Recently I did an instagram post (see here) about Anne of Brittany who was twice the Queen of France as the wife of Charles VIII and Louis XII; I also did a post mere days before about Emma of Normandy who was twice the Queen of England as the wife of both Aethelred the Unready and Cnut. It got me thinking about the prevalence of women married to multiple kings and crowned multiple times and the complications and difficulties that come with it, especially in regards to someone like Emma of Normandy who had sons from both marriages and had to navigate the ever-complex nature of succession. In Emma’s case she first backed her son from her second marriage before securing the throne for her sons from her first marriage, over her step-son. Being a queen/wife of a king, particularly in the Medieval or the Early Modern period is no walk in the park. Being the queen/wife of two kings, particularly if one succeeds the other, is even more complex!! Now this post is dedicated solely to women crowned Queen of the same nation twice; there are many women who were married to a king, widowed and then forced to marry the king of another kingdom (Eleanor of Austria for example was first married to the King of Portugal and then the King of France whilst Eleanor of Aquitaine (ICON) was married first to the King of France and then the King of England etc). There are far fewer women who are Queens of one kingdom, but the wife of multiple kings.

The inspiration for this post was Anne of Brittany so it’s only fair she be first on my list!! Now Anne was born in Nantes in 1477 the daughter of Francis II Duke of Brittany and Margaret of Foix Infanta of Navarre. Her childhood was a pretty depressing one; her mother died when she was 9, her father died when she was 11 and her sister Isabeau died when she was 13. Now as the eldest daughter of a ruling duke, she received a pretty thorough education and read/wrote French and Latin; claims she was also taught Greek and Hebrew are unproven. It’s also fairly unlikely she spoke the Breton language. Anne by all accounts was a babe – reports from her youth describe her as young, pretty and rosy checked. At the time Brittany differed from many other states in Europe because there was no strict line of succession (unlike the rest of France) however following the Breton War of Succession a century earlier, the duchy had been acting under an unofficial semi-Salic succession law which meant that women could inherit IF there were no male heirs. Anne had no brothers and so in 1486 when she was 9, her father recognised her as his heir. Choosing a future husband for her thus became his top priority. There were a number of negotiations for her to marry a significant number of suitors including Edward the Prince of Wales (son of Edward IV & Elizabeth Woodville) and Henry Tudor (later Henry VII King of England) although the negotiations for the latter never got very far. In 1488 her father was defeated by the French King in battle and forced to sign the Treaty of Sable which was embarrassing to say the least. He died shortly afterwards and on his deathbed he allegedly made her swear she would never allow France to control Brittany. A pretty big task to give a 13-year-old with no political experience. She was crowned Duchess of Brittany in February 1489 and over a year later in 1490 she was married by proxy to Maximilian I of Austria, a widower 18-years her senior. She thus became Queen of the Romans (nice gig if you can get it). The French were to put it mildly very unimpressed at the marriage; not only did it violate the Treaty of Sablé (the King of France having not consented to the marriage), but Maximilian was also a fierce enemy of France (to be honest Maximilian was an enemy of almost everyone). The French army then descended on Brittany and in the Spring of 1491 the King of France Charles VIII lay siege to Rennes, where Anne was based. After Charles VIII entered the city both parties signed the Treaty of Rennes. Days later Anne became engaged to the King and then travelled with her own army to Langeais to be married. Austria made diplomatic protests (including to the Vatican), claiming that the marriage was illegal for three reasons a) the bride was unwilling, b) she was already legally married to Maximilian and c) Charles VIII was legally betrothed to Maximilian’s daughter Margaret. The marriage between Charles and Anne took place on 6th December; the wedding was arranged by Charles’ ICONIC sister and regent Anne de Beaujeu (who had been ruling France in her brother’s name since 1483 and was a bona fide legend) and was done discreetly and quickly. In February 1492 the marriage became legal when Pope Innocent VIII annulled her marriage to Maximilian and validated her union with Charles. Anne reluctantly agreed to the terms of the marriage contract which stipulated that the spouse who outlived the other would retain possession of Brittany and that if Charles VIII died without male heirs, Anne would marry his successor. Anne and Charles would end up being married for seven years until his death in 1498. Although the King and Queen often lived apart, she was pregnant for most of her married life (with a child every fourteen months on average); their six children however were all stillborn or died in infancy. In the years after their marriage Anne had a very limited political role; whenever her husband was away he entrusted the governance of France to his sister Anne of Beaujeu who despite no longer being regent, was still easily one of the most powerful women in Europe. When Charles died in 1498, Anne was 21 and childless. She then finally took personal control of the administration of the Duchy of Brittany and proved herself to be a shrewd, proud and intelligent ruler, basically everything the people of Brittany wanted. She also surrounded herself with a close circle of poets, artists and musicians, becoming a highly sought after patron of the arts. Shortly after her husband’s death, the terms of her marriage contract came into force meaning she had to marry Charles’ successor, his cousin Louis XII however he was awkwardly already married to Charles’ sister Joan; I cannot even begin to imagine family reunions. Anne agreed to marry Louis XII as long as he obtained an annulment from Joan within a year. Anne then returned to Brittany. I tend to be of the belief that Anne hoped the Vatican would refuse to grant Louis an annulment however because men in the 15-16th century were as a whole generally disappointing and fairly unreliable, the Pope Alexander VI (of the House of Borgia infamy) happily granted the annulment and Anne and Louis were married in January 1499. Anne made it clear that she wished to exercise her rights as sovereign Duchess from that point forward. She also made sure that their marriage contract stipulated that, since Anne personally retained rights to the duchy, the couple’s second child would be Anne’s own heir. This was meant to keep France and Brittany separate (spoiler alert; her plan failed miserably). During their marriage Anne is recorded as being pregnant five times although only two daughters Claude and Renée survived to adulthood. She was a devoted mother and spent as much time as she possibly could with her daughters. Her fierce defence of Brittany would prove to be in vain; whilst she arranged the marriage of their eldest daughter & heir Claude to Charles of Austria (later Charles V Holy Roman Emperor), her husband secretly arranged for Claude to marry his cousin & the heir to the French throne Francis of Angouleme. Anne, who I can only imagine was very unhappy, refused to agree to the marriage and after Louis signed a contract making the engagement legal, Anne left him (TEAM ANNE) and went on a long tour of Brittany. Amusingly it was noted by observers during her road-trip around Brittany that Louis was particularly devastated by her absence and in one letter from Francis of Angouleme’s mother (and Anne’s arch-rival) Louise of Savoy to Michelle de Saubonne, she wrote that Louis “is as wretched as can be without her.” Serves him right for scheming behind her back!! Eventually she gave in and returned to him; I suppose she couldn’t travel around Brittany forever. In 1514 after suffering a kidney-stone attack, Anne conferred the succession of Brittany to her second daughter Renée. She died shortly thereafter. Louis decided to disappoint his wife one final time (at least he’s consistent) and ignored her dying wish, confirming Claude as the new Duchess of Brittany. In 1515 Claude married Francis and later that year Louis died, leaving Francis and Claude the new King and Queen of France. This meant that Brittany once again became the property of France, the one thing Anne had spent her life trying to avoid. Her body was later buried in an extravagant tomb alongside Louis’ in the Saint Denis Basilica whilst her heart was returned to her beloved duchy where it was placed in her parent’s tomb.

