With the recent news that Camilla the Duchess of Cornwall is going to be Queen Consort when Charles eventually becomes King (if you recall, it was previously stated she would be Princess Consort instead), I’ve seen lots of discussions of her role as a royal mistress (some of which is just flat out slut-shaming) and the comparisons to royal mistresses of bygone eras. Now whilst I don’t condone some of her life choices, being a royal mistress is an occupation as old as time and there have been some truly fascinating women that have served in that role. The position of royal mistress is such an interesting one; most royal marriages in history are politically arranged with personalities, temperaments and personal desires utterly ignored. The mistress however is the king’s choice, and the most interesting royal mistresses are the ones that not only manage to get the kings attention but keep it. Those mistresses are rare. Even rarer are the women that go from mistress to wife, Camilla obviously being one of them. I realised, whilst reading some of the recent discourse about Camilla, that quite a few of my favourite women in history came to prominence as the paramours of men that wear a crown, so I thought I’d put together a short-ish blog post with just a few of my favourite royal mistresses. There are a couple who I’ve already mentioned before on this blog such as Catherine I of Russia; due to that I won’t be mentioning her in this post because you can go look at my previous mention of her here. Enjoy!

First on my list of most fabulous mistresses is Barbara Palmer (better known by her maiden name Barbara Villiers) the Duchess of Cleveland & Countess of Castlemaine who was the most infamous, most powerful, most feared and most scandalous mistress of Charles II King of England’s rather extensive list of mistresses. Born into the aristocratic yet impoverished Villiers family, she was a relative of the 1st Duke of Buckingham (aka the notorious favourite & possible lover of James I who was Charles II’s grandpa) and the daughter of a man that bankrupted himself by financing a regiment to fight on the side of the King during the Civil War. Unfortunately for all involved, he died in said war, leaving his widow and daughter with very little. After the execution of Charles I, the family remained loyal to the crown albeit secretly and every year on the 29th May (the birthday of the new king) they clandestinely toasted to his health and prosperity. The new King may I point out was across the English Channel living in The Hague. Now Barbara despite her lack of money had a number of trump cards up her sleeves, the first of which was that she was a bona fide babe and was considered one of the pre-eminent beauties of the Restoration period. She was tall and voluptuous with masses of dark hair, pale porcelain skin and Elizabeth Taylor esque violet eyes, a winning combo that combined with her fiery temper and overt sensuality evidently got men’s attention and she had a number of lovers before marrying Roger Palmer (later the Earl of Castlemaine). Now Barbz over here was to put it mildly tempestuous and his family were convinced she would ruin his life with his father going as far as to predict she would make him the most miserable man alive. Shortly after their marriage the newlyweds travelled to the continent to pledge their allegiance to the new King as part of his court; this was when she met Charles for the first time and in no time at all he was unsurprisingly besotted. As a side note this does make Barbara slightly different from the other women I’ve put in this post; most of them became the mistresses of an established King. Charles was not at this point King and to be honest it wasn’t 100% guaranteed that he ever would be. He did however manage to win back the throne and was crowned on 29th May 1660. Barbara was present and it was later alleged that they conceived their first child together the night before the coronation (although how anyone would know this for certain I have no idea). During her tenure as mistress, she gave birth to six children; three daughters Anne, Charlotte and Barbara and three sons Charles, Henry and George, all of whom were given the surname Fitzroy (meaning son of the King). There are however some questions as to the paternity of the eldest and the youngest; the eldest Anne was awkwardly claimed by both the King and Barbara’s cuckolded husband whilst others noted she bore a resemblance to one of Barbara’s other lovers the Earl of Chesterfield. The youngest another daughter Barbara was born as the relationship with the King was coming to an end and although he publicly acknowledged her as his, behind closed doors he was fairly certain she wasn’t. Barbara’s husband allegedly thought she was his and when he died she inherited his estate whilst the Earl of Chesterfield was once again also rumoured to be a potential papa. It’s most likely that Barbara’s cousin John Churchill later the Duke of Marlborough was actually the father. As you might be able to tell, Barbara was pretty comfortable in her sexuality and had a number of lovers, outside of her relationship with Charles, a fact he was more than aware of. She would go on to be his undisputed favourite for over a decade and in that time became known as “The Uncrowned Queen” whilst John Evelyn called her the “Curse of the Nation”, the latter nickname of which is frankly a level of notoriety we should all aspire to. Barbara’s level of notoriety was the result of a number of factors; firstly she was a very public royal mistress, even more publicly visible than his queen Catherine of Braganza, secondly was her lack of fidelity to the king which was a big no no (especially as she allegedly slept with his grown up son), thirdly she was a notorious spendthrift who had, to put it mildly extravagant tastes, and fourthly it was a very well known fact that Barbara had a TERRIFYING temper, and that Charles often gave her what she wanted purely to avoid her theatrics. Honestly the sheer level of anecdotes of Barbara kicking off is impressive. Now Barbara was not one of those mistresses who kept away from politics; she worked with the group of men that became known as the Cabal Ministry to bring about the downfall of Charles’ main advisor Clarendon, publicly mocking him when he was dismissed. Although not as politically influential as some royal mistresses (*cough* Madame Pomapdour *cough*), she clearly had some sway. Now after over a decade her relationship with Charles came to an end in around 1673 and in 1676 the Duchess travelled to Paris with her four youngest children. In France she was as charming as ever although returned to England in 1680. Her extravagant tastes didn’t lessen with time, and between 1682 and 1683 she had Nonsuch Palace (the palace that Charles had gifted her in 1670) pulled down and had the building materials sold off to pay her extremely high gambling debts. She at some point reconciled with the King and she was with him in the week leading up to his death in February 1685. Although she had not been in his favourite in over a decade at the point that he died, Charles’ death did have somewhat of an impact. For starters she could no longer appeal to his generosity, and after she death she began a relationship with an actor of terrible repute, giving birth to his child in March 1686. In the years afterwards she wasn’t a particularly visible figure in society. In 1705 her husband died, and she soon after married a major general, who was to put it mildly a massive money grabbing twat who was later prosecuted for bigamy after it was discovered that he had married a young lady by the name of Mary Wadsworth, in the mistaken belief that she was an heiress, just two weeks before he married Barbara. Barbara’s glittering life came to an end on the 9th October 1709 at the age of 68.

