after her death was that Marfa had been unintentionally poisoned by her mother who gave her some sort of medicine to increase her chances at fertility. Next up on Ivan’s never ending stream of wives was Anna Alexeievna Koltovskaya. Now this marriage was the first that the church objected to and Ivan actually married Anna without the church’s blessing. Afterwards he organised an meeting in the church of the Assumption in Moscow where he gave a heartfelt speech allegedly moving the prelates to tears (I believe he gave a speech, however I’m less convinced the priests actually cried). The church agreed to the marriage on a number of conditions including that he not attend religious services until Easter. Within two years, Ivan had evidently tired of her, allegedly due to her inability to have a child although it’s likely there were other factors. He repudiated her and sent her to a convent where she assumed the monastery name of Daria. Out of his eight wives, only she and his final wife outlived him. We know even less about wife number 5 Anna Vasilchikova whose origins are unknown. All we seem to know about her is that he once again tired of her quickly and the two were only married for just under 2 years before she was sent off to a convent like her predecessor.

The next two wives Vasilisa Melentyeva and Maria Dolgorukaya are complicated because we’re not even 100% they existed; neither women were included in official court documents nor do either women have a grave. There’s absolutely no mention anywhere in contemporary sources of Maria however there are two minor mentions of Vasilisa, whose referred to as Ivan’s concubine rather than wife. I tend to think Vasilisa probably did exist and was probably Ivan’s concubine (I doubt they were married). If she failed to have a child, then it’s not surprising she wasn’t included in official court documents. I’m not personally convinced Maria Dolgorukaya existed though. The next (and final) wife we know definitely did exist – Maria Feodorovna Nagaya – her origins aren’t super clear either but we know for a fact she was real and the pair married in 1581. Their son Dimitry was born a year later. The marriage (unsurprisingly) was not a particularly happy one and it’s believed the birth of her son was the only reason Maria was never dismissed from court. She outlived him and had quite an interesting life afterwards; her step-son Feodor succeeded her husband and the regency council that ruled for him granted her an allowance but forced her to leave Moscow (she had been left out of Ivan’s will and thus had no money of her own). Her son Dimitry was granted control of the city of Uglich (despite being a lil kid) and she accompanied him there with her brothers. In 1591 her son died (apparently due to epilepsy) and a commissioned was set up to investigate the sudden death. Maria and her brothers supported the rumour that Dimitry had been murdered on the orders of Feodor’s regency council in particular it’s leader Boris Gudunov. The rumours caused riots in Uglich which culminated in some of Gudunov’s allies and supporters having their homes attacked. Unhappy at the whole disaster, Gudunov had Maria and her family brought back to Moscow; her brothers were then imprisoned whilst she was forced into a nunnery. In the early 1600’s there was a pretender who later became known as False Dimitry I, who declared that he was the supposedly-dead prince and claimed that he had escaped the assassination attempt against him, a decade before. After the attempt, he supposedly fled to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth where he was supported by a vast amount of the Polish nobility. In 1604 Maria supposedly met the pretender incurring the wrath of Gudunov who questioned her personally, however she denied meeting the man pretending to be her son and eventually returned to the convent. In 1605 False Dimitry claimed the throne and Maria caused quite the controversy by leaving the convent and publicly identifying the pretender as her son. She accompanied him into Moscow and her family reaped the rewards of the scandal; they were freed from their various imprisonments, re-instated in their ranks, given positions within government and property confiscated by the council was returned to them. The False Dimitry did not remain in power for long. In 1606 he married Marina Mniszech, a Catholic noblewoman. According to Russian imperial tradition, when a tsar married a woman of another faith, she had to convert to Orthodoxy (see Ivan’s second wife Maria who was originally Pagan); the fact that Marina did not infuriated the Orthodox Church, the public and Ivan’s lifelong enemies the boyars who spread the rumours that Dimitry had obtained the support of Polish King Sigismund and Pope Paul V by promising to reunite the Orthodox Church and the Holy See. That same year her sons body was exhumed to prove that the Pretender was in fact a Pretender and not really Maria’s son. Very little is known about happened to Maria after her (fake) son was deposed; we don’t believe she died until 1608 so it’s likely she returned to the convent. Now there have been tv shows about Ivan that have included his wives however the shows have always centered around him with the women in his life serving as background characters. I’d love a show that focused on them specifically with Ivan in a supporting role, perhaps a short 10-episode season per woman. Not only would a show properly explore the background/personality of each woman but it would also demonstrate how each woman dealt with Ivan, as well as demonstrating how his mental instability only worsened over time. Obviously the easiest wife to portray would be Anastasia because we have a far more in depth knowledge of her than the others who were less prominent in affairs of state and married to him for fewer years; there’s also the fact that she was a Romanov and that fact was emphasised by later generations of the family who ruled Russia. As a side note – that period of history in Russia is super interesting; I was ranting slightly on twitter the other day that English-adaptions of Russian history are nearly always limited to Catherine the Great or the last Romanov’s which is insanity considering the abundance of material you could adapt (I mean the Time of Troubles, The Rurik period (pre Romanov), Peter the Great’s rise to power and the regency of his half sister Sophia Alekseyevna are just a few of the options).