One thing that does occasionally tend to irritate me, is that very little of English history prior to the Norman Conquest is as well known as it should be. Yes the names Edward the Confessor and Alfred the Great, probably ring a bell for many people but a large swath of England probably wouldn’t be able to tell you who those fellas actually were. In the pre-Norman period there was one woman that stood above all the rest. Meet Emma of Normandy. Emma was born circa 984 the daughter of Richard I Duke of Normandy and his long-term mistress turned wife Gunnor who we’re fairly certain was Danish although her exact parentage is unknown. Very little is known about Emma’s childhood; the first time she became a person of prominence was in 1002 when she was married to Aethelred II King of the English. He was 28 years her senior and had 10 children from his first marriage – the marriage took place to ease tensions between England and Normandy (and by tensions I mean her new husband had tried to kidnap her brother). As his wife, Emma was given a new Anglo-Saxon name (although she’s remembered by her birth name) and granted a number of properties and estates in Winchester, Devonshire, Suffolk and Oxfordshire. Together Emma and Aethelred had three children, two sons Edward (later known as Edward the Confessor) & Alfred and a daughter Goda. In 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard the King of Denmark invaded England and Emma fled with her children to Normandy where they remained for a year (at some point her husband joined them) before returning to England upon Sweyn’s death. That same year her husband’s eldest son & heir Aethelstan died and Emma sought to have her son Edward named heir despite the fact that her husband had a number of other older sons from his first marriage. Despite support from some of Aethelred’s advisors & nobles, she was opposed by her other step-son Edmund. During her time as Aethelred’s wife she’s recorded as witnessing various charters suggesting she had some influence but nothing particularly remarkable. In 1015 Sweyn Forkbeard’s equally as formidable son Cnut began to complete his father’s conquering of England; now at this point Aethelred was basically on death’s door and thus unable to really do anything remotely kingly. Responsibility for England fell to Emma who managed to hold Cnut back from entering London. Aethelred’s death in 1016 threw a bit of a spanner in the works because now Edmund was King. And Edmund was just not great. Certainly not as intelligent or politically shrewd as Emma who continued to maintain control of London and hold Cnut back. Then Edmund died in November and Emma really couldn’t carry on holding Cnut back forever. Cnut then entered London and what happened next is not 100% clear. What we do know is that Cnut and Emma shocked everyone by marrying; what we don’t know is in what circumstances. Some chroniclers seem to suggest that Emma was essentially prisoner and thus forced into the marriage; in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle it’s written that “before the Kalends of August, the king commanded the relict of king Æthelred, Richard’s daughter, to be fetched for his wife; that was Ælfgive in English, Emma in French”. Other chroniclers however suggested the two engaged in a series of negotiations which culminated in their marriage. Now Emma’s motives for marrying Cnut are super interesting and complex, and there’s really no agreement among historians. One of her leading motives I would think would have been the protection of her sons; undoubtedly Cnut would have been threatened by her still-underage boys, especially as they had taken refuge at the court of their uncle in Normandy. Princes with a claim to the throne can be extremely dangerous if not kept under control and as England did not follow the rule of primogeniture yet, there was no reason why either boy could not claim the throne. By marrying Cnut, Emma managed to keep her sons alive whilst Cnut either executed or exiled the heirs to the throne (not born to her) including her step-son Eadwig and Edmund’s young sons. In the Enconium, it’s suggested that Emma was also concerned about sons she and Cnut might have with it written that “she refused ever to become the bride of Cnut, unless he would affirm to her by oath that he would never set up the son of any wife other than herself to rule after him, if it happened that God should give her a son by him”. Although Emma and Cnut’s marriage was a political strategy, it became a loving and seemingly happy marriage and the two had a son Harthacnut and a daughter Gunhilda. Through her marriage to Cnut, Emma was Queen of England, Queen of Denmark and Queen of Norway; she was a very prominent and politically involved Queen who held significant power, more so than she’d had when married to Aethelred. Cnut frequently left England to attend to his other territories and it’s widely believed she was left as regent in his absence. She was a significant patron of the church and appears alongside him on the frontispiece of the New Minster Liber Vitae; sources at the time describe her basically as being Cnut’s partner in power. On his death she was powerful enough to take hold of the royal treasury at Winchester, and was for a number of decades the richest woman in England. They were married between 1016 and 1035 when Cnut died; upon his death she chose their son Harthacut as the new king rather than her sons with Aethelred or Cnut’s sons from his first marriage. Her eldest son Edward never forgot that she’d chosen his half brother nor did he ever really seem to forgive her either. Now, Harthacnut was not immediately crowned; he was stuck in Denmark dealing with rebellion. Emma was designated as regent in his absence however Harold, Cnut’s son from his 1st marriage tried to claim the regency for himself. In 1036 Emma summoned her sons from her first marriage back to England which would prove to be a disastrous decision. Whilst in England one son Alfred was kidnapped and blinded, dying not long afterwards allegedly on Harold’s orders. Her other son Edward then returned to Normandy for his own safety. In the absence of Harthacnut, Harold was proclaimed King although in 1039 Harthacnut assembled a fleet to sail for England. After the death of Harold in 1040, Harthacut was crowned King and Emma was finally Mother of the King. A year later in 1031, with Harthacut’s health declining, Emma convinced him to invite her son Edward back to England. This juggling of sons is SO complicated. Clearly keen to ensure England remained ruled by one of her sons, Edward was named heir to the throne upon his return. Harthacnut died in 1042 and Edward was crowned a year later in 1043. Evidently there was some tension between Edward and Emma (as I said he never forgave her for choosing Harthacnut over him) as he bizarrely accused her of treason and deprived her of her lands and titles. He changed his mind soon afterwards and everything was restored to her. Although not as powerful as she had once been, Emma remained prominent until her death in 1052; she even at one held the keys to the treasury at Winchester. After her death she was then interred alongside Cnut and Harthacnut and their bones now lie in Winchester Cathedral. Interestingly enough fourteen years after her death, her son Edward died without an heir and there was a mad dash for the throne. In the midst of the chaos her grand-nephew William (aka William the Conqueror) invaded England and crowned himself. The House of Normandy would rule until 1135 when the Anarchy kicked off. At the end of the Anarchy Henry II emerged the victor (Henry was the great-great-great grandson of Emma’s brother Richard) and founded the House of Plantagenet, setting the stage for the eight hundred years of royal English shenanigans that have followed.

Margaret was born in 1350 the sole surviving child of Louis II Duke of Flanders and Margaret of Brabant. Being the only surviving child of her father, meant that she was raised as heir to the duchy of Flanders; now Flanders was not one of those states that was vehemently against female rulers – she after all was Margaret III. Despite this, it was better they believed if she had a husband who could guide her. And by guide her – I mean rule for her. In 1355 when she was a literal five-year-old she was married to Philip of Rouvres, who was the grandson of Odo IV Duke of Burgundy. Philip had a plethora of titles including Duke of Burgundy, Count of Artois and Count of Auvergne & Boulogne. By marrying Margaret he thus was also going to gain control of Flanders, Nevers, Rethel, Antwerp, Brabant and Limburg. Job well done really. Now Philip also had a rather interesting mother; Joanna I who was Countess of Auvergne in her own right and Queen of France by virtue of her second marriage to John II King of France. She had ruled Burgundy on Philip’s behalf ever since the death of her father in law in 1349. She died in 1360 and Philip took power for himself that year. Margaret and Philip’s marriage would be a very brief one – he died in 1361 either from the plague or a hunting accident, leaving 11-year-old Margaret a widow. Being a widow at any age is awful, becoming a widow at 11 just plain sucks. Margaret then found herself in a bit of a sticky situation; due to her age they had no children (in fact their marriage hadn’t even been consummated) and he had no immediate successors. His step-father however took the opportunity to claim Burgundy as a new territory of France, granting it to his own son Philip who became Duke of Burgundy. As heir presumptive to her father’s territories, she was a very hot commodity on the European marriage market and was courted by a number of eligible gentlemen including Edmund of Langley the son of Edward III King of England and her late husband’s successor aka his step-brother Philip the new Duke of Burgundy. Her father stalled for YEARS, and was determined to get the best (and most beneficial) marriage alliance possible. After years of tough neogiaiting, Louis II eventually gave his consent for Margaret to marry Philip. In return for her hand he received several lordships and a payment of 200,000 live tournois. The marriage appears to have been a pretty good one and there’s no record of Philip having any mistresses or illegitimate children, a rare win for a woman in medieval European royalty. This marriage was most definitely consummated because the two went on to have nine children, only two of which died in infancy. Philip and Margaret arranged very advantageous marriages for all the children that did survive to adulthood; one of their sons John (later known as John the Fearless) was Duke of Burgundy whilst another son Antoine was duke of Brabant, their youngest son Philip was Count of Nevers and Rethel and their daughters Marguerite, Catherine and Mary became a Countess of Holland and Duchesses of Bavaria, Austria & Savoy respectively. Two of their sons would later die at Agincourt against the English. Her husband would play an incredibly important role in French government from the death of his brother Charles V in 1380; his nephew Charles VI was only 11 and so a council of regents was set up to govern France. The council was made up of his four uncles Louis Duke of Anjou, John Duke of Berry, Philip himself and Louis Duke of Bourbon. Philip was the most dominant of the four regents (Louis of Anjou had a claim to the Kingdom of Naples and so was preoccupied with various Italian shenanigans, John of Berry was only really interested in the Languedoc and Louis of Bourbon was unlike the others, not the son of a king and thus less relevant, not to mention potentially mental unstable). Margaret’s involvement in the regency is unknown but due to the strength of their marriage it’s likely she acted as her husband’s advisor. She certainly appeared to be very much in his corner. As the wife of one of the regent’s (and as the King was only a child with no living mother nor wife) Margaret was one of the highest ranked women in France. Her place as a Countess in her own right gave her further prestige. In 1384 her father died and Margaret inherited his territories. Despite their marriage, she was able to retain some independence from Burgundy, and most of her political involvement was in regards to all Flanders-matters. Her husband had a slight fall from grace in 1388 when his nephew came of age and chose to favour the advice of a faction known as “the Marmousets” over that of his uncles. To be honest I don’t blame him, the four regents were not exactly selfless and all had their own agendas which had at times caused a bit of turmoil in French governance. Philip however was able to regain power due to the mental instability of his nephew whose mental health only got worse throughout the 1390’s suffering severe episodes of severe hallucinations. Philip’s seizure of power was a bit of a disaster really as it led to a giant chasm within the House of Valois. Philip’s other nephew Louis the Duke of Orleans resented his uncle taking power and believed he should have been named regent. One of the main sources of disagreement was money; both wanted access to the royal purse for their own personal reasons – Louis to fund his lavish lifestyle and Philip to fund his expansionist ambitions. During a rare moment of sanity in 1402, Charles VI confirmed his brother as regent over his uncle. Philip died in 1404 and his and Margaret’s son John took up the mantle of Duke of Burgundy as well as taking his father’s place in the feud with the Duke of Orleans. When she died a year later in 1405 her son inherited all of her territories too, meaning that Flanders completely lost all independence from Burgundy. Her son a rash, ruthless politician would go on to cause a political catastrophe in 1407 when he ordered the assassination of the Duke of Orleans which led to the eruption of the Armagnac-Burgundian Civil war that culminated in John’s own assassination in 1419. The backdrop to all of this was the Hundred Years War which at various points France appeared to be losing, usually due to the idiocy of the people running the show. In the midst of all this was the emergence of one of my historical favourites Yolande of Aragon (she was married to Philip’s nephew Louis) and in my profile of her, the Armagnac-Burgundian is talked about in more detail if you’re interested!