Even if you haven’t studied French history or are as obsessed with royal women as me, you’ve probably heard of Madame de Pompadour. Especially if you happen to be a Doctor Who fan. Now Madame de Pompadour was very much a real woman, and quite an extraordinary one. Born Jeanne Antoinette Poisson in Paris in 1721 the daughter of Francois Poisson and Madeleine de la Motte; there were however questions about the paternity of Jeanne with speculation rampant that her biological father was either the rich financier Jean Pâris de Monmartel or Charles François Paul Le Normant de Tournehem. In 1725 when little Jeanne was four, her father found himself in a heap of legal trouble and was forced to flee the country or risk imprisonment and potentially death. Le Normant de Tournehem (aka one of her potential fathers) became her legal guardian and ensured that she had the finest education possible; she was taught dancing, drawing, painting, engraving, theatre, the arts and literature. She grew into a charming, polished and culture young woman albeit one with a sometimes shaky health; she also grew to be beautiful with a capital B. A famous anecdote tells the story that as a child, her mother took her to a clairvoyant who told her that she would one day reign over the heart of a king. Her family took that literally and from that moment on she was given the nickname “”Reinette” meaning little queen. When she was 19, her guardian le Normant de Tournehem arranged for her to marry his nephew Charles Guillaume le Normant d’Etiolles; once the pair were married he disinherited all his other nieces and nephews and made Charles and Jeanne his sole heirs. Charles unsurprisingly fell head over heels in love with his new wife and she told him she would never leave him…..unless of course the king wanted her. Awkward. Now Jeanne soon became a celebrated member of Parisian society, frequenting various prominent salons where she rubbed shoulders with some of the most prominent titans of the Enlightenment such as Voltaire, Montesquieu and Helvetius, all of whom found her delightful. Her reputation increased and it’s fairly certain that by by 1742 the king Louis XV had probably heard of her beauty and grace which was practically legendary in Paris. It wasn’t until 1744 however that the two met, with their first acquittance allegedly taking place in the forest of Sénart where the king loved to hunt; Jeanne occupied an estate nearby. It’s unlikely the meeting was accidental especially as she was dressed strikingly in a candy pink dress sitting in a baby blue phaeton (which is an open top carriage sort of thing). Basically she was dressed like a beautiful pink macaroon. Think Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette but with a slightly different silhouette and more frills. She was clearly trying to win his attention and boy did she. It wasn’t until December however when his then mistress Madame de Chateauroux died that the King made his move (interesting fact – Madame de Chateauroux was one of the Mailly sisters, four out of five of whom were mistresses to the king at one point or another!!). In February 1745 to celebrate the marriage of his son to a Spanish princess he threw a magnificent masquerade ball (like only a Bourbon king can) and issued Jeanne with an invite. She came dressed as the Roman goddess Diana the Huntress a clear reference to their first meeting in the forest. The King was oddly dressed as a yew tree and spent the entire night hovering around Jeanne until he rather publicly unmasked himself and declared his affection for her in front of EVERYONE. Now Jeanne was not willing to just be a mere mistress, she wanted clarity on her role in his life and she wanted it asap. Louis was completely and utterly fixated and so immediately named her his official mistress and granted her incredible apartments above his. To top it off he arranged per her request, a legal separation from her very heartbroken husband who was by all accounts very weepy (even though she had kinda given him a heads up) and even fainted at the news. Jeanne’s new-found role as the king’s one and only, unsurprisingly led to gossip galore at court, especially when you consider the fact that Jeanne was not from the nobility (gasp) and was intimate friends with atheists like Voltaire. The blue blooded very Catholic court of Versailles was shocked and appalled however Louis, was visibly pissed at anyone who demonstrated even the smallest bit of disapproval towards his new mistress. In order to make things a little easier he made her the Marquise de Pompadour which gave her wealth, an estate and a title and thus a little more acceptable to everyone at Versailles. Now Pompadour was nothing if not intelligent and she recognised that it was probably best not to alienate the Queen Marie Leszczynska; the two woman surprisingly developed a pretty good relationship and Jeanne was always careful to demonstrate her respect for the woman who wore the crown (unlike some royal mistresses *cough* Montespan *cough*). The Queen would later admit to preferring Jeanne over all of the king’s other mistresses. The thing is, Jeanne did not find being a mistress particularly easy; as I mentioned her health was delicate and she suffered from recurring colds, headaches, bronchitis, hemoptysis (coughing up blood) and three miscarriages. Some of this stemmed from a horrific case of whopping cough in her youth. Her health only worsened over time which had a negative impact on a rather vital aspect of being a royal mistress – sex. She struggled physically to perform and would admit that she didn’t even enjoy sex; she was deemed to have “cold blood” the cure for which they thought in those days was a diet of hot chocolate laced with vanilla and amber, truffles and celery soup. Evidently it didn’t work and by 1751 the sexual relationship between the two was over. Jeanne however managed to do what most mistresses cannot; she made herself invaluable to him outside of the bedroom, and he came to see her as the only person he truly trusted and the only one that would give him the unvarnished truth. She ended up wielding huge amounts of power at court, and in October 1752 was elevated to the role of Duchess, and in 1756 to the role of lady-in-waiting to the Queen, the most noble rank possible for a woman at court. She basically managed to charm her way into the role of prime minister, becoming responsible for appointing government ministers, firing government ministers and dictating domestic and foreign policy. She and her protégée the Duc de Choiseul were partially responsible for the new found alliance between France and it’s old enemy Austria. Under these new alliances, the Seven Years War kicked off which saw France, Austria and Russia against Britain and Prussia. The alliance between France, Austria and Russia became known as the League of the Petticoats because all three were being led by a woman – Jeanne was running the show in France, Austria was ruled by Empress Maria Theresa and Russia had Empress Elizabeth I on the throne. The Seven Years War from a French perspective was lets be honest an absolute clusterfuck and one of Louis XV’s most questionable decisions (and he made a few). She was also a famed arts patron spending exorbitant amounts of money on art, architecture and fashion; she was the patron of the likes of Jean-Marc Nattier, François Boucher, Jean-Baptiste Révellion and François Hubert Drouais and as Elizabeth Abbott writes in reference to the Rococo era, “the style she imposed on France was so unerringly brilliant that she defines an entire aesthetic era”. Despite her best efforts she remained very unpopular amongst courtiers who were appalled that the king would compromise himself with a commoner. Jeanne it would appear was actually pretty sensitive to the non stop rumours spread about her and was known to frequently push for Louis to take punitive action against her enemies. She remained an all mighty figure at court whilst Louis remained devoted and he was by her side when she died from tuberculosis in 1764 at the age of forty-two. He had in fact nursed her throughout her illness which is kinda cute. She would end up being the second to last of his official mistresses with only Madame du Barry following her (and we all know how that ended).

