Welcome to the third and final part of my profile into the legend that is Hürrem Sultan. I am so unbelievably sorry about the delay! I was in hospital for a while and then I went straight into quarantine during which I’ve struggled to find the motivation to complete this profile and then it didn’t feel right to release this post considering all that’s been going on in the world in the last two weeks, however here we finally are!! To recap where we left off in part 2, Hürrem was breaking rules, left right and centre, doing significant philanthropic work in the capital, looking fabulous in expensive clothes, making political allies, advising her husband, raising her children and preparing them for public service. Following Ibrahim’s death, she had found herself unrivalled in Süleyman’s inner circle, a fact she herself pointed out when she wrote to Isabella Jagiellon that, “I am the person most close to the Emperor”. Essentially by the time the 1540’s hit, Hürrem had pretty much become a political force of nature. Being a political force of nature however did not automatically secure her son’s place on the throne and that was the ultimate goal Hürrem would dedicate the latter part of her life to. Which son you may ask? Well as previously mentioned, Hürrem was not your average imperial baby mama. In the year 1540 she had not one, not two but four living sons, all of whom under Ottoman law, had equal right to her husband’s throne (although her youngest Cihangir was disabled and thus unlikely to inherit). She also had a rather irritating yet incredibly popular and formidable step-son Mustafa who had a mother equally as devoted to her son’s future, as Hürrem was to the future of her boys. That poised a significant problem. It also created a particularly uncertain political environment, especially for Hürrem who was more than aware that the survival of her sons rested solely on whether or not, she could secure the throne for one of them. Mehmed, it is obvious, was her & Süleyman’s first choice. He was their firstborn and their golden child, an acknowledged fact even back then. Sultan Mehmed IV as he would have been, however was not to be and in 1543 he died of some sort of fatal illness, the exact nature of which is unclear.

Hürrem and Süleyman as you can imagine were understandably heartbroken. As Leslie P Pierce writes, “”Suleyman’s grief over the loss of Mehmed was legendary. Utterly distraught during the prince’s burial, the Sultan wept for more than two hours, refusing to let the body be interred; he then attended prayers for the dead for forty days instead of the customary three” [1]. Hürrem’s grief is less documented; per tradition she did not attend any public funeral or ceremony and her mourning was therefore private. I need to emphasise as a side note, that Mehmed was NOT poisoned by Mahidevran. Although television adaptions of the story, have resorted to turning Hürrem and Mahidevran into power-hungry murderers who slaughtered each other’s sons, the reality is far different, and it’s clear that Mehmed’s death was a natural one. Hürrem and Süleyman’s love for their son, already an acknowledged fact, became even more obvious when when they decided to build a memorial mosque in his honour. This mosque which became known as the “The Mosque of the Prince” was noted for two things; the first was it’s size and plan, as it was far grander than the tombs usually built for almost-sultans who were traditionally entombed in Bursa. The second notable aspect of the mosque was it’s location; it was in the capital itself and not in a regional province. Princes were never buried in the capital, in fact Sultan’s were traditionally the only imperial family members to be buried in the capital. Before Mehmed, Süleyman’s mother Aÿse Hafsa had been the sole exception. Mustafa Ali, a 16th century historian known for his critique of Hürrem’s political involvement, commented that the mosque’s location and size were a clear indicator of the great love Mehmed’s “fortune favoured mother and illustrious father felt for him in their hearts” [2].

With Mehmed gone, she had to turn her attention to her other sons. Now, there’s a great deal of debate about which of her boys, she favoured in the wake of Mehmed’s death; some say she wanted Selim her second son to succeed his father because she believed that due to his sensitive nature, she could persuade him to spare his brothers lives, whilst others (Selim included) believed that she favoured her third son Bayezid. Süleyman evidently didn’t seem to have a favourite; Mehmed had been his only choice and with his golden boy dead, he seemed content to let the usual fight for the throne commence. Personally I’m torn on which son Hürrem favoured because some of her actions clearly indicate a soft spot for Bayezid however from what we know of him, he was quite unlikely to let his brothers live. Selim on the other hand does appear to be a softer character and I can buy the theory that Hürrem thought he’d be a tad more merciful. Regardless of which son, she favoured, getting one of them on the throne ahead of their half-brother Mustafa was quite frankly a herculean task but if anyone was capable & ruthless & shrewd enough to get the job done, it was Hürrem. She did however face an uphill battle, mostly due to the fact that Mustafa was a very popular guy. He was loved by the people, adored by the army, respected by foreign diplomats and dignitaries and unlike Hürrem, his mother Mahidevran was not a controversial figure (which was considered a plus for him). It was noted by contemporaries that even Süleyman, acknowledged that Mustafa was the most likely to succeed him. Plot Twist: HE DIDN’T.