Maria Francisca of Savoy was born in Paris in 1646 the daughter of Charles Amadeus of Savoy Duke of Nemours and Élisabeth de Bourbon-Vendôme; her mother was the granddaughter of Henry IV King of France and his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrees (keep your eyes peeled for a post about her soon) which made her a half first cousin once removed of Louis XIV. She was the youngest of her parents children to survive to adulthood; her sister Marie Jeanne Baptiste was later the Duchess of Savoy, mother of Victor Amadeus II King of Sardinia, regent of Savoy and grandmother of Louis I King of Spain and Louis XV King of France. Her father died in 1652 when she was just 6 after stupidly getting into a duel with his brother in law François Duke of Beaufort; her father’s sudden death meant that the two girls were placed under the guardianship of their father’s successor/their paternal uncle Henri II Duke of Nemours however their mother & maternal grandmother Françoise of Lorraine were the dominant figures of their shared childhood and were responsible for the arranging of the girls marriages. As a lil side note, Maria Francisca’s side of the family were a tad controversial; her maternal grandfather had been involved in the Fronde (which was a series of mini civil wars in France between 1648 and 1653 when Louis XIV was just a kid and the country was under the authority of his mother Anne of Austria and Cardinal Mazarin; the aim of the Fronde was to limit the growing power of royal government; it failed and Louis XIV was so traumatised by the violence that he ended up becoming “Mr Royal Absolutism I am the State”. So mission failed) and had been accused of trying to poison Cardinal Richelieu whilst her sister Marie Jeanne Baptiste was accused by Cardinal Mazarin of being too ambitious (I’d just like to point out that no man has ever been accused of being too ambitious). Now the political situation in Portugal as this time was a complicated one; Portugal & Spain had been unified in 1580 by Philip II however unification hadn’t lasted and the Portuguese Restoration War (between 1640 and 1668) had culminated in the accession of John IV as King of Portugal. Now John’s son Alfonso VI had succeeded him in 1656 under the regency of his mother Luisa de Guzmán; after taking power for himself Alfonso egged on by his power-hungry advisor Castelo Melhor (there’s nearly always a morally bankrupt power hungry advisor causing chaos, isn’t there) removed all authority from his mother and sent her to a convent. Alfonso taking the reins of government was a little bit of a problem because the man was not exactly sane; he suffered from some sort of mental instability as well as being physically disabled – it’s believed his mental and physical ailments were a result of an illness (possibly meningitis) he suffered as a toddler which left him paralysed on the left side of his body. Now the Portuguese court was split; half the court were pro-English whilst the other half were pro-French. Charles II King of England married Alfonso’s sister Catherine in 1662 and the French concerned that the pro-English faction at the Portuguese court would benefit from that marriage, decided to arrange a Portuguese-French union to offset that. Charles II wasn’t exactly thrilled with French scheming (when is any King of England ever happy with French scheming) but Louis XIV managed to persuade him to agree to the marriage by giving him the unpaid portion of Catherine’s dowry. Gold, evidently heals all wounds. Maria Francisca and Alfonso were married in August 1666 and the marriage was almost immediately a failure. Alfonso left the wedding early (without his wife) and showed little interest in actually consummating it. Maria Francisca bless her heart, tried to make it work; she was very intelligent and evidently had an interest in being involved in matters of state, especially in advocating on behalf of France. That put her in direct conflict with Castelo Melhor (her husband’s morally bankrupt power hungry chief advisor) who made it his mission to deprive her of any and all influence. Maria Francisca thus found herself allied with her brother in law Pedro who like her was not a fan of Melhor and was still upset over the treatment of his mother. He was noted to have little affection for his older brother. The two became deliciously effective partners-in-crime and if the rumours are to be believed lovers; Maria Francisca convinced her cousin Louis XIV that Pedro being King was more beneficial to France than Alfonso whilst in September of 1667 they managed to force Melhor into exile. Two months later Pedro and Maria Francisca managed to garner enough support to overthrow Alfonso; although he nominally remained King, Pedro was now regent and thus in control. Maria Francisca made the decision to retire to a convent and asked her marriage be annulled on the grounds that it was never actually consummated. The French cleric Cardinal de Vendôme agreed and granted her the annulment (this is where I point out that the Cardinal happened to be her uncle which is absolutely not a coincidence). She remained in the convent for a few months until she abruptly left and promptly married Pedro in September of 1668. Alfonso meanwhile was sent initially to the island of Terceira where he remained for seven years before being allowed to return to the Portuguese mainland where he was effectively under house arrest at Sintra, where he died in 1683. Between 1668 and 1683 Maria Francisca was the wife of the regent and despite having annulled her marriage to Alfonso, continued to be treated basically as the Queen. She was incredibly influential and became known for her involvement in matters of state. During their marriage she was only able to bear her husband one child – a daughter Isabel Luisa (born in 1669) – despite her failure to bear an heir for the House of Braganza (which might I add, had 0 male heirs left), the discussion of divorce or annulment was never raised and in 1674 Pedro named his daughter the heir to the throne after him. Maria Francisca and her sister Marie Jeanne Baptiste then appear to have come up with a mutually beneficial plan in which Maria Francisca’s daughter would marry Marie Jeanne Baptiste’s son; not only did this secure Maria Francisca’s daughter’s place as heir but it almost meant that Marie Jeanne’s son would leave Savoy and move to Portugal, allowing her to remain as the ruler of Savoy in his stead. Unfortunately for them, their plan failed when it became clear that a) the laws of the Portuguese Cortes prohibited a heiress of the kingdom marrying a foreign prince and b) a large swathe of the court in Savoy opposed the idea. During the years that Pedro ruled as regent, Maria Francisca built a strong pro-French faction at court that triumphed over the more pro-Spain faction. In September 1683 her ex-husband/brother in law Alfonso died and Maria Francisca was once again finally Queen of Portugal with her husband being crowned. She didn’t keep her restored position for long however; just three months later in December she died, having suffered from ill health for quite some time. Upon her death much of the Portuguese court then tried to convince Pedro to immediately marry. He refused and seemed genuinely grieving for his wife. He however was eventually forced to remarry in 1687 to Maria Sophia of Neuburg – his and Maria Francisca’s daughter Isabel Luisa was childless and due to ill health unlikely to bear any children of her own (she ended up dying at the age of 21), meaning that Pedro needed heirs asap. Maria Sophia was very different to Maria Francisca; she had no involvement in politics and was described quite frequently as “gentle”, a descriptive word I’m not sure was ever used to describe Pedro’s first Queen. Maria Sophia was able to give Pedro that all important heir however it is Maria Fransisca not Maria Sophia that Pedro was buried with.