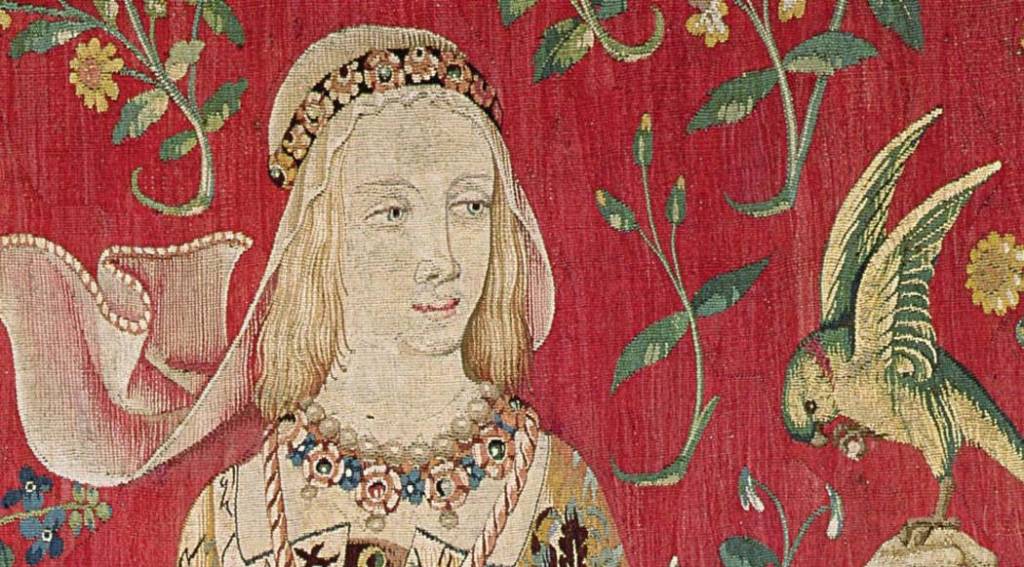

Francoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart was born in 1640 the daughter of Gabriel de Rochechouart the Duc de Mortemart and Diane de Grandseigne. Now unlike Pompadour who had more modest origins, Athenais, possessed the blood of two of France’s most ancient noble families and her lineage went back further than anyones (I mean we’re talking over a thousand years here). Not only had her mother served as Lady in Waiting to the Queen Consort then Queen Regent/Queen Mother of France Anne of Austria but her father had been a childhood companion of and later First Gentleman of the Bedchamber to Louis XIII as well as a confidante of both the aforementioned Anne of Austria and Cardinal Richelieu (who throughout Louis XIII’s reign pretty much ran the country) whilst her elder siblings Louis Victor and Gabrielle were childhood companions of the young Louis XIV. She was basically as blue blooded as they come, with exemplary royal connections. Educated at the Convent of St Mary in Saintes, Athenais grew to be a young woman of exceptional beauty with corn-coloured blonde hair, large blue eyes, pale skin and a curvy yet petite figure. She was also considered to be clever, sharp, amusing and possessing of a very sharp tongue, in fact her entire family were renowned for their famous Mortemart wit. In 1660 at the age of 20 she became a lady in waiting to the King’s sister in law Henrietta Anne of England the Duchess of Orleans. Three years later she was married off to Louis Henri de Pardaillan de Gondrin the Marquis de Montespan. Rumours abounded that he had not been her first choice however the man she desired had been forced to flee the country. Now as the Marquise de Montespan (as history would mostly know her), she continued serving the Duchess of Orleans and soon became considered one of the reigning beauties of court. She was well educated and cultured and her in-depth knowledge of politics and literature won her acclaim. She was also heavily courted by the men of Versailles. Alongside her sister Gabrielle and her brother Louis Victor, both of whom were as beautiful, intelligent and ruthless as her, she formed a renowned faction at court that was increasingly influential. By 1666 Montespan was beginning to challenge the King’s long term mistress Louise de la Valliere; awkwardly both de la Valliere and the Spanish-born Queen Maria Theresa completely underestimated the younger woman and didn’t consider her a rival, which I have no doubt spurred the very ambitious and slightly vindictive Montespan on even more. By 1668 Louise was no longer top dog and had been relegated to second place behind Montespan; the two women had connecting bedrooms so the King could visit Montespan without the rest of court knowing. Eventually Louise joined a convent and left court, leaving Montespan as the King’s undisputed favourite. She gave birth to her and the King’s first child – a little girl Louise Françoise – in 1669 (she already had two young children with her husband). Although the girl did not live long, Montespan and the King went on to have six more children between 1670 and 1678; three sons Louis-Auguste the Duke of Maine, Louis-Cesar the Count of Vexin and Louise-Alexandre the Count of Toulouse, and three daughters Louise-Françoise the Princess of Conde, Louise-Anne Marie Mademoiselle de Tours and Françoise Marie the Duchess of Orleans. In 1673 in an act that was almost unprecedented, her children with the King were legitimated and given the royal surname of Bourbon; in later years this secured the girls advantageous marriages and the boys high ranking positions, wealth and titles. Now unlike many mistresses who were usually unmarried or widowed or married specifically to a man who didn’t mind their wife sleeping with the King, Montespan was married, and not only was she married but she was married to a man who was most definitely not accepting of his wife’s infidelity. Her husband raised an absolutely stink at court, at one point allegedly challenging the King at Saint-Germain-en-Laye to a duel. He also in a less than subtle manner had his carriage and gates decorated with antlers (symbolising horns, a traditional symbol of the cuckolded husband). Montespan was to put it mildly mortified and the King was increasingly irritated by his mistresses sulking husband. Montespan’s husband was for a while imprisoned although eventually released and exiled to his lands. You’d think imprisonment would shut a guy up but noooooo this man was not willing to back down and between 1670 and 1686 he went to Paris every year to protest his wife’s infidelity. He also, and this quite frankly is insane, declared that she was dead to him and commanded an annual requiem mass to be sung for her (despite her being very much alive and living it up in Versailles) during her lifetime. He then forced their two young children to attend a funeral for their ‘dead’ mother. The unhappily married couple were granted an official separation in 1674 (this was most certainly the King’s doing) however opposition to the relationship did not end there. Not only did her husband object to her and the King’s adultery, the Catholic Church did too and they were very vocal about it. In 1675 a