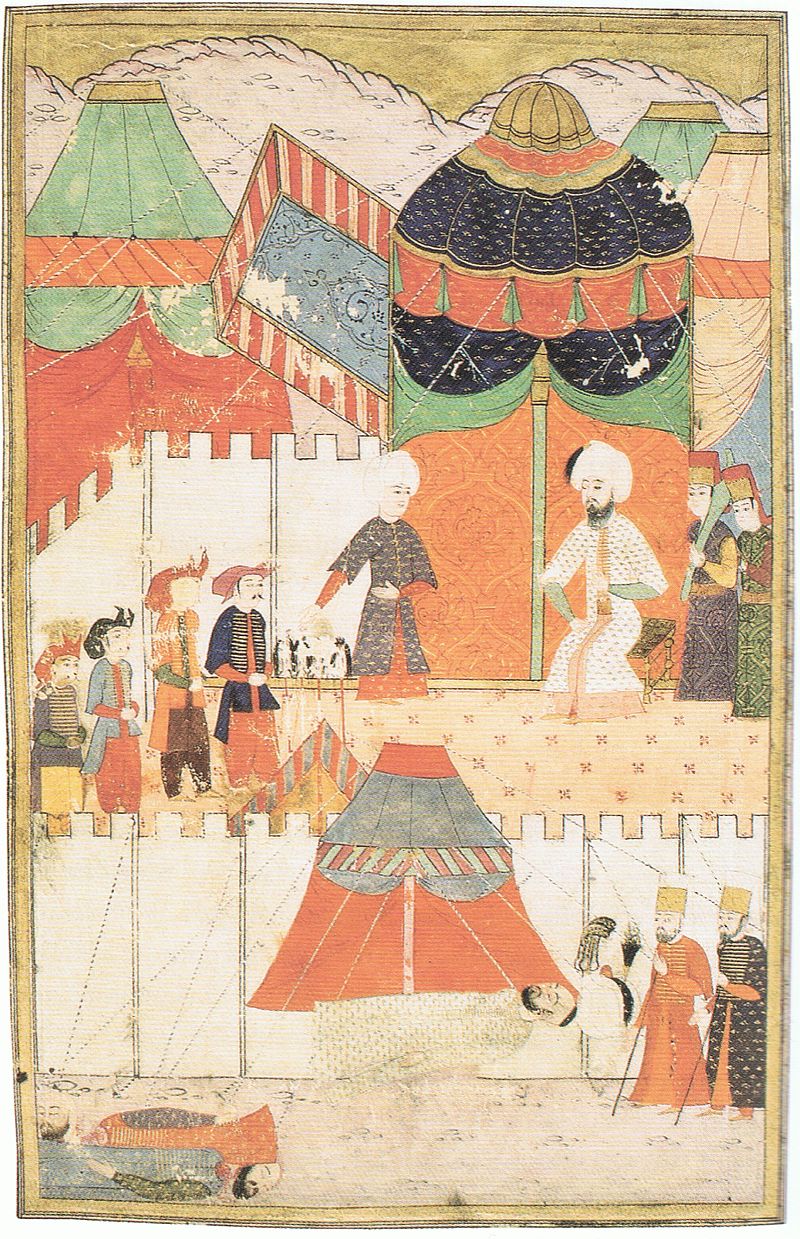

You see, following Mehmed’s death in 1543, Süleyman seems to have lost his appetite for war and for a few years he pretty much remained by Hürrem’s side in the capital. In 1551 however he embarked on the Persian campaign defending the empire’s Eastern border, leaving her as the highest ranking member of the dynasty in the capital. As a side note Hürrem played a super important role whenever Süleyman was on campaign; whilst she wasn’t officially regent, she acted as his eyes and ears essentially overseeing government, the dynasty and the capital. Surviving letters between the two attest to the fact that Hürrem kept him updated on what was going on elsewhere. On the 6th October 1551, during the Persian campaign, Mustafa was summoned by Süleyman to his war camp in the Eregli valley. Upon his arrival, he was taken to his father’s tent, asked to remove his weapons and then instructed to enter where his father was waiting for him. Süleyman however was not the only one waiting for Mustafa. As he entered the tent, he was attacked by a number of Süleyman’s guards and strangled with a bow string, with his own father allegedly watching from behind a screen. Ouch. Below is a depiction of the aftermath of the execution by Seyyid Lokman.