Elizabeth Richeza of Poland was born in Poznan in 1288 the daughter of Przemysł II of Poland and Richeza of Sweden; her mother died when she was just a small child (the date is unknown but it’s widely believed she died between 1289 and 1292) leading to her father remarrying – he married his third wife Margaret of Brandenburg in 1293. Marrying Margaret turned out to be a very big mistake on Przemsył’s part; in 1296 he was kidnapped and murdered by various members of Margaret’s family supported by disgruntled Polish nobles who opposed him. The depth of Margaret’s involvement is unclear; it was assumed due to the fact the murderers were her own kin, that she was in on the plot however it’s entirely possible she had no involvement, I mean as we all know from the entirety of European history, men do not usually check with the women in their family before making questionable choices. In the aftermath Margaret was granted guardianship of Elizabeth-Richeza or Ryksa as she was known in Poland, meaning that the poor girl was basically forced to be surrounded by the family that had murdered her father and orphaned her at the age of 8. An absolute nightmare. Now despite her tender age Ryksa was already engaged; a marriage had been arranged between her and Margaret’s brother Otto around the same time that Margaret had married her father. Margaret and Ryksa moved to Brandenburg so the latter could get to know her fiancée. He however died in 1299 and Ryksa, perhaps not wanting to be around her father’s murderers, promptly left Brandenburg and returned to Poland. Otto’s death made Ryksa’s life 100x more complicated because as the only child of the last male member of the Piast Greater Poland line/the first King in almost two centuries, she was wanted as a bride by every possible contender for the Polish crown. The nobility of Poland were determined to choose the next King and thus took a special interest in the identity of her husband; they eventually settled on Wenceslaus II King of Bohemia, a widower seventeen years her senior. Wenceslaus wasn’t exactly fond of the idea of marrying a child so the wedding was delayed until she was 15. Whilst waiting to marry, she was put under the guardianship of the aunt of her husband-to-be in Prague. The marriage between Ryksa and Wenceslaus II took place on 26 May 1303 at Prague Cathedral in a ceremony that was a dual wedding-coronation; her name was a Polish one and not a name used in Bohemia resulting in her being forced to adopt the name Elisabeth. Very little is known about their very brief marriage – they had one single daughter Agnes born in 1305. Wenceslaus died six days later leaving Ryksa a seventeen year old widow. Her step-son Wenceslaus III succeeded as King of Bohemia & Poland (he also had a claim to the Hungarian throne) however he only ruled for a year until 1306 when he was brutally murdered. Ryksa who had spent the last year being an unimportant chess piece in Eastern European politics suddenly gained new importance as the widow & step-mother of the last two kings, and once again she became a hot commodity on the European marriage market. She ended up marrying Rudolph II of Austria & Styria who was the son of Albert I of Germany. His father backed him becoming King but marriage to Ryksa all but confirmed his new crown. He didn’t however wear it for long because he died just a year later once again causing a succession crisis. In his will he granted her, her dowry and a sizeable fortune; she left Prague and settled in one of her dower towns. Her new found retirement however didn’t last very long and she found herself pulled into a civil war over the Bohemian crown. She backed her brother in law Frederick, a decision that backfired ever so slightly when his opponent Henry of Carinthia soon occupied Ryksa’s lands forcing her to flee. Upon her return, she sought to turn her court into a centre of European culture and art; this second retirement didn’t last long either. In 1310 John of Luxembourg married Ryksa’s former step-daughter Elizabeth (daughter of her first husband Wenceslaus II) and thus claimed the Bohemian throne. An anti-Luxembourg faction of Bohemian nobles rallied around the extremely popular Ryksa who formed an alliance with Henry of Lipá, a powerful Bohemian magnate who was both John of Luxembourg’s chamberlain and Supreme Marshal of the Kingdom of Bohemia. In the absence of the King, he thus served as regent. The two started off as allies but soon fell in love. Between 1310 and 1315 Henry’s power slowly grew, much to the consternation of John who was pretty horrified when he realised Henry and Ryksa were a couple (if they married Henry would thus have had a claim to the throne). In order to weaken the position of the Bohemian nobles, Henry especially, John removed Henry of those powerful positions and imprisoned him. What he didn’t anticipate was that Ryksa was SO popular in Bohemia that would be an uproar amongst both the public and the nobles. Her popularity and political influence was so strong that John feared the country was on the verge of civil war and released Henry in April 1316. This did little to heal the tension between John and the ever independent Ryksa and in 1317 she betrothed her daughter Agnes to the Silesian duke Henry I of Jawor. With Ryksa’s consent Henry began a series of military expeditions against John as well as financing and encouraging rebellions against him. Eventually the Holy Roman Emperor Louis IV had enough of the shenanigans and intervened with a peace treaty being signed. Ryksa apparently only agreed to sign said treaty if John restored Henry of Lipá (with whom she was still in a relationship) to all his powerful positions. Ryksa and Henry then settled at their own court in Brno; they were never able to marry – as a Dowager Queen twice over not to mention her father’s heir, her rank was far higher than his – as previously mentioned it also gave him a claim to the throne that could have caused yet another civil war. Despite that they would remain together until his death in 1329; a man and woman unmarried openly living together in the 1300’s was controversial to say the least which has led some historians to suggest that the two may have secretly wed however there’s no evidence of that. Relations between John and Ryksa were from that moment on relatively peaceful – he recognised her as a powerful opponent and was forced to play nice with her for the sake of peace. Henry’s death in 1329 absolutely devastated Ryksa who became a nun in the aftermath; she dedicated the rest of her life to funding the construction of churches, Cistercian convents and the crafting of illuminated hymn books. In 1333 she and her daughter Agnes went on a long pilgrimage to the shrines of the Rhine. Elizabeth Richeza Dowager Queen of Poland and Bohemia, beloved by both the Polish and Bohemian people died in October 1335 at the Cistercian monastery in Brno and was buried besides Henry the love of her life.

Elizabeth of Brandenburg was born in 1425 the daughter of John of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Barbara of Saxe-Wittenberg (fun fact her father was given the fancy nickname John the Alchemist) and was raised alongside her sisters Dorothea who became Queen of Denmark and Barbara who became Marchioness of Mantua. Due to a convoluted set of political complications that I don’t have the time to explain, Elizabeth’s father renounced his rights to the succession in Brandenburg and instead received the Franconian possessions of the House of Hohenzollern. Elizabeth’s family was, well considered to be a bit of a pain in the behind, in the region and her uncle in particular Frederick II was noted for his significant ambition and constant meddling in matters that had little to do with him. When she was around 13-16 (sources differ on when the wedding actually took place) it was agreed that she would marry Joachim I Duke of Pomerania-Stettin as a way of sealing the treaty between Brandenburg and Pomerania – he had originally been engaged to her sister Barbara however the engagement had fallen through and Barbara had married Ludovico Gonzaga instead. There’s very little known about their marriage and whether it was a happy one or not; we do know it was LEAGUES better than her second marriage but we’ll get to that. During the course of their marriage they only had one son Otto who was born in 1444. Joachim died 1451 after less than 15 years of marriage – it’s believed he died of the Black Death which let’s be honest, is a pretty unfortunate way to go. This left their seven-year-old son as the new Duke. Elizabeth was able to secure her son’s new position and had him placed under the guardianship of her uncle Frederick II of Brandenburg, whilst her late husband’s cousin Wartislaw IX Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast was named regent (albeit not officially) of her son’s duchy. Elizabeth evidently had some influence and was involved in the regency which culminated in 1454 in her marrying Wartislaw’s son and heir also named Wartislaw. The marriage was a fairly miserable one and the two pretty much loathed each other; they did however have two sons. When her father in law died in 1457 he named his sons Eric II and Wartislaw X as heirs alongside Elizabeth’s son Otto. This led to somewhat of a dispute over land and wealth; not only did Eric and Wartislaw disagree on who should rule what but they were also slightly miffed at having to give Otto a part of Pomerania. They were particularly concerned about the fact that Otto was backed not just by Elizabeth by also by Elizabeth’s father (who despite abdicating power still had some importance) and uncle Frederick II who as I previously mentioned, thoroughly enjoyed involving himself in matters that were not particularly relevant to him. He demanded part of Pomerania on Otto’s behalf and was willing to do just about anything to get it. The year 1464 was a particularly devastating one for Elizabeth; not only did her father die but so did her three sons, the youngest two of whom were under the age of 10. It’s believed they died of the plague. Elizabeth was by all accounts heartbroken. With her eldest son’s death the Pomerania-Stettin line of the House of Griffins died out, which led to her uncle good old Frederick claiming that her sons lands was a fief of Brandenburg and should from that moment on belong to their family whilst Wartislaw and his brother Eric claimed that it should belong to them. Negotiations were ongoing however her marriage to Wartislaw became so horrendous that Frederick abruptly called off negotiations, leading to a conflict now known as the Stettin War of Succession. As much as I’d like to think Frederick was merely defending his niece, his decision to break off negotiations was probably a political decision more so than anything else. Frederick granted Elizabeth a number of lands; she promptly left her husband and retired to said lands. Although retired she remained a supporter of her uncle’s cause and her position as the mother and widow of multiple dukes was used as propaganda against her estranged husband. The last record we have of Elizabeth was in January 1365. Now there’s no record of her death so it’s very possible she continued living for some years afterwards but had absolutely no involvement in any political matters. Ultimately Elizabeth would have the last laugh – although her husband’s family retained Pomerania-Stettin they had to accept Elizabeth’s family as overlords. Pomerania-Stettin would remain a fief of Brandenburg for decades.