When it comes to all-powerful papal families, your first thought is probably the Borgias although the Orsini’s (who produced five popes), the Medici’s (who produced two), the Della Rovere’s (who also produced two) and the Piccolomini (who also produced two) are also worth a mention and actually had more power over a longer period of time than the Borgias. Before those families were causing chaos in Rome however, there was the Theophylacti family. The Theophylacti were the most powerful family in papal politics in the period known officially as the Saeculum Obscurum. Less officially it’s known as the Pornocracy or the Rule of the Harlots. Yes you read that correctly. The Saeculum Obscurum was a period of papal history between the death of Pope Formosus in 896 and the death of Pope John XII in 964; during those seventy years, there were 19 (!!!) popes and absolute chaos reigned in Rome; of those 19 popes, 12 of them were effectively chosen and controlled by the Theophylacti family, in particular two rather extraordinary and very very controversial women; Theodora and Marozia. Now Theodora was the wife of Theophylact I, Count of Tusculum who held considerable sway of papal affairs whilst Marozia was their daughter. Theodora had huge influence over her husband who allowed her to do just about whatever the hell she wanted. In 905 at the age of around 15, Marozia became the mistress of Pope Sergius III who just happened to be Theophylact’s cousin; he also at the age of 45 was thirty years her senior. Sergius gave great influence to Marozia and her family and her father was appointed to various high positions, being promoted to the point that he effectively controlled Rome. Four years later in 909, Marozia was married to Alberic I of Spoleto although it’s possible she continued a relationship with Sergius. She and Alberic would have five sons John, Alberic, Constantino, Sergio and David/Deodatus and at least one daughter who Theodora and Marozia tried to marry to either Stephen Lekapenos or Constantine Lekapenos the sons of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos. It’s been claimed that her eldest son was actually the son of Pope Sergius III although there’s very little proof and it doesn’t appear that the claims were hugely widespread at the time. Certainly Alberic seems to been convinced John was his son; some historians tend to agree with him whilst others do not. Edward Gibbon said that Alberic was likely the father whilst Horace Mann said that Liutprand of Cremona’s report about John’s parentage “must be regarded as highly doubtful”. If Sergius was indeed John’s father then that gave Marozia and her family a bit of leverage; the Pope having a child was embarrassing to say the least. Now the impressive thing about Theodora and Marozia was the huge sway they had over the Papacy during the The Saeculum Obscurum; the first pope was obviously Sergius who Marozia was the mistress of. He was followed by Anastasus III whose candidacy was approved by Theodora (it’s also possible he was the illegitimate son of Sergius) and then Lando who was also a candidate of Theodora’s choosing. Both Anastasus and Lando were the pope for very brief periods of time. He was then followed by Pope John X who it’s believed was a distant relative of Theodora’s and a particularly close ally of her husband’s; it was also alleged that they were lovers although that’s unlikely. John began his time as Pope with three significant supporters – Theodora, Theophylact and Marozia’s husband Alberic. Theodora died in 916 and Theophylact died in 925. Alberic died later that year. That left Marozia as the supreme power player in Rome; in his book The Birth of the West, Paul Collins described her as “an extraordinary woman, her importance lies not in her paramours, but in the fact that she continued the tradition of the Theophylact clan in maintaining stability in Rome and the Patrimonium…She understood that the sexual was political and was able to use this to her advantage in a patriarchal world. Obviously beautiful and alluring to men, she was also intelligent, strong-willed, and independent like her mother.” John’s tenure as Pope came to an abrupt end in 928 when he had something of a falling out with Marozia; the throne of Italy at the time was contested (it to be quite honest was absolute pandemonium) and John invited Hugh of Provence to be the next King of Italy although Rudolph II of Burgundy also laid claim to Italy. Whilst that was all going on Marozia was remarried to Guy of Tuscany whilst led to somewhat of a power struggle with John X who made his brother Peter the Duke of Spoleto instead of one of Marozia’s sons. Marozia as you can imagine was unimpressed to say the least. The power struggle between Marozia and John X came to a bloody conclusion in 928 when Marozia and her husband staged a coup and attacked the Lateran Palace with a bunch of mercenaries. John was thrown in prison where he remained until his death; the date of which is unknown. The two most likely scenarios are that a) he was imprisoned for a short period of time before being smothered in his cell or b) he died in 929 over a year after his deposition, not as a result of violence but as a result of illness caused by the conditions of his incarceration. John was swiftly followed by Leo VI and Stephen VII both of whom were regarded to be Marozia’s puppets and were pope’s for very short periods of time.

After Stephen’s death, Marozia managed quite an impressive task – she managed to have her eldest son John elevated to the Papacy despite the fact he was only 21. Around the same time she married Hugh of Arles (her husband Guy of Tuscany had died in 929). Remember when I said the throne of Italy was hotly contested? Well Hugh was one of the various men that had claimed the throne a decade earlier and at the point of their marriage was King of at least part of Italy. He was also Guy’s half brother. Yep you read that correctly. She married her brother in law. Now whilst in Rome Hugh managed to get into a pissing match with Marozia’s son Alberic II, who I’d like to add did not have a particularly good relationship with his mother. So much so that he ended up organising an uprising against his mother and step-father. Although Hugh was able to escape, Marozia was captured and imprisoned by her own son. She would spend five years in prison until her death; in those five years her husband and son continued quarrelling; her son Alberic seemingly inherited his mother’s ability to take control and he was soon the de-facto ruler of Rome. He chose the next four popes Leo VII, Stephen VIII, Marinus II and Agapetus II. Alberic died in 954. A year later his son John XII (aka Marozia’s grandson) became Pope. The identity of John’s mother is unknown; it’s possible he was the son of Alberic’s wife Alda of Vienne (if she is indeed his mother then that’s very awkward because she was not just Alberic’s wife, she was also his step-sister, as the daughter of Hugh of Arles aka Marozia’s third husband/Alberic’s nemesis) or there’s also the possibility he was the son of one of Alberic’s concubines. If John’s mother was indeed Alda then he was around 18 when he became Pope which is just insanity. If he was the son of a concubine then he was likely around the age of 25. John XII is widely regarded as the final pope of the Saeculum Obscurum although Theodora and Marozia’s influence would remain long after they were dead; in 974 another of Marozia’s grandsons was elected as Benedict VII (he was the offspring of her middle son David) whilst in 1012 Marozia’s great-grandson Theophylact was elected as Pope Benedict VIII (he was the son of Gregory Count of Tusculum who was the younger son of Alberic and Alda); he was succeeded in 1024 by his own brother Romanos as Pope John XIX meaning two of Marozia’s great grandsons were Pope. John XIX was then succeeded by his nephew Pope Benedict IX who was the son of Alberic III and therefore the great-great grandson of Marozia. In 1058 Benedict’s nephew (and Marozia’s great-great-great grandson) was elected as Benedict IX although he was opposed by a rival faction that elected Nicholas II instead, and proceeded to chase Benedict out of Rome. He’s now generally regarded as anti-pope. I would honestly do just about anything to have the Saeculum Obscurum adapted into a tv show with a focus on Marozia. I mean the woman turned the Papacy into a family business. The only issue is that there isn’t a phenomenal amount of contemporary sources and many of them include outright slander – Liutprand of Cremona wrote extensively about Marozia and Theodora, the latter of whom he described as a “shameless whore… [who] exercised power on the Roman citizenry like a man”, however it’s very important to remember that he was a partisan of Marozia’s third husband Hugh of Arles and he LOATHED both Theodora and Marozia. He’s the principal source for the idea that Marozia’s eldest son John was the illegitimate son of Pope Sergius III despite the fact that John was born in 910 whilst Luitprand wasn’t born until 920. Despite that, I think there’s enough sources to write an incredible show about the way Marozia managed to control the Papacy, even after death. You’d also need very good historical advisors who could offer educated guesses to cover what we can’t discern from contemporary sources. The 900’s are an under-represented era in period dramas which is really quite stupid because SO much was going on.