priest refused to give her absolution, something that was necessary for her to take Easter communion, a requisite for all Catholics. He allegedly said something to the effect of “is this the Madame that scandalises all of France? Go abandon your shocking life and then come throw yourself at the feet of the ministers of Jesus Christ”. Safe to say neither Montespan nor the King were particularly happy and although the King appealed to the priest’s superiors, the church refused to accept the affair. The church’s disapproval didn’t particularly seem to have much of an effect on the affair which lasted around fifteen years; those fifteen years would be the most glorious of Louis’ reign and she would go on to be the most celebrated of all his mistresses. She was widely acknowledged as the real Queen of France during her time and she definitely acted as such; she was extravagant and demanding and she was charismatic enough/Louis was besotted enough for her to get exactly what she wanted. Money was no object. Her apartments at Versailles were known to be lavish and she was spoilt with a never ending stream of gifts (usually jewels, flowers & animals). She was given the nickname “Quanto” meaning how much in Italian, not that anyone would dared have called her that to her face. They were far too scared of her. As I mentioned she was known for her sharp tongue and her brutal honesty; as Nancy Mitford wrote in her biography of Louis XIV, “both she and the King frightened people; she was a tease, a mocking-bird, noted for her wonderful imitations and said to be hard-hearted. This meant that she regarded serious events with a cheerful realism; she was not sentimental”. She also despised the Queen and unlike other royal mistresses made absolutely no effort to hide her feelings, in fact she was downright rude. The feelings were very much mutual with Saint Simon writing, “The Queen was finding more and more difficult to bear Montespan’s haughty behaviour, much different from the deeply affected respect that la Valliere had for her, et whom she loved very dearly, when she [Maria Theresa] was often sighing “Cette pure me fear mourir! / This bitch will be the death of me!”. Whilst perhaps less overtly political than Pompadour, she demonstrated a significant influence during her tenure as mistress; she openly favoured Colbert, supplanted the Queen during meetings with ambassadors where she charmed them with her famous wit, supported the intellectual awakening of court, was a generous patron of the arts and letters forming relationships with the likes of Corneille, Racine and La Fontaine and initially tried to prevent the war with Holland however when war did eventually break up she armed her own military ship. She also became one of the public faces of the monarchy with Antonia Fraser writing, “the public face of Athénaïs was now as the dazzling creature, the brightest star in the galaxy which surrounded the Sun King, the one for whom, without knowing it, he had always craved to complete his image in the world at large (if not the world of the Catholic Church)”. The Affaire des Poisons (a major political scandal which lasted from 1677 to 1682) would bring about the end of Montespan’s reign; the scandal involved a number of prominent members of the aristocracy being implicated and sentenced on charges of poisoning and witchcraft with accusations of black masses. The scandal reached into the inner circle of the king and led to the execution of 36 people. Some of those executed had ties to Montespan which caused all sorts of problems. Accusations were thrown that Montespan had not only attended the black masses but that she had used witchcraft to keep Louis in love with her and that she had poisoned Marie Angélique de Scorailles, a young rival for the King’s affection. She was never charged with any crime and it’s highly unlikely she was involved. She was however a very powerful woman with lots of very powerful enemies and accusing a woman of witchcraft (as pretty much every part of history will show you) is a sure fire way to ruin her reputation. Two of the King’s closest advisors Louvois and Colbert, the latter of whom Montespan had once been a key supporter of, helped keep the accusations hush hush in order to protect Montespan and her children. Louis didn’t end the relationship immediately but it was certainly the beginning of the end and by 1691, no longer in royal favour, she left court and retired to the Filles de Saint Joseph convent in Paris where she dedicated herself to charity, giving vast sums to hospitals and orphanages. She remained there until her death in 1707. Louis meanwhile took Francoise d’Aubigne the Marquise de Maintenon as a mistress (although she refused to conduct a physical relationship with him whilst his wife was still alive); awkwardly Maintenon had once been a close friend of Montespan’s and had been in charge of raising Montespan and the King’s children. A strongly religious person, Maintenon encouraged Louis to become more devout; he no longer took mistresses and banned operas during Lent. Once a controversial figure at court, Montespan would later be missed by those who had once loathed her and they lamented that Versailles was no longer as fun as it had been during her reign.