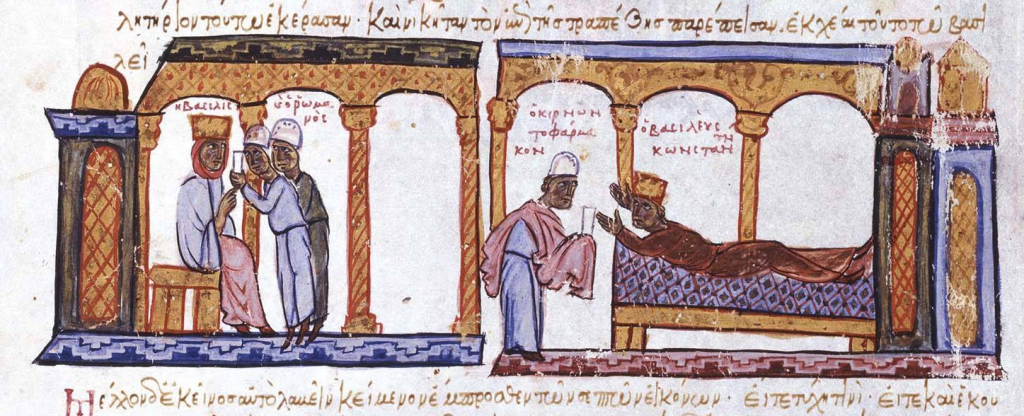

The history of the Byzantine Empire is, let’s be honest, not devoid of very cool women (hello Irene of Athens) and this woman here – Theophanu – is one of them. Now her origins are very interesting; she was born with the name Anastasia or Anastaso in the Peloponnesian region of Lakonia probably in the city of Sparta circa 941, the daughter of a tavern owner whose name we believe was Craterus. Nothing is known about her mother. In 956 when she was around 15-16 she met Romanos the son and co-ruler of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII. How they met, we have absolutely no idea. What we do know is that Romanos fell head over heels with her and against the wishes of his father (who himself had married a princess and who was not best pleased at his son being in love with a dirt poor commoner) he married her thus making her royalty. Cinderella who? Upon marriage she took on the name Theophanu, and was (this won’t surprise you) immediately unpopular with the Byzantine elite due to her humble origins, despite her beauty and obvious intelligence. It’s also believed she clashed with her father in law, which was problematic considering the fact he was the Emperor. Part of the tension between them apparently seemed to stem from Constantine’s concern that Theophanu had far too much influence over his son. In 959 Constantine dropped dead. And I mean that literally. The man had been a beacon of health until one day, he died, suddenly and unexpectedly and as is the case in most unexplained deaths, everyone immediately jumped to the conclusion of poisoning with Theophanu as the lead suspect. Hence the picture above. Romanos thus became the sole ruler of the Byzantine Emperor, with Theophanu as his Empress; he quickly decided to purge the court of his father’s favourite officials and advisors and in the years following his accession he also apparently dismissed his mother Empress Helena from court and sent his sisters to nunneries. The exact circumstances surrounding these de-facto exiles isn’t clear and whilst Theophanu was blamed for her husband’s decisions, it’s possible there were other factors at play. I don’t personally think Romanos would have done all that simply because Theophanu didn’t like them – there’s likely to have been incidents or particular problems that lead to the controversial exiling of his family. Now Romanos was not a particularly war-hungry Emperor nor was he very politically shrewd; during his short four year reign he relied on a small group of very loyal advisors and Theophanu who became extremely influential, in many ways helping to dictate policy. Whilst this served Romanos well, it created a ton of problems long term, as his decision to rely on a small number of advisors and thus ignore the wider bureaucracy particularly the military, caused quite a significant amount of resentment. In early March 963, Theophanu gave birth to their only daughter and third child overall Anna (they already had two sons Basil & Constantine who were 5 and 3 respectively). Romanos organised a hunting expedition to celebrate and whilst on said hunting expedition, he fell dangerously ill and died on the 15th March 963. Accusations that Theophanu was responsible for his death, are to be frank, absolutely ludicrous. She had absolutely no reason to murder her husband; by doing so she would have gained absolutely nothing and potentially lost everything. She was safe and secure as an anointed Augusta; her husband’s death however made her the widowed mother of three very young children with no powerhouse political family to protect and support her, and a ton of enemies waiting in the wings to destroy her. I’d also like to point out she’d just given birth and was literally still in bed. At this point in Byzantine history, hereditary ascension was more of a matter of tradition, not law (or in the words of Barbarossa from Pirate’s of the Caribbean “the code is more what you’d call ‘guidelines’ than actual rules”) and although her boys were immediately declared co-emperors with her as their nominal regent, the positions were in name only and Joseph Bringas a powerful eunuch at court was the one really wielding power. Theophanu did not even remotely trust Bringas who she perceived to be power hungry (and she may have had a point; the man had a ton of enemies including Basil Lekapenos the illegitimate son of her husband’s grandfather Romanos I and therefore her husband’s half-uncle who was quite influential at court). Theophanu thus found herself in a position of having to find a way to a) secure her position, b) save her life and c) secure the future of her children. To do that she needed a protector. Passing over a plethora of would-be suitors who were eager to woo the very beautiful newly widowed Empress, she made an alliance with Nikephoros Phokas a celebrated military commander who the army had promptly proclaimed as their favoured choice for emperor just after Romanos’ death (remember the military were not exactly Theophanu’s #1 fans). Nikephoros was also one of Joseph Bringas’ aforementioned enemies. The Theophanu and Nikephoros marriage was seemingly a good political idea; marriage to the Empress gave him legitimacy whilst he gave a sacred oath to protect her children. Theophanu however decided to have a contingency plan on the side and allegedly took her new husband’s very handsome and inexplicably charming nephew John Tzimikes, another popular and influential general as a lover. In August of that year Nikephoros took control of Constantinople despite the resistance of many of Romanos’ former counsellors including Bringas who was swiftly dealt with. Nikephoros was crowned in the Hagia Sophia on the 16th August and married Theophanu shortly thereafter. The marriage, unsurprisingly provoked a ton of opposition from the church particularly the very very very conservative Patriarch Polyeuctus who was well known to have quite considerable enmity towards Theophanu who he had long considered a bit of an upstart. Both Theophano and Nikephoros were widowed, and the Orthodox Church at the time only begrudgingly accepted remarriage. Polyeuctus demanded that Nikephoros perform a penance for getting re-married, and when Nikephoros showed some resistance, he banned him from kissing the holy altar. Further complications arose when it was alleged that Nikephoros was godfather to at least one of Romanos & Theophano’s children, which placed the couple within a prohibited spiritual relationship (thus illegal under Orthodox law). Nikephoros organised a council which nullified the relevant rules, however Polyeuctus was not so easily dealt with and soon declared Nikephoros and Theophanu excommunicated until the former sent the latter away. In response a number of Nikephoros and Theophanu’s inner circle testified that the new Emperor was not in fact godfather to any of Theophano’s children and thus there was no legal reason to oppose the marriage. Polyeuctus was as bitter and resentful as ever but ultimately relented allowing Nikephoros to return to full communion and keep Theophano as his wife. That ladies and gentlemen is what we call a win for Theophanu. Now the thing is Nikephoros proved to be no more politically astute that Romanos and his gruff military style proved counter-productive to the workings of government as well as causing a number of diplomatic headaches, namely war on multiple fronts. As many monarchs will attest, the problem with war is that it’s costly and what are monarchs usually forced to do to fund, said costly wars? Raise taxes, and let’s be honest higher taxes are no fun for anyone and are usually very unpopular, especially when they coincide with a few years of poor harvests which have cause widespread famine in some areas of the empire. OOPS. When Nikephoros tried to mitigate the damage his foreign policy was doing to the people, he did so by limiting the wealth of monasteries which in turn only upset the church. To top off the chaos, he also managed to fall out with a number of his closest supporters including his nephew John Tzimiskes, who if you recall had allegedly begun sleeping with Theophanu shortly after she married Nikephoros. John and Nikephoros had some sort of a falling out, the origins of which aren’t clear (I’d wager infidelity might have played a role) and John was quickly dismissed from court. Feeling pretty aggrieved by the situation, he retaliated by conspiring with his good friend Basil Lekapenos (the uncle of Theophanu’s first husband who had never been a huge fan of Nikephoros and who was determined to see his own blood i.e Theophanu’s sons on the throne instead of Nikephoros brother Leo who it was believed he want to succeed him) and Theophanu herself; it’s thought she had tired of Nikephoros’ never ending stream of bad political decisions. A number of disgruntled generals who Nikephoros had also enraged supported them, leading