When it comes to princesses/queens of the mid to late 1800’s, Elisabeth Empress of Austria better known as a Sissi, is the one that tends to get the Hollywood treatment, and it’s perfectly understandable why. She was a fascinating, complex creature whose story was practically made for TV. I adore Sissi and always have. Her contemporary Eugenie Empress of France (they were born ten years apart) unfortunately gets less attention. That doesn’t make her story any less interesting though and I would LOVE to see a mini-series on her. Eugenie, born Doña María Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick (a mouthful of a name) was born in 1826 in Granada Spain into a prominent family of Spanish nobility; her father was Cipriano de Palafox y Portocarrero a pro-French Spanish noble who had fought alongside Joseph Bonaparte during Joseph’s brief reign as King of Spain (whilst in battle, he lost an eye and for his sacrifice was honoured by Joseph’s baby brother the one and only Napoleon I) and who held a colossal amount of titles including Grandee of Spain (three times over), Duke of Peñaranda de Duero, Marquess of la Bañeza, Mirallo, Valdunquillo, Valderrábano, Oserea, Villanueva del Fresno and Barcarotta, Count of Montijo, Ablitas, Teba, Baños, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Miranda del Castañar, Fuentidueña and San Esteban de Gormaz and Lord of Moguer. Her mother was Doña María Manuela Enriqueta Kirkpatrick de Grevignée, the daughter of a Scottish-born diplomat who served as a consul on behalf of the United States and a French-heiress. Eugenie was her parent’s youngest child; she had an older sister María Francisca de Sales Portocarrero known amongst the family as “Paca”; it was Maria that inherited the bulk of their families titles upon the death of their father in 1839 although she was kind enough to grant Eugenie the titles of Countess of Montijo, Countess of Teba and Marquise of Ardales. Awwwww we love a sharing sister duo. Maria later became Duchess of Alba through her marriage to Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart y Ventimiglia who was the 15th Duke of Alba. In 1834 when Eugenie was 8 years old, a cholera outbreak combined with the chaos of the First Carlist War forced her, her mother and her sister to flee Spain; the First Carlist War (there would end up being three) was a civil war between two factions of the Spanish aristocracy over the succession and nature of the Spanish monarchy. There was the conservative faction who favoured the late King’s brother Carlos (they became known as the Carlists (known in Spain as the carlistas) and then there was the progressive faction that was led by the late’s king’s widow Maria Christina of the Two Sicillies who obviously favoured her daughter Isabella II Queen of Spain – the progressive faction was known as the Liberals (in Spanish they were known as the liberales or cristinos or isabelinos). Eugenie’s family were on the side of the Liberals. After fleeing Spain, Eugenie, her mother and her sister moved to Paris where she was educated firstly at the very fashionable Convent of the Sacré Cœur and then at the Gymnase Normal, Civil et Orthosomatique. Eugenie proved to be a headstrong young girl who was charming and intelligent; she was also considered physically daring and demonstrated a talent for pretty much any type of sport in particular horse riding. In 1837 her mother sent her to boarding school in England to learn English; Eugenie HATED it and was by all accounts teased relentlessly for her red hair – it’s believed they called her “Carrots” which is just plain mean. She tried to run away to India making it as far as getting on board a ship at Bristol Docks before she was stopped. She did not last in England for very long and was brought back to Paris where she was educated at home under the tutelage of two English governesses and family friends such as Prosper Mérimee and Henri Beyle. As previously mentioned her father died in 1839 and the girls returned to Madrid. Upon her return she became very interested in politics and grew close with Eleonore Gordon a former mistress of Louis Napoléon who was the son of Hortense de Beauharnais and Louis Bonaparte and thus the Bonapartist claimant to the French throne. Weird fact – his maternal grandmother Empress Josephine was also his paternal aunt by marriage because she had been married to Napoleon I who had simultaneously been Louis Napoleon’s step-grandfather and uncle. Now Eleonore Gordon was not Louis Napoleon’s only girlfriend – the boy got around and was an absolute womaniser to put it mildly. Due to her friendship with Eleonore, Eugenie became devoted to the Bonapartist cause and visited Paris again in 1849 and 1851. Her mother was a lavish society hostess and from 1847 to 1848 served as the head of Queen Isabella II’s household; leading to a friendship between Eugenie and the young Queen who was four years Eugenie’s junior. She also became acquainted with the Spanish prime minister Ramón Narváez. In 1849 she was present at a reception in Paris to celebrate Louis Napoleon becoming the president of the Second Republic. He was by all accounts instantly smitten and asked “what is the road to your heart?”. Her answer was “through the chapel, sire” which will never not make me laugh. He continued to pursue her until she eventually accepted his proposals – I’m sure her reticence to marry the man was at least partially due to his less than sterling reputation when it came to women. As I previously said the boy got around. Although he was President of the Second Republic from 1848 onwards, he staged a coup in 1851 and seized power by force, later proclaiming himself Napoleon III Emperor of the French and reviving the good old French empire of his step-grandfather/uncle; it became known as the Second Empire and he soon made it clear he wished for Eugenie to be his Empress. In 1853 he announced the marriage saying, “I have preferred a woman whom I love and respect to a woman unknown to me, with whom an alliance would have had advantages mixed with sacrifices” and they were married just a few days later. The marriage was a bit of a controversy; there had been a lot of debate around who would make the best spouse for Napoleon III and most suggestions were foreign princesses who could offer political alliances. A Spanish countess was not among the list of potential brides and Napoleon III’s insistence on marrying her was frowned upon; in France many thought Eugenie was of too little standing to marry an Emperor whilst the British continued their hatred of the French and were wholly disapproving of the Bonaparte’s (who they considered upstarts) marrying into one of the most important established houses in the peerage of Spain. If there’s one thing in history you can rely on, it’s the French and English hating on the other. Now Eugenie and Napoleon’s marriage was quite a complicated one; they really did love one another and they developed an incredibly close political partnership but there was one area where there was little agreement between them; sex. As I mentioned Napoleon had quite the sex drive whilst Eugenie absolutely abhorred sex and struggled with child-bearing. Their first pregnancy just a few months after marriage ended in a miscarriage which seems to have traumatised Eugenie slightly and put her off pregnancy completely. Napoleon III however needed an heir and so in 1355 she fell pregnant again and in March 1356 she gave birth to a son Napoléon Eugène Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte after a gruelling 22 hour labour which was by all accounts horrendous; Napoleon allegedly shouted at the physician “save the empress” when asked if he should save mother or child. Luckily both survived although Eugenie took quite a long time to recover. She then made it clear she wished never to endure pregnancy or childbirth again, and it’s widely believed sexual relations between them stopped. That meant Napoleon looked elsewhere and his list of affairs was bloody ginormous. Despite his infidelity I don’t think any of those women ever really held his heart. He seems to have loved Eugenie deeply despite their marital differences. In 1858 there was an assassination attempt against Napoleon; three bombs were thrown at their carriage culminating in the deaths of 8 bystanders and the wounding of around 140 others. Napoleon and Eugenie however were unharmed. A year or so later in 1859 Eugenie’s sister Maria fell seriously ill (she was diagnosed with TB although modern historians and physicians have said her symptoms suggest it was more likely to be leukaemia); Eugenie sent a French yacht to bring her sister to Paris where she died in September 1860 with Eugenie and their mother by her side.