There are very few male historical figures I truly adore; most of my favourites as I’m sure those of you who have read this blog/looked at my Instagram will know, are women. There are however a few male historical figures that I enjoy immensely and one of those is Francis I King of France. Now there are a ton of reasons why I love him but one of the main reasons is that he seems to have a real genuine respect for women’s intellect. He once commented “une cour sans femmes est comme un jardin sans fleurs” (“a court without women is like a garden without flowers” and throughout his reign his mother Louise of Savoy and sister Marguerite of Navarre were the two most prominent politicians at his court particularly in the first half of his reign. Who may you ask was top dog in the second half of his reign? It was this woman Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly. Now Anne was born in 1508 somewhere in Picardy the daughter of Guillaume de Pisseleu seigneur d’Heilly a low ranking noblemen with very little wealth and status. Now Anne grew up in a big family, and by big I mean huge; her father was married and widowed multiple times (Anne’s mother was wife number 2) and it’s believed Anne was one of 23 children (although I’ve seen some chroniclers suggest even higher figures!!). Despite their lack of wealth, Anne’s step-mother Madeleine of Laval made sure her step-children were given an excellent education which focused on the arts, sciences and literature and included all-important court etiquette. This would come in very handy when at some point in her teens probably between 1520 and 1522 when she was 12-14 she became a Maid of Honour to Marie of Luxembourg Countess of Vendôme. This meant coming to court and it was during this time she made quite the impression on none other than Louise of Savoy, the King’s Mother and the most formidable woman at court. Now Francis was at this point married to his cousin Claude of France however it was not a marriage of great passion; although Francis respected Claude, held great fondness for her and the two went on to have seven children altogether, it had been a purely political match. His favoured mistress since 1518 had been Francoise de Foix the Countess of Chateaubriant; tall, dark-haired and cultured, Francoise had initially played hard to get however she had eventually acquiesced and had been his official mistress ever since, a fact that the King’s mother Louise of Savoy was less than happy about. She did not like Francoise at all, in fact she loathed the entire de Foix family and would gladly have seen the back of them; the only thing she did approve of as far as the affair was concerned, was Francoise de Foix’s lack of political involvement. Francis kept her away from power and politics and she held very little influence over him; in fact the only time she seems to have got involved was when she asked Francis not to be pissed at her brother after a battle went awry. Whilst Louise of Savoy did not like Francoise de Foix, she did grow rather fond of Anne and after a period of time in the service of Marie of Luxembourg Countess of Vendome, Anne was transferred to Louise of Savoy’s service. This happened whilst Francis was abroad fighting the Spanish in the Italian Wars so probably around 1525-1526. The Italian Wars were somewhat of a disaster for Francis especially in 1525 when during the Battle of Pavia he was captured and then taken to Madrid where he was held hostage. A kingdom without a king is to put it mildly, in a bit of a pickle and the country looked to Louise of Savoy to lead the country in Francis’ absence. Anne would have been by Louise’s side the entire time and it’s likely she learnt a thing or two from a woman who was one of the best female politicians France has ever seen. Francis eventually returned to France in 1526 and when Louise of Savoy went to meet him, she had Anne accompany her. Francis it’s said was besotted instantly and it’s not hard to see why; Anne was intelligent, witty, cultured, very beautiful (we know she was a blonde in contrast to the very dark brunette that was Francoise de Foix) and became known as “the the most beautiful among the learned and the most learned among the beautiful”. They shared a love of art and literature and Francis always fond of a woman with great wit was taken with how sharp Anne was. Before long Anne had replaced Francoise as his official mistress; Francoise remained at court for a little while longer hoping he would tire of Anne and return to her. That didn’t happen and so she retired from court in 1528-1529. Now we don’t know that much about Anne’s early years as mistress; the English envoy Anthony Brown wrote in 1527 that Francis clearly favoured her above all others and wasn’t particularly subtle about it, even going as far as to wear her colours, an official proclamation of her importance. It wasn’t until the 1530’s she began to emerge as quite the powerhouse. In 1531 Francis was forced to marry Eleanor of Austria the sister of the Holy Roman Emperor/King of Spain Charles V as part of a peace treaty (Francis’ first wife Claude had died in 1524). There was a bit of controversy when poor Eleanor entered Paris and Francis decided to watch from a window with Anne displayed besides him; his decision to do so according to Francis Bryan an English envoy shocked onlookers. Not only did Anne become far more visible in the 1530’s but she also became far more politically influential. I do think it’s interesting that the emergence of Anne as a political powerhouse coincided with the death of Francis’ mother Louise of Savoy in 1531. In many ways Anne stepped into her shoes, taking her place as Francis’ most trusted advisor. She also developed a good relationship with his sister Marguerite who would later dedicate some of her writing to Anne describing her as “a sun midst stars who spares nothing for her friends nor stoops to vengeance on her foes”; the two often shared tactical objectives in politics especially in regards to religion and whilst Marguerite was known to be notoriously blunt and waspish about those in her brother’s inner circle, frequently denigrating them to ambassadors, she never spoke ill of Anne. In order to give Anne an official position at court, Francis first named her governess to his daughters (Anne it’s believed was very close with his girls and had quite good relations with his eldest son Francis and youngest son Charles although had a poor relationship with his second son Henry) and then in 1534 married her to Jean IV de Brosse who he created Duke of Etampes. Now a duchess Anne was one of the highest ranking women in court. Throughout the 1530’s her influence grew and by 1540 Anne was all powerful at court with the imperial ambassador writing in 1541 that “no councillor dared approach the King about anything without checking first with Madame d’Etampes if she approved it” whilst during a war campaign in 1542 dispatches from the frontlines in Flanders were forwarded to her at Lyon rather than the King who was with the bulk of the army in Languedoc. Another instance of her significant influence was when Francis’ poor neglected wife Eleanor tried to salvage the peace between her brother Charles V and Francis. She acknowledged Anne’s importance and advised her very unimpressed brother that if he wanted to win Francis over, he needed to get Anne on side. Charles was said to be very unimpressed at the idea but listened to his sister anyway and presented Anne with a significant number of gifts. Now with growing power comes an increasing number of enemies and throughout the mid-late 1530’s Anne began to clash with some of Francis’ other advisors particularly in regards to religion (some were staunch Catholics whereas Anne was not and fiercely advocated for tolerance to Protestants; in her later years she would actually end up converting herself). One of her staunchest enemies was the Duke of Montmorency who at one point had been Francis’ most trusted friend and advisor; by 1540 he was disgraced and banished from court. Anne was widely considered to have been the instigator of his downfall which coincided with the return to prominence of Admiral de Brion a political rival of Montmorency’s who had fallen out of favour