to a convoluted plot which culminated in Nikephoros’ murder (FUN FACT: the inscription on Nikephoros’ sarcophagus ends with “Nikephoros, who vanquished all but Eve” in reference to Theophanu). The exact details of his death aren’t clear and what we do know is likely to have been heavily embellished over the years; John having been sent away from Constantinople allegedly crossed the Bosphorus into the harbour of the city, was then smuggled into the palace and into the bedroom of Nikephoros by Theophanu who apparently left the bedroom doors unlocked for him to enter. He then murdered his uncle and proclaimed himself Emperor. To top it off he then announced plans to marry Theophanu. The problem with that was Theophanu at this point had an astonishingly bad reputation (having been accused of murdering the last three emperors) and her old nemesis Patriarch Polyeuctus, appalled at having to deal with Theophanu’s shenanigans yet again, flat out refused to perform the coronation and demanded that John a) punish those who assisted him in the assassination, b) repeal of all Nikephoros decrees that he claimed were against the church and c) dismiss Theophanu from court. Theophanu’s ally/uncle by marriage Basil Lekapenos promptly turned against her and advised John to send Theophanu away. John evidently chose the legitimacy of his reign over any sentimentality he may have felt towards her and promptly agreed to send her into exile on the island of Prinkipo. Now if you remember, Theophanu had allegedly been responsible for her husband sending all his sisters to live as nuns in convents; this ended up biting Theophanu on the behind because the minute, she was exiled, John brought those princess-nuns out of their convents and immediately married one of them – Theodora – giving his reign further legitimacy. John would only rule for seven years with Theophanu spending the entirety of those seven years in exile. Her sons Basil and Constantine were technically under the guardianship of her former lover turned enemy however Basil Lekapenos her former ally/uncle by marriage acted as a protector of sorts to the two boys. John died suddenly in 976 returning from his second campaign against the Abbasids; his death like so many in Theophanu’s life was abrupt and unexpected and once again rumours of poison emerged. Except this time our girl Theophanu was innocent of all charges. It’s believed that it was Basil Lekapenos that had John murdered – apparently to guarantee that Theophanu’s now grown up sons would take power of the empire. Literally the first thing her boys did upon taking power was to recall their beloved mama back from exile. She returned to Constantinople and was given all the honours due to the mother of the co-emperors. She evidently upon her return had some political influence although exile seems to have mellowed her somewhat and she was more discreet in her influence than before. The last reference to her was in 978 just two years after her return when she beseeched the retired Georgian general T’or’nik of Tao to broker an alliance between her sons and his former overlord David III of Tao; she wanted David’s support against the Byzantine general Skleros who was revolting against the crown. She’s not mentioned again and it’s believed she died in the early years of her sons reign probably around 980.

Beatrice of Naples (also known as Beatrice of Aragon) was born in November 1457 in Naples, the daughter of Ferdinand I King of Naples and Isabella of Clermont; now her father was a particularly wily individual who spent most of his life fighting off various imperial powers who wished to rule Naples. He was also one of the most influential and feared monarchs of the time and is now considered to have been one of the most shrewd political minds of 15th century Europe. Due to his two marriages and numerous mistresses, Beatrice grew up with a ton of siblings; she had four brothers, one sister (Eleonora who became the Duchess of Ferrera), eight half sisters and four half brothers. Alongside her siblings she received an exemplary education at her father’s court. In 1474 at the age of seventeen she was engaged to Matthias Corvinus King of Hungary & Bohemia; they married two years later (she thus became his third wife) and her coronation took place in December of that year. Matthias, like her father spent a whole lot of time at war and the marriage was arranged as a way of bringing an alliance between the two countries; this alliance was to be very fruitful in the years that followed, for example in 1480 an Ottoman fleet seized Otranto (a seaside city in the Kingdom of Naples), Matthias sent one of his best generals to recover the city. A similar situation happened a year later when Matthias took the Neapolitan city of Ancona under his protection with a big old Hungarian army to do the heavy lifting. Now the marriage between Matthias and Beatrice appears to have been a relatively good one; she was keen to bring some Italian flair into the court of Hungary much to the approval of Matthias who had a keen interest in Italian Renaissance art and literature. This was something they clearly bonded over and she encouraged his creation of the Bibliotheca Corviniana (which became one of the most impressive Renaissance libraries outside of Italy) and the establishment of an academy. They also worked together on their summer palace Visegrad which became the first palace outside of Italy to have Italian Renaissance architectural features. Now Beatrice was clearly intelligent, and having watched her father rule so shrewdly and ruthlessly for so many years, she was clearly politically minded. Luckily for her Matthias (unlike many husbands of the period) wasn’t against the idea and the two became a bit of a power couple, sharing a certain degree of ambition. She was said to have influence over Hungarian policy – in 1477 she accompanied him during the invasion of Austria and two years later was part of the negotiations for a peace treaty between Matthias and Vladislaus II. The marriage, which remained childless, hit a bit of a rocky patch in 1479 when Matthias awarded his illegitimate son John Corvinus a fief and invited John’s mother aka his former mistress Barbara Edelpock to court (the affair had ended when Matthias and Beatrice married). Clearly Matthias wasn’t expecting Beatrice to bear an heir and thus was laying the groundwork for his illegitimate son to rule after him. Beatrice was unsurprisingly a little offended and not at all thrilled at her husband’s former lover hanging around. Beatrice refused to accept John as her husband’s heir which meant the political situation was a lil bit complicated when Matthias died a decade later in 1490 (yes she remained stubborn for a decade which is dedication to a grudge to say the least). He likely died from a stroke however rumours, because there are always rumours, suggested that Beatrice had poisoned him. Now Beatrice was certainly upset at her husband, but she wasn’t that upset; the idea that she poisoned him is a stupid one and there’s absolutely no proof. These rumours are likely to have been a smear campaign; in that period Italians had a reputation for poisoning, particularly Italian women; see Catherine de Medici and Bona Sforza, two Italian born women who became Queens of other European countries – France and Poland respectively – and were accused of all sorts via the use of poison. Upon his death Beatrice managed to do two things a) she managed to keep John off the Hungarian throne and b) managed to stay Queen by gathering enough allies amongst the Hungarian nobility to secure her authority – those nobles demanded she remain as Queen by marrying the next Hungarian monarch. At the gathering of parliament to select the next King, Beatrice represented the monarchy with the Hungarian crown by her side – the winner of the election was Vladislaus II previously an opponent of her late husband’s who she married in 1491 with the support of the Hungarian nobles. This marriage, which only lasted two years, was also childless and ended in absolute disaster; Vladislaus had previously been married to Barbara of Brandenburg however their divorce hadn’t been sanctioned by the Pope and so there was a bit of a question mark as to the legality of the divorce. Vladislaus being a world class idiot also claimed he’d been forced into his second marriage by Beatrice and the Hungarian nobility and wanted out. These various issues resulted in a commission that was set up in 1493 to figure it all out. Eventually the Pope (also being a world class idiot) decided the marriage was illegal and annulled it. Having lost her position as Queen, Beatrice was forced to return to Naples. It’s quite insane when you think Beatrice wasn’t even forty by the time this all happened. After her return to Naples, she lived the rest of her life in relative peace albeit without the power and prestige she’d become accustomed to.