Now Eugenie turned out to be a A+ empress; she was a wonderful hostess entertaining foreign and domestic dignitaries (she got it from her mama clearly), was a fashion icon (she was “perhaps the last Royal personage to have a direct and immediate influence on fashion”) and was labelled “Queen of Fashion” and “Goddess of the Bustles” by British satirical magazines, did significant philanthropic work (as a fashion icon she acquired a huge wardrobe which she disposed of in annual sales to benefit charity), established a museum of Asian art in 1863 at the Palace of Fontainebleau and travelled with Napoleon on state visits to Egypt to open the Suez Canal and Algiers; she herself also visited Constantinople (whilst there she came to literal physical blows with Pertevniyal Sultan the mother of Sultan Abdülaziz of the Ottoman Empire – Pertevniyal was said to be insulted at the having a foreign woman in the harem and allegedly slapped Eugénie across the face, almost resulting in an international incident although some sources from the time say she slapped her on the stomach instead). She was also hugely involved in politics; she was a strong advocate for women’s equality and pressured the Ministry of National Education to grant the first baccalaureate diploma to a woman. Her husband trusted her political opinions and she acted as his representative whenever he left Paris. She officially acted as regent three times – in 1859, 1865 and 1870. The last time she was regent was the last time executive power in France was held by a woman. From 1860 onwards she regularly attended meetings of the Council of Ministers and on a number of occasions lead the meetings herself. She was particularly involved in foreign policy; she tried to dissuade Napoleon III from recognising the new Kingdom of Italy and supported keeping French troops in Rome to protect the Pope’s control over the city. This led to a pretty severe clash with Victor Emmanuel II King of Italy who was quoted as saying “the emperor is weakening visibly and the empress is our enemy and works with the priests. If I had her in my hands I would teach her well what women are good for and with what she should meddle”. Ahhh good old fashioned 19th century misogyny. She also clashed with her husband’s foreign minister who was later fired by Napoleon; Eugenie was blamed for his dismissal by the Duke of Persigny who said to Napoleon “you allow yourself to be ruled by your wife just as I do. But I only compromise my future…whereas you sacrifice your own interests and those of your son and the country at large”. I’m going to assume Napoleon didn’t take too kindly to that. She was a strong supporter of the restoration of the Bourbons in her native Spain and regained an interest in Spanish politics; one of the reasons she developed such a strong dislike for the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck was his perceived meddling in Spanish affairs especially when Prussia proposed a Hohenzollern candidate for the Spanish throne. She fiercely disliked the Prussian’s and considered them a threat to her husband and son leading to her becoming one of the leaders of the pro-war camp alongside the Duc de Gramont and Emile Olliver; her faction was backed by the majority of the French military and she even admitted the personal nature of the war calling it “c’est ma guerre” (“my war”). Napoleon III was initially unwilling to commit to war although he eventually gave in. He travelled to the frontlines with their son, leaving Eugenie as Regent in Paris. In the summer of 1370 the French lost a series of battles which culminated in the resignations of the Prime Minister and the chief of staff of the army. Eugenie as regent was in a position to name a new government; her husband proposed returning to Paris after coming to the (rightful) conclusion that his presence on the frontlines probably wasn’t helping matters much. Eugenie responded with a telegram that said, “don’t think of coming back unless you want to unleash a terrible revolution. They will say you quit the army to flee the danger.” Napoleon did as he was told and remained with the army although sent their son back to Paris. With Eugenie at the helm of government and her new commander of the French military Francois Achille Bazain directing the army, Napoleon was left with very little to do and he allegedly told Marshal Le Bœeuf “we’ve both been dismissed”. France ultimately lost the war and Napoleon III was forced to surrender to the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan; Eugenie received the news on the 3rd September. Not long after hostile crowds began forming near the palace; Eugenie’s final moments as Empress were recorded by E. A. Vizetelly who recounted how her ladies, officers loyal to Napoleon, members of the government and Princess Clotilde (the wife of Napoleon’s cousin Jerome) gathered around her at the palace; “every new arrival hastened to kiss the hand of the Empress whose emotion began more and more apparent”. After news arrived that the Palais Bourbon had been invaded by revolutionaries who were on their way to Hotel de Ville to proclaim the establishment of the Second Republic, Eugenie stood up and told those surrounding her, “do not stay here longer, there is little time left”. She then bowed before them “with the stately solemn bow of impressive occasions”. In the days that followed she was forced to flee the palace with one of her entourage, seeking sanctuary with her American dentist, Thomas W. Evans who took her firstly to Deauville where he helped her board the yacht of a British official which took her to England. For almost a year her husband and his entourage were kept in relative comfort near Kassel – it’s believed Eugenie did visit him secretly. Eventually Napoleon was released and he joined her in England. In 1873 her husband died; Eugenie was too devastated to attend the funeral and in his will he wrote of her, ‘I hope that my memory will be dear to her and that when I am dead she will forgive me for whatever sorrows I may have caused her”. Which is a polite if too little too late way of saying “I apologise for being a very unfaithful spouse”. She grew close to the British royal family, in particular Queen Victoria and her daughter Princess Beatrice; Victoria and Eugenie attempted to play matchmaker and encouraged a marriage between Princess Beatrice and Eugenie’s son known affectionately as Loulou. My favourite thing about Victoria and Eugenie’s friendship is that because Eugenie was the prima donna fashion icon of the late 19th century, Queen Victoria would let Eugenie criticise her fashion sense in order to make her feel better. That’s true friendship right there.

In 1879 Eugenie’s heart was well and truly broken and completely stamped on when her only son died whilst fighting in the Zulu War. Loulou had been her absolute world and in the aftermath of his death, her health began to deteriorate. She never emotionally recovered from the deaths of her husband and son. She remained close with the British royal family and when Princess Beatrice gave birth in 1887 she not only named her daughter Victoria Eugenie but she also asked the older Eugenie to be the baby’s godmother (Beatrice it’s believed had been quite eager to marry Eugenie’s son; in her diary Queen Victoria recounted the moment Beatrice had found out about his death writing, “Dear Beatrice, crying very much as I did too, gave me the telegram … It was dawning and little sleep did I get … Beatrice is so distressed; everyone quite stunned”). Eugenie’s goddaughter would go on to marry Alfonso XIII King of Spain, the monarch of Eugenie’s native and beloved Spain. Eugenie was also friendly with the aforementioned Elisabeth “Sissi” Empress of Austria and was close with Queen Victoria’s favourite granddaughter Alix of Hesse later Alexandra Feodorovna Empress of Russia (Alexandra visited Eugenie in England repeatedly after she married Nicholas II – her last visit being in 1909). From 1885 onwards her main residence was Farnborough in Hampshire; she also had a residence in southern France and she split her retirement between the two, abstaining from politics. The outbreak of World War I led to increased political activity; she donated her personal steam yacht to the British navy, funded the construction and maintenance fo a military hospital in Farnborough Hill and made frequent donations to French military hospitals, winning her universal admiration. She died in 1920 in Madrid in her native Spain whilst visiting Jacobo Fitz-James Stuart y Falcó 17th Duke of Alba who was the grandson of her late sister Paca. Despite her love of both Spain and France, she made it clear in her will she wished to be laid to rest besides her beloved husband and son who were both interred at St Michael’s Abbey in Farnborough. Her body was transported back to England by the Duke of Alba; her requiem was attended by the British royal family including King George V. In her will she left all of her Spanish estates to her sister’s grandchildren, whilst her home in Farnborough was given to Prince Victor Bonaparte (the son of her late husband’s cousin Jerome) and her villa in Southern France given to Victor’s sister Princess Maria Letizia Bonaparte the Duchess of Aosta. Her fortune was split between her various family members. One of my favourite quotes about Eugenie’s life is courtesy of Lord Roseberry who wrote “To the surviving Sovereign of Napoleon’s dynasty, the Empress who had lived on the summits of splendour, sorrow and catastrophe, with supreme dignity and courage”. Tell me that life would not make a hell of a tv show. Honestly pretty much any part of her life could be covered; I do quite like the idea of show revolving around young Eugenie meeting Napoleon and becoming his Empress however the middle portion of her life (circa 1860 to 1880) was full of politics and would made an excellent series. Even her post Empire life and widowhood was interesting. In an ideal world HBO would give me the funds to create a three maybe four part series covering those three different eras of her life; I mean the fashion and sets would be stunning, the political shenanigans amazing and the drama never-ending. She lived for nearly a century and witnessed the establishment of two empires (The French Second Empire and the German Empire), the fall of several empires (The French Second Empire, The Austrian Empire, The German Empire, The Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire), a world war and the deeply changing social and political landscape of the early 20th century. The woman lived I tell you. How incredible a series could you make from all that?!