in 1536. Anne and Brion became political besties and with Montmorency’s fall from grace, Brion was restored to favour. His nephew also married Anne’s sister to secure their alliance. Other influential advisors such as Claude d’Annebault and Cardinal du Bellay also owed their prominence to her favour; she was also said to be the reason for Francis’ increasing appearance at council meetings with him attending them far more frequently towards the end of his reign than at the beginning. Robert Knecht implied that may have had something to do with the fact that according to the imperial ambassador “Anne was the real president of the King’s most private and intimate council”. One person Anne did not get along with was Francis second son Henry. He had been the Duke of Orleans until his elder brothers death in 1536 had made him the heir to the throne. Henry’s relationship with Francis was not a particularly good one, however he was close to Montmorency and was infuriated with his fall from grace. The fact that Henry’s mistress Diane de Poitiers and Anne had hated each other for years added to his contempt for his father’s mistress. In 1544 Diane was dismissed from court by Francis allegedly on Anne’s insistence leading to a further deterioration in the relationship between father and son (in the midst of all this was Catherine de Medici who managed to play nice with all sides and survive the whole bloody lot of them). Back in 1528 Francoise de Foix had declared that Francis would eventually tire of Anne; he never did and when he died in 1547 she had been his mistress for 21 years and his closest and most influential advisor for around 15 of those years. Without Francis to protect her however, she was at the mercy of Henry, Diane and Montmorency, three of the people who hated her most. She was stripped of the titles, lands and many gifts that Francis had granted her in their time together and forced into retirement far from court. The initial years of life without Francis were rocky to say the least; she was at one point accused of heresy although Henry eventually chose not to pursue that charge whilst she was also briefly put under house arrest by her husband who seemed to have a delayed reaction to her infidelity and accused her of disgracing his family name with her conduct. He wouldn’t have dared reproach her for infidelity before Francis’ death but with her royal lover gone, she had no protection. Luckily for her her husband died in 1564 and the last 15 or so years of her life were rather peaceful. She was an intelligent woman and despite Henry stripping her of multiple estates and palaces given to her by Francis, she still owned signifiant properties in Paris which she rented bringing in an impressive income. She ended up a very wealthy women and with no children of her own, made sure her nieces and nephews were well looked after. She arranged good marriages for them, paying for the weddings and providing dowries including the dowry for her beloved niece Diane de Barbancon when she married the Baron de Fontenay in 1560. She also as I mentioned later converted to Protestantism although did so discreetly and would end up becoming well respected within the Protestant community. She outlived Henry, Diane and Montmorency, dying in 1580. Her death caused a furore in her family as they all fought over her fortune. French mistresses are lets be honest the most famous royal mistresses in the world and yet I really do think Anne get’s overlooked when in reality she was the prototype for the political mistress. Before her royal mistresses had, had very little political influence. She was able to wield influence in a way that no other mistress had and every mistresses that came afterwards (Gabrielle d’Estrees, Madame de Pompadour & Madame de Montespan etc) should thank their lucky stars for Anne de Pisseleu d’Heilly.

Camilla as I noted is part of a small club of royal women that went from mistress to wife and another member of that club is none other than this woman Katherine Swynford. Not only did she and her lover John of Gaunt marry despite immense disapproval and controversy but through their illegitimate children they also founded a dynasty that would later wear a crown. Take notes ladies. Katherine Swynford was born circa 1350 the daughter of Sir Gilles de Roet a knight that probably came to England in 1328 when Philippa of Hainaut married Edward III King of England (the historical county of Hainaut now straddles the French-Belgium border). It’s been suggested that Katherine was born on the 25th November which is the Feast Day of St Catherine of Alexandria; Katherine wasn’t a particularly popular name in Hainaut and she would later demonstrate an affinity for that particular saint. Now there’s some debate about Katherine’s family background in particular whether or not her family were aristocratic or common folk; it’s been suggested that her father was a descendant of a collateral branch of the Lords of Roeulx however it’s also possible that she had no great ancestry and was essentially a commoner (the Alison Weir book on Katherine has a good section that explores Katherine’s possible family background). Her mother’s name and background are unknown but it’s likely her mother was also from Hainaut although there is a small chance her mother was English. After her father arrived in England in 1328, he remained there for a good number of years, serving the royal court; he served as the Guyenne King of Arms and in 1347 was sent to the siege of Calais where he conducted service on behalf of the Queen. In 1349 he returned to Hainaut, shortly after the Black Death hit England. Katherine’s father had four children overall Katherine, Elizabeth, Philippa and Walter; the latter it’s believed died sometime in the late 1350’s fighting in France whilst Elizabeth became canoness at the Convent of Saint Waltrude Collegiate Church at Mons in Hainaut. Elizabeth and Walter were significantly older than Katherine and Philippa with ten to fifteen years between them, suggesting they may have had different mothers. At some point in the 1350’s Gilles de Roet was sent to serve Margaret the Holy Roman Empress (who was also Philippa of Hainaut’s sister) leaving his younger daughters Katherine and Philippa in Queen Philippa’s care; we can thus infer that their mother was probably dead by this point. Raised under Queen Philippa’s aegis the girls were well educated and it’s possible that the Queen was quite fond of them; after all when Katherine was young (between the ages of 12 and 14), she was married to Sir Hugh Swynford lord of the manor of Kettlethorpe in Lincolnshire; the marriage was advantageous for Katherine who was potentially of common stock and it’s very possible that Queen Philippa arranged the match. Now Hugh at the time of the marriage was a knight in the service of none other than John of Gaunt, Queen Philippa’s third son. We have no idea when Katherine and John first met; she may have known him as a child (it depends on how much involvement Queen Philippa had in Katherine’s upbringing) or they may first have met upon Katherine’s marriage to Hugh in 1366. It’s likely that around the time of her marriage, Katherine entered the service of Blanche of Lancaster who was the Duchess of Lancaster & John of Gaunt’s wife (they had married in 1359 when they were both teenagers). Now Blanche was the daughter of Henry Grosmont the Duke of Lancaster and after the death of her sister Maud in 1362, she had become his sole heiress. This meant that when her father died, she inherited one of the largest fortunes in the country however due to the patriarchal politics of the period, all of it went to John instead. The Lancaster inheritance combined with his own royal inheritance made him the largest landowner in the country (owning land in pretty much every county in England) and the richest man in England. It also gave him ownership of at least 30 castles across England and France and gave him a household of considerable size, comparable to the household of his own father King Edward III. With land, money and castles, comes power and John of Gaunt had more than pretty much everyone else, bar his elder brother Edward and his father the King. Blanche and John’s marriage was by