Most of the women on this list are European Queens, however with this next woman we’re heading over to North Africa. Very little is known about the early years of Shajar al Durr’s life; her real name and place of birth have been lost to history although it’s believed she was of either Armenian or Turkic origin. As a child she was forced into the slave trade (like with most details about her childhood, the circumstances of her enslavement are unknown). Eventually (although we don’t know when) she was brought as a slave by al-Salih Ayyub the son of the Egyptian ruler al-Kamil; now he was a member of the Ayyubid dynasty which was made up of a number of different little emirates all ruled by different members of the family – whoever ruled Egypt however was seen as the main man of the dynasty. In 1234 al Kamil removed al-Salih from the line of succession in Egypt and sent him to rule in Damascus, pretty much exiling him; this was because al Kamil suspected his son was conspiring against him with the Mamluks. Shajar went with him and they remained there for a number of years. Very little is known of Shajar in those years, although the fact she remained in such close proximity to al-Salih would suggest he developed quite the fondness for her. al Kamil died in 1239 and because nothing is ever simple, his death caused a few succession issues. He split his territories between his sons, giving the most important kingdom – Egypt – to al Salih’s half brother al-Adil whilst al Salih took complete control of Damascus. Some of the Emir’s in Egypt were unhappy with this new political landscape and beseeched al Salih to dethrone his brother and invade Egypt. He then attempted to forge an alliance with his uncle al-Salih Ismail who he hoped would join him at Nablus for the campaign to invade Egypt. Ismail however took his sweet time in agreeing to the plan and failed to send troops leading to al-Salih and his advisors growing increasingly suspicious. A whole series of scheming shenanigans then took place which culminated in Ismail (with the support of the Ayyubids of Kerak, Hama & Homs) invading Damascus instead of Egypt. al Salih was abandoned by his troops and ended up being taken prisoner by al-Nasir Dawud. Shajar by virtue of belonging to him, was also imprisoned and it was during her imprisonment that she gave birth to his son Khalil. In April 1240, it all kicked off between al-Nasir and al Adil II culminating in him releasing Shajar and al-Salih and forging an alliance with the latter, with the agreement that al-Salih would invade Egypt and give Damasus to al-Nasir. The plan was successful and al Salih made a glorious triumphant entry into Cairo (with Shajar by his side) in June 1240 becoming the paramount ruler & big cheese of the Ayyubid dynasty. Shortly afterwards although we have no idea about when exactly, he and Shajar married, with her thus becoming his legal wife. For almost a decade he ruled with her by his side – it’s believed she had a decent amount of influence. In 1249 al Salih was in Syria when he received word that Louis IX of France was assembling a Crusader army in Cyprus with the intention of invading Egypt. Despite being incredibly ill, he promptly returned to Egypt – in June of that year the Christian army landed in the abandoned town of Damietta and began to attack. In November with the fighting ongoing, Al Salih died without leaving a will naming his successor; this would have caused absolute chaos were it not for his incredibly competent widow who ordered the commander of the Egyptian army and the chief eunuch who controlled the palace, to conceal her husband’s death. They were clearly not in the mood to argue with her and his body was secretly removed from the palace and transported elsewhere – she then summoned her step-son al-Muazzam Turanshah to become the next Sultan (evidently her own son had died by this point). al-Muazzam had been exiled to Hasankeyf following a disagreement with his father a few years before however Shajar made the decision that he would rule next. What followed was an extremely convoluted series of shenanigans meant to convince everyone that Al-Salih was merely unwell instead of cold-stone dead; documents were forged and his handwriting copied, his chief minister, now seemingly loyal to Shajar, began issuing decrees and orders and the soldiers and high officials were ordered to swear an oath of loyalty to the Sultan and his heir. Shajar played her part beautifully – she continued to have food prepared for the Sultan and brought to his tent whilst she also relayed orders from him to his government ministers. She couldn’t however keep news of his death quiet forever and news of his death soon reached the ears of the crusaders in Damietta. Once Louis IX’s brother Alfonso the Count of Poitou arrived with a ton of reinforcements, they decided to march on Cairo. They first attacked the Egyptian camp of Gideila and then began moving towards the town of al-Mansurah. Shajar and the military commander Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari more commonly known as Baybars, came up with a genius plan to defend the important town. The plan was unsurprisingly successful and in the course of the fighting Robert of Artois, another one of Louis IX’s brothers, was killed whilst the majority of the crusader army was completely destroyed. Months later in February 1250 her step-son al-Muazzam Turanshah finally arrived in Egypt and was almost immediately crowned, allowing Shajar to publicly announce her husband’s death. al-Muazzam then left to complete the destruction of the crusader army; during the Battle of Fariskur, Louis IX the King of France was captured. This is where things start getting real messy. You see al-Muazzam Turanshah had no intention of letting his step-mama have any authority over his Sultanate whilst Shajar had grown pretty accustomed to power. She was also backed by the Mamluk’s and the old guard of her late husband’s government. al-Muazzam then made the mother of all mistakes; he decided to completely go against her. He detained a number of his father’s advisors more specifically the ones he suspected were loyal to her and summoned a load of his pals from Hasankeyf to replace them; he then ordered Shajar (who at this point we believe was in Jerusalem) to hand over all wealth, jewels and land given to her by his father. Feeling pretty understandably pissed off about the situation, Shajar complained to the Mamluk’s who were livid at the disrespect shown to her. They were also pretty upset at rumours that al-Muazzam was a bit of a drinker, a no-no in Islamic society, especially medieval Islamic society. Whether he really did have a drinking problem or merely the victim of slanders meant to ruin his reputation, we can’t be sure. On the 2nd May 1250 in the midst of the bickering over absolute power, al-Muazzam was assassinated. The degree of Shajar’s involvement in this little incident is pretty unclear; it’s entirely possible she had nothing to do with it. It’s also entirely possible she ordered it. With his death, there was now one major problem – the Sultanate lacked a Sultan. You know what the Sultanate did have? A Sultana. The Mamluk’s and Emir’s were aware of this fact and promptly came to the conclusion that the best course of action was to offer Shajar the nice, new role of monarch. Shajar (unsurprisingly) happily accepted and took the royal name “al-Malikah Ismat ad-Din Umm-Khalil Shajar al-Durr”. She was also given a few other titles including “Malikat al-Muslimin” (Queen of the Muslims) and “Walidat al-Malik al-Mansur Khalil Emir al-Mo’aminin” (Mother of al-Malik al-Mansur Khalil Emir of the faithful). She then set about stamping down her authority – it was ordered that she be mentioned in Friday prayers in mosques (like all male monarchs), new coins were minted with her titles and she then sent Emir Hossam ad-Din to neogiaite with Louis IX King of France who was still chilling, albeit under guard in Al Mansurah. Negotiations led to an agreement that Louis IX would leave Egypt alive however he had to pay half of the ransom imposed on him and surrender Damietta. This was huge because it marked the end of the Crusader’s ambition to conquer the Southern Med. Interestingly in mosques she was referred to as “Umm al-Malik Khalil” (Mother of al-Malik Khalil) and “Sahibat al-Malik as-Salih” (Wife of al-Malik as-Salih) and she also used those names when signing official documents. Referencing her late husband and son was a very shrewd move on her part; as both a woman and someone who wasn’t necessarily the monarch by birthright, she needed to secure as much legitimacy for her reign as possible. Referencing her husband and son did that to a degree but not quite enough. Whilst some were thrilled at her installation as the new monarch, others were not; the Syrian Emirs refused to pay homage and instead pledged allegiance to al-Nasir Yusuf the Ayyubid Emir of Aleppo; the Abbasid Caliph al-Musta’sim also refused to recognise her as Egypt’s ruler. This was a major issue; in that era it was believed the Sultan (or in this case Sultana) could only gain legitimacy through the recognition of the Abbasid Caliph. Her position was basically untenable at this point; there was no way she could have continued ruling. It was then decided that Shajar would step down and Izz al-Din Aybak, a military commander would be installed as Sultan; it’s unclear if she was the sole mastermind behind the whole thing but it is widely believed that she, herself chose who succeeded her. What we do know is she