It’s very rare for me to include women on this blog that lived into the 20th century however this woman right here is so interesting to me and I’m always disappointed in how few people in the UK know about her. I mean she was known as both the “Joan of Arc of the Arabs” and “The Sword of Damascus” and potentially holds the world record for greatest number of times sent into exile, which just all makes her sound SO cool. Nazik Al-Abid was born Nazik Khatim Al ʿAbid Bayhum in 1887 into an influential family in Damascus; her father Mustafa al-Abid, was an aristocrat who held various political positions; he was at one point charged with administrative affairs in Kirk and was also an envoy to Mosul under the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II. Her uncle Ahmad Izza al-Abid was an influential judge who acted as a close advisor to the Sultan. She was raised predominantly in Istanbul and was given an exemplary education in various Turkish, American and French schools; her education culminated in her graduating with a BA in architecture from the Women’s College in Istanbul (I would like to emphasise this fact to those who think Islamic societies are inherently backwards and have always been far behind Europe in being socially progressive; the first woman to achieve a degree in the British Empire was Grace Annie Lockhart in 1875 so not that many years before Nazik graduated with her degree). In 1908 following the Young Turk Revolution and the deposition of Abdulhamid II, her family were exiled back to Damascus for ten years (that’s exile numero uno). Nazik soon became an advocate for women’s suffrage and a fierce opponent of the Ottoman occupation of Syria; she criticised among other things the exclusion of Arabs from senior government offices and the increasing militarisation of the empire. In 1914 she established a group to advocate for women’s rights and frequently wrote on the topic of women’s rights, often writing under a male pseudonym for various newspapers; her group came under intense scrutiny from the Ottoman military governor of Damascus who suspected that the organisation was closely and secretly connected to the Syrian nationalist underground movement. Nazik’s continued activism and refusal to back down meant she was in a perilous position and her life was in very real danger; she ended up getting into very hot water with the Ottoman government leading to her being forced into exile in Cairo (that’s exile number 2). Clearly the Ottoman authorities wanted her as far away from Istanbul as possible. In 1918 following the collapse of Ottoman Empire, she and her family returned to Damascus; she continued her activism and was particularly prominent during the 1919 Syrian’s women movement. That same year she founded the Nur al-Fayha’ (Light of Damascus) society and magazine. Some of the quotes about Nazik from this time are so amazing; her cousin was quoted as saying of her “[She was] very liberal with a strong character. She was a true rebel” whilst one Syrian government official very rudely said “God created her with a half a mind, how can we give her the right of political decision-making?”. Although fiercely unpopular amongst the upper echelons of Syrian society, particularly members of the Syrian government who HATED her, she was beloved by the people who considered her a hero. In 1919 she led the head of the women’s delegation at the King-Crane commission; her delegation’s role was to represent Syria’s response to the idea of a French Mandate in the aftermath of the downfall of the Ottoman Empire. Present at the commission was a number of foreign dignitaries including the US President Woodrow Wilson who granted her a personal meeting, during which she controversially removed her hijab symbolising her desire for a secular and liberal Syria (the American’s can I point out were very impressed by her and it’s clear from the writings of one American ambassador that he may or may not have developed a little bit of a crush). To say she pissed off the Syrian authorities is an understatement.

In 1919 and 1920 she was a driving force behind a law that would grant women suffrage; had the law passed, Nazik and her fellow Syrian women would have gained suffrage before American women. The conservative members of the Syrian parliament however were determined to see the law fail and did everything they could to obstruct the passing of the law. In 1920 however the French mandate was declared and women’s suffrage had to take a back seat. Determined to play a role in the incoming fighting between Syria and France, she co-founded the Red Star Association (a bit like the Red Cross) and was awarded the rank of “honorary president” of the Syrian Army by King Faysal. She led Red Star nurses in the Syrian Army’s battle against French forces during the Battle of Mayasalun in July 1920; she’s considered the first female general in Syrian history and her appointment caused even more controversy. This woman attracted controversy like no-one else I’m telling you. The Syrian forces were unsurprisingly dwarfed by the brutal and vast French army; to prevent blood-shed, the Syrian king, surrendered. His minister of defense, however, was very unimpressed and in a scheme that can only be described as “if we’re going to die, we’re going to die, fighting”, decided to scrape together a load of decrepit weaponry and volunteers for what was, let’s be honest, a suicide mission. France had over 9,000 well-armed troops. Syria had 1,500 untrained conscripts. The odds were not in the Syrian’s favour. One of the volunteers was none other than our girl right here Nazik. The image of her in military attire with a rifle on her shoulder, devoid of her hijab caused absolute pandemonium amongst conservatives and the image appeared on the front of every newspaper in the Middle East. To calm tensions, she reverted to wearing a less restrictive veil although that did little to ease the scandal. She was given the nickname “The Sword of Damascus” which I think is actually very cool; her critics accused of all sorts including blasphemy and blasted her decision to fight in war. Fighting was considered by conservatives a man’s duty, not a woman’s; she seemed somewhat amused by the reaction. The Syrian forces were unsuccessful and the French promptly exiled her once again, the minute they took control of Syria (for those still counting that’s exile number 3); this time she was exiled to Jordan. She however was immensely popular in Syria and the common people were the ones to hail her as “Joan of Arc of the Arabs” as well as “The Sword of Damascus”. Under immense pressure from the public, the French authorities granted her amnesty and allowed her to re-enter Syria on the condition that she avoid all politics. Did she listen? Nope she did not and just a year later they threatened to arrest her when she founded a girls school which was viewed as competition for resources with French humanitarian agencies and programs; this pissed off various French politicians and she was exiled AGAIN (exile number 4 people). The French clearly hadn’t quite learned their lesson because they allowed her to return, once more on the condition that she behaved herself. Somewhat predictably, she didn’t. In 1924 she founded the Women’s Union alongside Adila Bayhum and Labiba Thabet and a year later in 1925 the Syrian Revolt against French rule took place, once again throwing Nazik back into the limelight. She dedicated her time to smuggling food and munitions to anti-French rebels, nursing the wounded and continuing her political activism; she set up yet another organisation which provided outreach to displaced women and those who had been widowed/orphaned in the war. Eventually the French had enough, and issued an arrest warrant, causing her to flee to Lebanon (this I think counts as exile number 5, even if they didn’t officially exile her. They would have had they been able to arrest her). Whilst in Lebanon, she met Muhammad Jamil Bayhum a Lebanese intellectual and politician; the two married soon after meeting – he was very supportive of her political activism which she continued even in exile. In 1928 because the French are clearly masochists they pardoned her and allowed her to return to Syria. Jesus Christ, do they not learn. She was determined to continue campaigning for political change and in 1933 she founded the Niqâbat al-Mar’a al-‘Amila or The Working Women’s Society, working on the issues that affected all Syrian women in particular women’s economic empowerment and working’s rights including maternity leave (this is amazing when you consider the fact that so-called progressive countries such as the US do not in the year 2023 have a law which makes it obligatory for US employers to give paid maternity or parental leave to their workers).