So the question of why Süleyman executed his son, is an open debate and there’s really no clear answer. The official reason was that Mustafa had become a threat to Süleyman’s rule. You see the Osman family had somewhat of a history of young, ambitious princes forcing their elderly fathers to retire; Süleyman’s father Selim I had done exactly that to Süleyman’s grandfather Bayezid II who died (allegedly poisoned) on his way to where he intended to live out his retirement. Following that “retirement”, Selim had faced resistance from his brothers who he then proceeded to put to death per Ottoman tradition. Selim’s slaughter of his brothers and nephews was one of the larger enactments of the fratricide policy and forty years later in 1551, the bloodshed from that moment in Ottoman history was still pretty fresh. Everyone remembered the bloodshed and everyone including Süleyman himself, certainly remembered what his father had done to his grandfather. A guy as wise as him knew that “the prospect of Mustafa ‘retiring’ his father and initiating a war for the succession was not implausible. Mustafa’s popularity only exacerbated that threat”[3]. Whilst we don’t know if Mustafa was actually plotting against his father (I think it’s unlikely; after 30 years on the throne Süleyman was still pretty popular), it’s possible that those around Mustafa were. And even if they weren’t, Mustafa’s popularity both with the people and the military and Süleyman’s increasing age could potentially have hindered his ability to rule effectively. Something that Süleyman was evidently not willing to risk.

In terms of my personal opinion, I happen to think that the execution of Mustafa was an incredibly complex situation and there were probably issues and situations and interactions behind the scenes, both personal and political, that were not made public and that we’re unaware of. I mean we’re not even 100% about the nature of Süleyman and Mustafa’s relationship. Whilst some of Süleyman’s and Hürrem’s letters survive, we have none that concern Mustafa and certainly none from Mustafa to Süleyman or vice versa. This combined with the fact that most of the surviving contemporary material is written either by someone who was clearly Team Süleyman or in the case of Taslicali Yahyâ bey, someone who was very clearly Team Mustafa, makes discerning the facts, fairly difficult. I do think Mustafa was a potential threat to Süleyman, particularly in regards to his relationship with the very-powerful Janissaries, and Süleyman may have felt the need to eliminate that threat. It may seem over the top to us in 2020 but it is somewhat politically understandable in that era and in that context. Also if Süleyman and Mustafa’s father-son relationship was breaking down or already irrevocably broken, I understand the former’s mistrust of the latter. In regard to Hürrem’s involvement, I tend to look at it like this. Was she solely responsible for Mustafa’s death? No. Did she contribute? Probably. At the end of the day, her number one goal was the survival of her sons and Mustafa’s death achieved that. I do think that if Süleyman was concerned that Mustafa was a threat to him, she probably encouraged that concern however ultimately he was the one that called the shots and he was the one that ordered the execution. Blame lies with him. No-one at the time however would have been bold enough or quite frankly stupid enough to outright blame Süleyman, so blame seems to have been shifted onto Rustem Pasha; Süleyman’s aforementioned Grand Vizier, Hürrem’s partner-in-crime and their daughter Mihrimah’s much older husband. Shortly after Mustafa’s death, Rustem was removed from his position and suffered a somewhat humiliating fall from grace, being replaced by Süleyman’s brother in law Kara Ahmed Pasha. Rustem remained out of favour for a while but certainly not for long. Whilst Rustem was considered the main villain in the death of Mustafa, some corners of the empire did certainly suspect Hürrem’s involvement however Süleyman had made it abundantly clear he didn’t appreciate slander against his wife (Luigi Bassano once wrote that no spoke ill of her for fear of angering the Sultan) so no one openly accused Hürrem of murder. In the centuries afterwards however the narrative of Hürrem as the grand architect of Mustafa’s death became a popular one, forever tarnishing her reputation. This narrative somehow became a universally agreed fact, not just within the Ottoman Empire but in Europe as well and if you want to read more, Galina Yermolenko’s essay “Roxolana in European Literature, History and Culture” goes into great detail about the European obsession with Hürrem and how she was culturally portrayed in the centuries after her death. Rustem’s replacement Kara Ahmed Pasha was no friend of Hürrem’s and when two years later, he was executed for treason, she faced accusations of orchestrating it. I actually happen to understand why people would think Hürrem was responsible; she hadn’t been subtle in her favouritism of Rustem and had basically spent two years openly encouraging Süleyman to forgive their son in law and restore him to the position of Grand Vizier. Which coincidentally, was exactly what happened after Kara Ahmed’s death. Once again, as with Ibrahim and Mustafa’s deaths, I suspect Hürrem supported the execution and probably/possibly even encouraged it but to place blame solely on Hürrem is to absolve Süleyman of any blame, despite the fact that officially he was the one that ordered all three deaths. We’re in 2020 people, stop blaming a woman for a man’s choice.