wasn’t left completely empty-handed; she married Izz al-Din Aybak shortly after she handed him power, meaning she retained her position as Sultana albeit now as a consort. As two people who were not of the Ayyubid bloodline, they thus founded the Mamluk dynasty which would remain the leading political power in the Middle East until the emergence of the Ottomans. In order to placate the various parties that opposed her, Aybak announced that he was rule as a representative of the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad (thus pleasing the Caliph and securing his support) and made a number of other concessions in order to please The Ayybuid’s. They were however not satisfied and bloody violence soon kicked off. The Caliph was busy dealing with the Mongols who were causing chaos (as always) so he sought a peaceful solution between the Mamluk’s and the Ayyubids. Through negotiation and mediation (in which Shajar played a key role), an agreement was reached that gave Shajar & Izz al-Din control over southern Palestine (including Gaza & Jerusalem). By this agreement the Mamluks not only added new territories to their dominion but also gained recognition for their new state. For a while peace was achieved however behind closed doors Izz al-Din Aybak was becoming increasingly paranoid, particularly in regards to the Salihiyya Mamluks who were fairly loyal to Shajar and had helped her in installing Izz al-Din. To keep them under control, he had Faris ad-Din Aktai the leader of the Salihiyya Mamluk’s and an ally of Shajar’s assassinated. A significant number of the Salihiyya Mamluk’s then left Egypt and fled to Syria where they joined the Ayyubid al-Nasir Yusuf. The problem with that, was that Shajar was left with very allies still in government, and by 1257 tensions between the married couple was at an all time low. He wanted to be the all-powerful uncontested sovereign however Shajar was still very powerful and very popular and had during her short time as the monarch, managed to a) stop the country from collapsing and b) put a stop to the European Crusaders. This meant she was very well-respected and well, her husband was less respected despite being recognised by the Caliph. It’s clear that when Shajar had chosen him to succeed her, she been under the assumption that he would be content to be a puppet king and that it would be her that would be doing the actual ruling. It didn’t quite turn out that way, and Izz al-Din was clearly not content to be a pawn in a very complicated game of political chess. The two spent pretty much most of his reign in a seemingly never-ending domestic spat over who was actually running the show. It’s believed that Shajar not only kept certain affairs of state from him, but also remained in discreet contact with her former allies who had fled to Syria and apparently tried to stop him from seeing his other wife. It got so bad between them that Izz al-Din Aybak decided to marry the daughter of Badr al-Din Lu’lu the Emir of al-Mosul, in order to secure another ally who could bolster his support. Badr al-Din proved to have a slightly larger number of brain cells than Izz al-Din Aybak and warned him that not only did Shajar have the support of Syria but she was also kinda a force to be reckoned and it was wiser for all involved not to cross her. Did Izz al-Din Aybak listen? Well no, and he most definitely lived to regret it because in 1257 whilst having a nice bath, he was drowned by his servants, having ruled Egypt for just seven years. Shajar, bless her heart, tried to convince everyone that he had died suddenly and tragically and that she was once again a sad, grieving widow. Safe to say no one bought it and the servants who had drowned her husband, confessed that she had ordered his death (admittedly they confessed this under torture so there’s the chance they lied). Shajar and her closest allies were then arrested by Izz al-Din’s men however they refused to execute her after the Salihiyya Mamluk’s demanded she be merely imprisoned – they sent her to live in what was known as the Red Tower. In the aftermath, her step son the 15-year-old Mansur Ali was installed as the new Sultan. He was less forgiving towards his step-mother as was his actual mother who was pretty pissed at being widowed; on the 28th April they ordered she be stripped and beaten to death for the murder of her husband. It’s believed her naked body was then horrifically thrown from the top of the tower and left there for three days until she was finally buried. She was buried at the mausoleum she had herself designed in Cairo near the the mausoleum she’d had constructed for her first husband and the Mosque of Tulum; shortly after her death a mihrab (prayer niche) was commissioned in her honour inside the mosque and is decorated with a mosaic of the “tree of life” (her name means Tree of Pearls). Her mausoleum was the first first funerary complex in this area to be built for a ruler and included a madrasa, a bathhouse, a palace and a garden. Unlike most mausoleums which usually emphasise the rulers lineage, Shajar’s did not (mainly because she had been a slave and thus had no prestigious lineage nor did she have any descendants after her death). Her mausoleum instead became a meeting place for the women of Cairo as well as a shrine to Shajar herself. The mausoleum was just one of the many examples of architecture Shajar had constructed during her tenure as Sultana; when her first husband died she had been responsible for ordering the construction of his mausoleum which she expanded just a few years before her own death. She also ordered the construction of several charity foundations and her architectural designs were used as the foundation of Mamluk architecture with the Mamluk sultan’s that followed adopting many of the hallmarks of her building works. She’s remembered nowadays as the first & only female monarch of an Islamic Egypt.

Theodelinda (sometimes spelt Thedelinde) was born around 570AD the daughter of Garibald I Duke/King of Bavaria and Waldrada; on her mother’s side she was descended from the previous Lombard king Waco whose family had ruled for at least seven generations. Theodelinda was a teenager when in 588 she was married to Authari the King of the Lombards and son of King Cleph. One very enthusiastic supporter of the marriage was Pope Gregory I who had a track record of trying to arrange marriages between a Catholic kingdom and a non-Catholic kingdom (he had previously encouraged the marriage between the French princess Bertha aka granddaughter of Clovis I and the Kentish princess Aethelbehrt). As King of the Lombards, Authari was of the Arian faith. Theodelinda and Authari’s marriage was brief as he died in 590 and little is known about their relationship. What we do know is that Theodelinda was very well regarded and so well-esteemed by the people of the Lombard kingdom that they basically asked her to remain in power and choose her husband’s successor. Great for Theodelinda but I do questioned the wisdom of allowing a 20-year-old to choose the next King. She settled on Agilulf the Duke of Turin and a relative of her late husband. Their marriage was seemingly a happy one (we think); at the bare minimum they proved to be a pretty good political team. Although he retained his Arian faith, he allowed his children with Theodelinda (including his son & heir) to be baptised a Catholic and he allowed Theodelinda to exert significant influence in restoring Nicene Christianity to supremacy in Italy at the expense of his own faith. This didn’t go down particularly well with the dukes of his realm who were convinced he had consigned himself to Nicene Christianity and was allowing Theodelinda too much influence. She frequently corresponded with Pope Gregory who was an enthusiastic supporter of her quest to spread their brand of Catholicism. In 616 Agilulf died and he named Theodelinda regent for their son Adaloald who was still a child. Even after her son came of age to rule in his own right, he allowed his mothers influence and she continued as co-ruler over the kingdom. Due to her religious beliefs and policies, she came into conflict with some of the kingdom’s nobles but was pretty well respected throughout the thirty five years she was Queen. During her tenure she constructed a Catholic cathedral dedicated to St John the Baptist near Milan and also established a number of Catholic monasteries. In the early 620’s her son began showing signs of mental instability; by 626 the nobles had, had enough and staged a coup to remove him from power. Theodelinda’s involvement is unknown however the fact his successor Ariobald was also Theodelinda’s son in law (he was married to her daughter Gundaberga) means it’s possible Theodelinda sanctioned or agreed to her son’s deposition. Oddly though Ariobald was hostile to the Catholic faith; it’d be surprising if she agreed to the new Lombard ruler being an open opponent to the religion she was so devoted to. Having said that Ariobald was the only option for the throne that meant her family stayed in power, as she had no other sons. Theodelinda died in 628. Eight years later her son in law died and with no son to succeed him, Rothari the son of the Duke of Brescia was elected King of the Lombards. In an interesting twist of fate he then married Ariobald’s widow and Theodelinda’s daughter Gundaberga. One of the reasons Rothari was chosen was that unlike his predecessor, he was tolerant of Catholic’s. Whether Gundaberga played any role in his election is unknown. Like mother like daughter maybe?