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, she remained the countries most prominent female political activist; alongside her very supportive husband she financed and supported a book called Veiling and Unveiling and financed the construction of a hospital – she sat on the board of directors of said hospital until her death. At this point the French were tired of exiling her and there were no more attempts at exile or arrest. In 1945 her greatest dream came true when Syria gained de jure independence as a democratic parliamentary republic with the Republic of Syria being proclaimed in October of that year (although French troops did not leave until 1946). In 1948 during the Arab-Israeli War, she established an organisation to assist Palestinian refugees. Five years later in 1953 the women of Syria received the right to vote and with that Nazik’s two greatest dreams – Syrian independence and women’s suffrage were complete. In the years afterwards it became more socially acceptable for women to remove their hijabs as Nazik had done all the way back in the early 1920’s when she’d managed to cause an international scandal by doing so. By 1960 a woman had been elected to parliament. All this had been possible in part due to Nazik and her seemingly boundless determination to make Syria a free nation and it’s women, equal citizens. By the time she died in 1959 at the age of 72, she had achieved almost everything she had wanted to. God this woman’s life was absolutely amazing and 100% deserves a series. The thing is her entire life was dramatic so there’s a lot to fit in; there’s also the fact she lived a long life so it’s difficult to narrow down a specific period to focus on. If it were up to me I’d try to do a series that encompassed most of her life; it would probably start with her graduation and the subsequent Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and end with women receiving the right to vote in 1953. It’d have to be made up of a few seasons; I just think it would be such an interesting take on Middle Eastern politics in the 20th century. It would also be vital that the role was played by an Arab actress, preferably a Syrian one. I can’t imagine Nazik would want to be portrayed by anyone else.

The first time Blanche of Castile pops up in the historical record as a person of importance was in the late 1190’s when the Castilian court received a visit from the living legend that was Eleanor of Aquitaine. Now why you may ask was Eleanor visiting the Castilian court when she had a whole hosts of shenanigans in France and England to deal with? Well her daughter (& namesake) Eleanor was the Queen of Castile as the wife of Alfonso VIII (and therefore Blanche’s mama) so she decided to pay her daughter and grandchildren a lil visit. Except in true Eleanor of Aquitaine fashion, her visit was not completely devoid of politics. You see her son John King of England was on the cusp of signing a peace treaty with Philip Augustus King of France (son of Eleanor’s ex-husband & half-brother of two of her daughters); one of the stipulations of the peace treaty was that Philip’s son Louis would marry one of John’s nieces. Philip and John, trusting that Eleanor knew best, asked Eleanor to decide which of John’s Castilian nieces was the best choice. Thus Eleanor travelled to Castile to decide the next Queen of France. In the run up to this visit, everyone had settled on the very beautiful Urraca as the obvious choice and she was basically being prepared for queenship; upon her arrival however Eleanor declared that although Urraca was the most beautiful of the Castilian princesses , the younger princess Blanche had the better personality and possessed the temperament to be Queen. Because a) everyone collectively knew disobeying Eleanor was a questionable decision and b) no-one knew better than Eleanor what being Queen of France entailed (remember she’d been queen of France in her youth when she’d been married to Philip Augustus’ father Louis), everyone wisely listened to her. Thus the Treaty of Le Goulet was signed with Blanche and Prince Louis’ becoming engaged. In the spring of 1200, Eleanor took it upon herself to cross the Pyrenees Mountains (despite being nearly 80) with her 12-year-old granddaughter, presenting their next queen to the French. On 22 May 1200, the marriage treaty was finally signed and the next day at Port-Mort on the right bank of the Seine a lavish wedding took place with Eleanor at the helm (the wedding had to take place in Blanche’s uncle John’s lands rather than the lands of her new father in law because Philip Augustus was under interdict after a quarrel with the Catholic Church). Blanche was twelve years of age, and Louis only 13, so the marriage was not consummated until a few years later (this is where I emphasise that 12-year-olds marrying and immediately consummating their marriage was NOT NORMAL, and I beg the people that say that in the Medieval/Tudor era it was a regular thing, to find examples beyond Margaret Beaufort. Margaret’s case was highly unusual, it was not the norm and even Margaret’s contemporaries were shocked that she’d survived childbirth, so much so that, Bishop Fisher commented on it, in her eulogy decades later. If they knew it was messed up and questionable in the 1400’s, then they definitely did in the late 1190’s-early 1200’s). Now upon consummating the marriage Blanche got pregnant quickly, like speedy-gonzalez quickly and she gave birth to her first child a daughter also named Blanche in 1205. The first few years of her political career was based heavily around child-bearing; three children followed the birth of their daughter Blanche; a son Philip in 1209 (he died a decade later) and twins John and Alphonse who were born in 1213 and died within hours of their birth. Their first child to survive to adulthood was their son Louis (REMEMBER HIM) who was born in 1214. Seven sons (Robert, Philip, John, Alphonse, Philip-Dagobert, Etienne & Charles) followed as did another daughter Isabelle. Altogether she would end up giving birth to thirteen children between 1205 and 1227. In 1215-1216 her uncle John ran into a spot of bother with his barons who decided to offer Louis the English throne; the basis for their offer was that Blanche as the granddaughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine possessed English blood. Louis and Blanche genuinely considered the offer, however it was rescinded in October 1216 when the ever-problematic John died and the notoriously fickle barons transferred their allegiance to John’s nine-year-old son Henry (who became Henry III). Louis did not like that and decided to continue claiming the English throne in the name of his wife. The French however were like “absolutely not, terrible idea” and Philip Augustus, not exactly England’s biggest fan refused to help his son. Blanche however proved that she had learnt something from her grandmother and decided to back her husband to the hilt; she raised money from her father in law by threatening to put her children as hostages. After French forces were defeated at Lincoln in May 1217, she used that money to fund reinforcements including two fleets that sailed to join Louis in England. Louis and Blanche were unsuccessful and the English fleet completely destroyed the French fleet. What they did accomplish, was that now everyone knew that Blanche was that girl.