all accounts a happy one and is generally considered to have been a political match that turned into a love match. There is evidence that in the aftermath of her wedding and her entrance into the Lancaster household, Katherine grew rather close with Blanche; not only did Hugh and Katherine name their eldest daughter after the Duchess but both Blanche and John served as godparents to the baby and then had her placed in the royal nursery with their own daughters Philippa and Elizabeth. Blanche of Lancaster unfortunately did not last long dying in 1368, likely from either the plague or childbirth complications; I would personally say it’s more likely to be childbirth complications based on the dates. Now at this point Katherine probably left the Lancaster household and returned to her husband’s estate Kettlethorpe, however at some point in 1370-1371 she returned and was named by John to be governess to his daughters (throughout her life Katherine would maintain a good relationship with all three of John and Blanche’s children). We don’t know when exactly but around that time Katherine’s husband Hugh died; their youngest child was born in 1369 so it’s likely that he died sometime afterwards. He was almost definitely dead by the time John of Gaunt remarried Constance of Castille in 1371. Now Constance had a rather complex and very dysfunctional family background which included her father given the epithet “Peter the Cruel”, her father siring multiple illegitimate children herself included, arguments with the papacy, accusations of bigamy, her father imprisoning and potentially murdering his wife and a civil war that resulted in her uncle usurping the throne. Unlike his happy marriage to Blanche, John’s marriage to Constance was a purely political one and was based on the very ambitious John using his money, power and prestige as an English prince to win Constance’s throne back from her uncle so that they could be King & Queen of Castille together. There was nothing personal nor romantic in their marriage which is why around the time they became man and wife, he took Katherine as a mistress. Not exactly the best start to a union. Now the question of when Katherine became John’s mistress has been asked a thousand times and really no-one knows. There are three options; either she became his mistress a) before Blanche of Lancaster’s death (very unlikely), b) in between Blanche’s death and John’s remarriage (possible) or c) after he married Constance of Castille (also possible). My personal take is that the affair probably didn’t begin until after Katherine’s husband had died in 1371. Katherine throughout her life demonstrated that she was genuinely religious and I don’t think she would have committed adultery whilst her husband was still alive. Also in the 1390’s John told the Pope that they had never committed adultery whilst Blanche or Hugh had been alive; I suppose it’s possible he lied but lying to God’s representative on Earth in the 14th century was a fairly big no no. That doesn’t mean there wasn’t feelings or chemistry or any thing like that between John and Katherine, but I’m fairly certain she didn’t officially become his mistress until after she was a widow. In the novel “Katherine” by Anya Seton (which is based on Katherine’s life), John begins pursuing her after the death of his first wife but Katherine refuses to sleep with him whilst her own spouse is still alive, and only becomes his mistress after Hugh’s death. That theory, I can totally buy especially as there’s evidence that John first granted her a significant amount of money in 1372; the kind of money you’d only give to someone exceptionally close to you i.e your mistress. After becoming his mistress Katherine was almost constantly by his side (except when he was abroad at war) and between 1373 and 1379 they had four children. Their children were given the surname Beaufort supposedly after the Chateau of Beaufort in France which John had inherited through his grandmother Blanche of Artois. It has thus been inferred by historians over the years that the Chateau of Beaufort was where their first child was born however it’s believed that John had already lost the castle by 1373 (the year their first child was born) so it’s unlikely their children were born there. Their first child was born the same year that John’s wife Constance gave birth to a daughter who awkwardly was named Catherine. Now I would like to think that John didn’t name his wife’s child after his mistress but no one has more audacity than a Plantagenet prince so who knows. In the years afterwards whilst Katherine continued to pop out baby after baby, John’s wife Constance did not and their lack of further children is often blamed on his devotion to his mistress. Despite this John and Katherine were initially fairly discreet about their relationship; although his wife knew, John’s family (including the King) almost certainly knew and it’s likely that whilst most of court knew, the wider public did not. It wasn’t until around 1378 that their relationship became public knowledge; from 1377 onwards the two were openly living together with he and his wife at this point informally separated. It was in the mid 1370’s that John’s political shenanigans began to earn him more public scrutiny and controversy; the increased scrutiny on John came about due to the deteriorating health of his brother, the impending demise of his elderly father and the fact his nephew was still very much a child. John thus became the leading political figure in the country and was tasked with among other things trying to keep the peace between the crown and the Commons. His money, influence and well-established ambition however led to accusations that he intended to take the throne should his father and brother die and his young nephew be left to rule. After the death of his father and brother and the accession of his nephew, John was thus the heir to the throne and to many, a man that close to the crown possessing of as much ambition and wealth as John had, was a recipe for disaster. Certainly John had ambition and to be honest I think he might have made a pretty good king but he was also extremely loyal to England and the crown and I find it very unlikely he ever seriously considered being King of England himself. The accusation however was enough to besmirch his name and throughout the late 1370’s John became increasingly unpopular especially after the deaths of his father and brother which forced him to become de facto regent (although not officially) on behalf of his nephew. He was thus forced to mediate between all the various factions of court, all of whom wanted different policies but shared one thing; they didn’t particularly like John. By 1380 enemies of John such as Thomas Walsingham had caught wind of John and Katherine’s affair and began ranting and raving about it, chastising John for his sins on a near daily basis. I won’t go into the various political debacles that followed but I will say that things got very bad, very quickly and in 1381 John was one of the principal targets of the Peasants Revolt. His extravangant London residence the Savoy was targeted by angry Londoners who blamed John for the introduction of a fiercely unpopular poll tax; the palace and everything inside it was completely demolished and what could not be smashed or burned was thrown into the river. Neither Katherine nor John were present; Katherine was not in London at the time and was safe and sound probably at Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire. In the aftermath John and Katherine’s relationship bizarrely became the focus of condemnation and it was suggested that God was punishing England because John was committing adultery with Katherine. Katherine and John thus became Public Enemy Number 1 & 2 and Katherine’s reputation was utterly shattered with the likes of Thomas Walsingham referring to her by every slut shaming epithet under the sun. John’s popularity too was at rock bottom and so out of political necessity as well as a desire to keep her and their children safe (some of John’s staff had been killed at the Savoy so god only knows what they could have done to Katherine), the two ended their relationship with John being forced