Her father in law died in July 1223, leaving Louis (now Louis VIII) and Blanche as King and Queen of France. The thing is Louis didn’t actually last that long. He died just three years later in 1226, leaving their 12-year-old son as King. Louis’ death was super bad timing; his southern barons were still causing a ruckus and the situation was pretty critical. Per Louis’ will, Blanche, by then 38, was declared regent and guardian of their children. She was thus now fully in control of France; her first port of call was to have their son crowned at Reims – forcing the somewhat reluctant barons to swear allegiance in the process. She then released a couple of her father in law and husband’s old prisoners including Ferdinand Count of Flanders – she also ceded land and castles to Philip I Count of Boulogne. Some very important barons refused to recognise the new king and at one point tried to abduct Blanche and Louis; she appealed to the people of Paris who lined the roads and protected them. She then forged a somewhat unexpected alliance with Theobald IV of Champagne; he had engaged in quite the conflict with her late husband and Blanche had actually barred him from her son’s coronation, leading to him initially leading a conspiracy with Hugh X Luisgnan and Peter I of Brittany against the crown. After meeting Blanche however he seemed to change his mind and the two formed a close partnership with him helping her to raise an army which she would use on a number of occasions to defend her son’s interests. I’d like to point out that he and Blanche were technically cousins; she was Eleanor of Aquitaine’s granddaughter whilst Theobald was Eleanor’s great-grandson. Rumours then began (surprising, surprise) that Theobald and Blanche were having an affair; Theobald did not help matters by composing poetry for her. The rumoured affair was commented on by both Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris; one story that emerged was that Theobald had murdered Blanche’s husband and then began a relationship with her incurring the wrath of her son who as a young man allegedly challenged Theobald to a duel to avenge his father’s death. Blanche according to the stories stopped the duel. Is it possible they had an affair? I suppose so. There however is no evidence to back it up, and the truth is, a lot of the barons were pissed at Blanche being in charge and resentful of Theobald’s powerful position at court (the Count of Champagne had emerged from the Succession War with a lot of influence) so spreading fabricated rumours of an illicit affair was a pretty good way of damaging both Theobald and Blanche’s reputations. She would serve as regent from 1226 to 1234 and again when her son went on crusade between 1248 and 1252 (what is it with 12th and 13th century men and their obsession with crusade?); she was a superb regent and became known by her enemies as “Dame Hersent” (the wolf in the Roman de Renart). She spent her regency dealing with the annoying barons; in January 1229 she led her forces against Mauclerc and forced him to recognize the king whilst that same year she was responsible for the Treaty of Toulouse in which Raymond VII Count of Toulouse (another grandchild of Eleanor) submitted to her son. This brought an end to the Albigensian Crusade. The barons were not her only concern; she also had to deal with Henry III of England (another grandchild of Eleanor); in the later 1220’s she blocked his every attempt to marry a French bride – he first asked for the hand of Yolande of Brittany then Joan Countess of Ponthieu. She blocked both matches by a) arranging for Yolande to marry her son John and b) convincing the pope to deny Henry a dispensation on the grounds of consanguinity. Henry understandably felt a little miffed about the situation and in 1230 tried to invade France. Blanche managed to stop Henry’s mother Isabella the Countess of Angouleme and her husband Hugh X of Luisngnan from supporting the English (although she had to give up some of the crown’s influence in Poitou) however was less successful with Mauclerc and the Duke of Brittany who did support Henry. To top off Blanche’s very terrible day, her troops became insubordinate and refused to serve beyond the 40 day feudal contract; the Count of Boulogne left the royal forces and decided to tear through Champagne. Henry it turned out was not the greatest of military leaders and squandered the odds which let’s be honest were very much in his favour. Some of the lords in Poitou remained loyal to Louis and Blanche and Henry was not willing to commit to a large military offensive, instead deciding to return to Brittany. Seeing off an invasion did wonders for Blanche and Louis’ reputaton and their rule was seen as pretty stable. Louis realised that he basically owned his crown and realm to his mama and remained pretty much under her influence for most of her life. Louis began to become more involved in politics in the early 1230’s and the regency came to an end in 1234; despite this Blanche remained super powerful and it was well known that her son did not withhold anything from her. There was also a pretty big rule at court which was that no-one was allowed to speak against the queen mother. It was Blanche that arranged the marriage between her son and Margaret of Provence the eldest of the four daughters of Ramon Count of Provence and Beatrice of Savoy. That backfired on her slightly – Margaret and Blanche did not have a good relationship, in part due to the fact that they both wanted to be numero uno in Louis’ life and Margaret somewhat understandably resented the influence her mother in law had on her son – especially as Blanche was a bit of a nightmare mother in law (it’s believed she tried to limit the amount of time Louis and Margaret spent together). There was also the fact that the two women were constantly compared to one another – Blanche had always been considered the beauty of the court despite her age. That changed with the arrival of Margaret who quickly became the centre of court.

One of the ongoing issues of 1200’s Europe, particularly in France, was the massive anti-semitism that was prevalent throughout society; Louis insisted on the burning of the Talmud and other Jewish literature however Blanche intervened and promised Yechiel of Paris (basically the spokesman for the French Jewish community) that he was under her protection. She then insisted on a fair hearing for them; she herself presided over the formal disputation of court. In 1248 her son decided to go on crusade (of course), a course of action she was strongly opposed to. He decided to go anyway, and left her once again as regent. In his absence she managed to maintain peace whilst also draining the country of men and money to aid her son’s ludicrous shenanigans in the East. In November 1252 she suddenly fell ill and died within a few days; she was buried at the Maubuisson Abbey which she had founded herself. Because 13th century international post was not exactly stellar, Louis did not hear of her death until the following spring and was HEARTBROKEN; he allegedly didn’t speak to anyone for two days afterwards. Blanche is now considered to be one of the most influential women in French history. I love her. She’s so fascinating and I would kill for a tv show of her. It’s always surprising to me that’s she’s not as well known as other French consorts including her grandma and Catherine de Medici; I mean her son literally went on to become a Saint. Like with a lot of other women in this Dear Hollywood posts, a tv show could cover a whole host of periods of her life. I love the idea of tv show of her life beginning with her grandma Eleanor choosing her as the next Queen of France and travelling together over the Pyrenees. In a previous Dear Hollywood post (see here) I included Eleanor and put forth the idea of a show that included their travels. You could have Eleanor giving Blanche a lesson in how to be Queen and then show Blanche taking those lessons forward. To cover her full life you would need a pretty significant number of seasons, although alternatively if you wanted something shorter, the show could focus solely on her regency which is probably the most important part of her life.