to publicly renounce Katherine, admit his sins and reconcile with his wife. It was awkward and public and mortifying and I cannot imagine how it must have felt for Katherine and John who were by all accounts genuinely in love. With the affair over, Katherine returned to Kettlethorpe however spent significant time in Lincoln where she maintained a residence close to Lincoln Cathedral. Now despite the fact the relationship was officially over, at least in the eyes of the public, I don’t think it actually it was. I mean it’s likely the physical aspect of their relationship ceased to continue (no more children were born after 1381), but emotionally I’d say the two were still very much together. John it’s believed visited her discreetly throughout the 80’s, she was frequently at court with John’s nephew the King Richard II becoming rather fond of her, she remained close to John’s children and had a particularly good relationship with John’s daughter in law Mary de Bohun even becoming a member of her household at one point and in 1387 Katherine became a member of the Order of the Garter, the prestigious order of chivalry founded by John’s father Edward III. Before Katherine only 19 women had been made a Lady of the Garter and all of them had been either royalty or very high ranking/wealthy members of the aristocracy. Clearly Katherine was still very much in the royal fold. I mean John’s own brother Thomas of Woodstock allegedly commented in the mid 1380’s that his brother was a fool for loving Katherine so utterly and enduringly, which I think is rather romantic. In 1386 John and his wife Constance decided to finally press their claim for the throne of Castille; in order to fund the campaign and gain support against Constance’s cousin King Juan I of Castille, England entered into a political alliance with Portugal who plead their support (said alliance is still technically in place and is the oldest continuous alliance between two nations in world history). John’s daughter Philippa who Katherine had practically raised as her governess was married to the King of Portugal to cement the alliance. Whilst the marriage was a success (Philippa was a well loved and popular Queen and produced quite a few children who became known as the “Illustrious Generation” in Portugal), the campaign however was not and after a rather botched attempt at invading Leon, John and Constance decided to declare a truce with her cousin. Their daughter Catherine was married to his son Henry thus bringing both sides of the Castilian dynasty together. Following their return to England, John and Constance separated (they had married with the intention of becoming King and Queen of Castile, and with that no longer an option, there was no need to remain together) and John wasted absolutely no time, none whatsoever in asking Katherine to once again become his mistress. Katherine accepted (shocker) and the two were together from then on; although they remained discreet it was an open secret that she was his mistress once more. Politically the two were on safer ground; following John’s return to England, he reconciled with the King and was from then on a moderating influence on the chaos that frequently engulfed English politics. In 1394 his wife Constance unexpectedly died leaving him a widower again; at this point England was domestically at peace and finally stable and so the King began considering a truce with France (although John’s brothers the Dukes of York and Gloucester were not exactly happy at the idea). It was suggested that John as a widowed prince marry again possibly to French royalty to cement the truce; we have no idea how John or Katherine felt about the matter. What we do know is that in 1396 two royal marriages took place; the first was between the 29-year-old King Richard II who married Isabella of Valois (the six year old daughter of the French King) and the second was between John of Gaunt and Lady Katherine Swynford, thus catapulting Katherine from mistress to wife. The two married at Lincoln Cathedral on the 13th January and with that Katherine became the Duchess of Lancaster. Not only did the marriage make Katherine the highest ranking lady in the land (Richard and Isabella’s marriage didn’t happen until months later and so without a Queen, Katherine took the top spot) but with the approval of Richard II and the Pope, the marriage also made John and Katherine’s four children legitimate a fact which would go on to have MAJOR repercussions in English and Scottish history (the Stuart dynasty was descended from their granddaughter Joan who was the wife of James I King of Scotland & mother of James II, whilst the Tudor dynasty based their claim to the throne on the fact that Henry VII’s mother Margaret was John & Katherine’s great granddaughter. Interestingly enough whilst both sides of the House of Lancaster claimed descent from them, they were also ancestors of the House of York side of the War of the Roses with Edward IV and Richard III’s mother Cecily being John and Katherine’s granddaughter through their daughter Joan. In fact all of claimants to the throne of England during the War of the Roses – Henry VI, Edward IV, Richard III & Henry VII – were descended from John whilst three of them were descended from Katherine). Months after their marriage when John’s nephew the King married Isabella of Valois, Katherine accompanied him to France and was a member of Isabella’s household, helping the poor girl who at the age of six found herself Queen in a foreign country married to a man twenty-three years older than her. Katherine and John would not be married for long; John died in 1399 just three years after their wedding however their relationship at this point was nearing the 30 year mark. He was buried besides his first wife Blanche at St Paul’s Cathedral (her fortune had been the foundation of his power, wealth and infamy and she was the mother of his heir, so it’s not surprising he was buried besides her; politically speaking she also wasn’t as controversial as Katherine). In the aftermath of his death, John’s nephew Richard II blocked John’s son Henry from inheriting John’s land and titles, leading to Henry and a good portion of the English aristocracy who were tiring of the king’s shenanigans staging a coup against Richard who was overthrown and imprisoned with Henry taking the throne for himself. Interestingly enough Richard was imprisoned at Pontefract Castle in Yorkshire (where Katherine had been in hiding during the Peasants Revolt 18-years earlier) with none other than Katherine’s son from her first marriage Thomas Swynford serving as his jailer. Richard it’s believed later died after being starved by Thomas on Henry’s orders. Ah nothing like a bit of murder to keep step-brothers close. Henry was crowned on 13th October. There’s no mention of if Katherine was present at the coronation or how close she was to Henry after he became King. The relationship was likely civil although it’s been alleged that he did interestingly try to block John and Katherine’s children from being in the line of succession after him. Allegedly he felt that John had favoured his children with Katherine over his other children. Despite this both Katherine’s son Thomas and her and John’s eldest son John Beaufort were close companions of Henry throughout his reign. Regardless Katherine was well looked after, following John’s death and upon her own demise in 1403, was buried in Lincoln Cathedral, the same place they’d married seven years earlier. Their daughter Joan was later buried besides her. I absolutely adore Katherine and John as a couple. They seem to have genuinely loved each other and despite a barrage of obstacles thrown at them, their relationship appears to have endured to the end. Not only that but almost a century after their marriage, their descendants would emerge victorious from the War of the Roses with the crown of England on the head of their great-great grandson Henry VII.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this. I’ve been very slack on publishing blog posts I’m aware however I’ve got some almost finished posts ready to go that I’m sure you’ll enjoy. See you soon, thank you for reading!

Alexandra.

One thought on “The King’s Mistress”