There are few women of the 20th century that have a worse reputation than this woman right here. Cixi was born Yehe Nara Xingzhen on the 29th November 1835 in Beijing; the daughter of Huizheng a man who held the title of a third class duke and his wife Lady Fuca of the Manchu Yehe Nara clan. Very little is known about her childhood other than the fact she was raised alongside her brother Guixiang and a sister Wanzhen – its likely Cixi was the eldest of the three children. It’ also believed her father died at some point in her childhood; he was certainly dead by 1851 when at the age of 15 she was chosen to participate in a bride show for the Xianfeng Emperor alongside sixty other candidates all vying to be his wife. Several candidates were chosen including Cixi, Li of the Tatara Clan and Zhen of the Niohuru clan. She entered the Forbidden City on the 26th June 1852 and was placed in sixth in the Emperor’s ranking of consorts, being given the title “Noble Lady Lan”. She was promoted in February 1854 to the fifth rank and granted the title of “Concubine Yi”. A year later she became pregnant; the birth of her son Zaichun the Emperor’s first and only surviving son in April 1856 won her yet another promotion, this time to the third rank. She was given the new title of “Noble Consort Yi”. Upon her son’s birthday she was promoted yet again, meaning she was now second in the Emperors list of consorts with only the Empress Niohuru ahead of her (despite being basically married to the same man the Empress and Cixi seem to have been actually quite close). The thing is Cixi very much stood out in the harem; unlike the majority of other Manchu women, she had clearly been given a thorough education and she was known for her ability to read and write Chinese. The Emperor was clearly quite impressed and he began to rely on her intelligence and skill; the Emperor it should be noted had deteriorating health despite only being in his 20’s and she began helping him in the governing of the Chinese state on a daily basis. He was known to frequently have Cixi read palace memorials for him and leave instructions on the memorials according to his will. This meant that a) Cixi found herself in very close proximity to the apex of power, b) was aware of every aspect of the state’s affairs and c) learnt all about the art of governing from the emperor. In September 1860 towards the end of the Second Opium Warr, the British envoy Harry Parkes and a number of other British diplomats were arrested, tortured and executed, which to put it mildly colossally pissed off the British who in retaliation banded together with French troops to attack Beijing. The Emperor and his entourage including Cixi and their son fled the city leaving the Old Summer Palace which was destroyed by the British and French. The Emperor fell into a deep depression at the news which combined with his already ailing health was a recipe for disaster. He allegedly turned to alcohol and drugs and was soon pretty much on the cusp of death. In the summer of 1861 he summoned eight of his top ministers and named them the “Eight Regent Ministers” who would rule on behalf of his son & heir who was only 5 years old. That little boy happened to be the son of none other than Cixi herself. Cixi was allegedly given a seal by the Emperor on his deathbed as did his empress; it was assumed at the time and by historians since that the seals were granted to the two women with the hope that they would work together to help the young emperor rule and act as a check on the power of the regents. This to be quite honestly seems unlikely – the seals were informal – they lacked actual authority and were considered objects of art rather than actual instruments of state. If the Emperor wanted the Empress or Cixi to act as regents, he could have named them as such in his will however he did not. The seal in all likelihood was just a gift from a dying man to the mother of his son and heir. With his death, his Empress became Empress Dowager Ci’an whilst Cixi was elevated to Empress Dowager Cixi; they were also known as the East Empress Dowager and the West Empress Dowager (this was because Ci’an took up residence in the eastern Zhongcui Palace whilst Cixi moved to the western Chuxiu Palace. Cixi (a shrewd political strategist in her own right) was not exactly thrilled at eight regents ruling on behalf of her son; especially as she wasn’t highly fond of the regents in question. Despite being the mother of the new Emperor she had no intrinsic political power and the youth of her son meant he had no political power either. This meant she was forced to ally herself with other political figures unhappy with the new regime; this included the other Empress Dowager Ci’an. The two women joined together along with. a number of other court officials and imperial relatives with the plan that they would become co-reigning empress dowagers with more authority invested in them than the eight regents (as I previously mentioned Cixi and Ci’an had actually been pretty close friends since Cixi’s arrival in 1852). The imperial court soon became extremely factionalised and full of conflict; the two Empresses clashed spectacularly with the eight regents particularly the leader of the pack Sushun who did not appreciate Cixi and Ci’an’s interference in the affairs of state. Ci’an herself grew tired of the conflict and the non-stop arguments Cixi seemed to get into with the regents; eventually she started ditching court appearances leaving Cixi to deal with them alone. Cixi seemed to come to the conclusion that she needed to build her own political faction; the thing is the eight regents had made a lot of enemies and those enemies including Cixi’s brother in laws Prince Gong and Prince Chun flocked to Cixi’s side. This was against all precedent; Qing imperial tradition dictated that women and princes were not allowed to engage in politics, yet here they were a woman and two men planning a political coup. Now despite the fact it had been a number of months since the Emperor’s death, the court had still not returned to Beijing; this was because they were waiting for an astrologically favourable time to transport the emperor’s coffin back to the city. This gave Cixi time to plan a coup, and when the funeral procession did eventually leave for Beijing, Cixi made the decision to return with her son before the rest of the procession along with Zaiyuan and Duanhua, two of the eight regents whilst the main regent Sushun was left to accompany the late Emperor’s coffin. This was vital as Zaiyuan and Duanhua were Sushun’s closest allies. Separating them was vital to Cixi’s coup succeeding. Upon arriving in Beijing, Cixi accused the regents of having carried out incompetent negotiations with the “barbarians” (aka the British) – those negotiations she claimed had caused the Xianfeng Emperor to flee to Rehe Province “greatly against his will”, basically implying that they were responsible for his death. She then received an official edict from the highly important Shandong region which requested that she become de-facto ruler and “rule from behind the curtains” with Prince Gong as an executive advisor to the new Regent and child-Emperor. When the Regents were arrested, Prince Gong suggested that the regents should be executed by slow slicing (“death by a thousand cuts”) aka the most painful method of execution possible. Cixi, trying to demonstrate that she was the grown up in the room, capable of exceptional justice, fairness and mercy, declined the suggestion and ordered that only Sushun and his minions Zaiyuan and Duanhua be executed whilst the other five regents were merely exiled. Sushun was beheaded whilst Zaiyuan and Duanhua were forced to hang themselves. In another break from tradition and once again in an attempt to portray herself as being kind and merciful, Cixi outright refused to execute the families of the three men (Qing imperial tradition dictated that if traitors were executed than their families should be too).