With Mustafa out of the way, government full of her allies and the future of her boys at least mostly secure, Hürrem was able to continue her extensive and quite frankly groundbreaking charity work, endowing the holy cities of Mecca and Medina with hostels for pilgrims and ordering the construction of the Haseki hospital in the capital. Her charity work culminated in the most famous of her philanthropic efforts; the construction and opening of charity complexes in the holy city of Jerusalem, a great honour for a Muslim queen. Her endowment in Jerusalem was particularly notable, not just because she was the first female member of the House of Osman to venture into the holy city but also because it placed her on the same pedestal as other notable queens who had contributed to the skyline of the city; women like Helena the mother of the Byzantine emperor Constantine the Great, Khayzuran the mother of Abbasid caliph Harun the Just and Zubaida, Harun’s wife. Zubaida was actually referenced in the charter deed of of Hurrem’s charity complex as were the Prophet Muhammad’s first wife Khadijah, daughter Fatima and third wife Aisha, three of the most venerated female figures in Islam. Decades after her death, Hürrem’s philanthropy would be compared to theirs, with her humanitarian work being celebrated by many including Talikizade Mehmed who wrote, “The Lady of Time has not seen such an abundantly benevolent dame”[4].

She also had a growing family to occupy herself with; excluding Cihangir (who died not too long after Mustafa’s execution), all of Hurrem and Süleyman’s children had offspring of their own and the couple were particularly doting grandparents. Two of their granddaughters Ayse Humasah Sultan and Hümasah Sultan (like the Europeans, the Ottomans liked to stick to the same traditional names) were extremely close with their grandparents and both girls would grow up to demonstrate the brilliance of their grandmother, becoming pretty influential in imperial politics. Hürrem and Süleyman building this sort of devoted nuclear family was such an anomaly in Ottoman history and no Sultan ever attempted it again. Hürrem and Süleyman’s devotion was not just to their children but also to each other; in the 1550’s after three decades together, Süleyman remained faithful with Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq a Habsburg envoy writing, “it is generally agreed that, ever since he promoted her to the rank of his lawful wife, he has possessed no concubines, although there is no law to prevent his doing so”[5]. Not only did he continue writing very gushing poetry about her under the pen name Muhibbi (you can find examples online), he would also continue to honour her as his partner both in life and politics, and in around 1556, to demonstrate her place of authority within the dynasty, he increased her daily stipend, upping it from 1,000 aspers a day (already unprecedented in the harem) to 2,000 aspers, significantly more than any allowance in the Ottoman records, even higher than the allowance of Süleyman’s himself. By this point, Süleyman (who had turned 60 in 1554) pretty much relied on Hürrem and to emphasise just how influential she had become, the French ambassador wrote after her death that, “the majority of those who govern the empire were of her making” [6]. Kutbeddin wrote that she had “influenced the Sultan to such a degree that the state of many affairs lay in her hands”[7]. This sort of power is incredibly impressive considering she entered the palace a slave, a piece of property, something to be owned and degraded and demeaned. No one however is immortal and in the mid 1550’s Hürrem’s health began to decline. What illness she had, we have no idea. What we do know is that it seemed to be a chronic condition of some kind; both Kutbeddin and the Venetian ambassador Antonio Barbarigo mentioned her illness with the former writing that she had been suffering from her illness for quite a while whilst the latter informed the Venetian senate that Hurrem, “was the mistress of the life of this gentleman, by whom she was extremely loved. And because she wants him always near her and is doubtful for her own life on account of illness, she rarely or never lets him part from her”[8]. Evidently the illness was serious enough that Hürrem feared dying alone and Süleyman, not a man known to deny her anything, refused to leave her side.

Around this time, there was a lull in military campaigns, a result of Hürrem’s faltering health and Süleyman’s own increasing age. However on April 15th 1558, an Ottoman naval fleet left the capital and traveled to the Med where in 1560 they would win the Battle of Djerba. That same morning, Hürrem had passed away in the early hours with Süleyman by her side. Thus came to the end, one of the most incredible life-stories of the 16th century. She had gone from slave to empress in just a few years, had played a role in the complicated international politics of the 1500’s, had turned the great House of Osman completely upside down, had left a significant material legacy to the people in the empire she had helped to govern and would go on to be the ancestor of every Ottoman Sultan that came afterwards. She would also be the founder of the Sultanate of Women, an approx 150 year period where women of the harem were the ultimate power players in imperial politics. It was Hürrem that effectively created the dynastic conditions that allowed future women such as Kösem Sultan and Turhan Hatice Sultan to rule as regents. To say that Süleyman was heartbroken by his wife’s death, is somewhat of an understatement. He was devastated and he remained that way, becoming increasingly isolated in the last few years of his life, relying mostly on their beloved daughter Mihrimah who had inherited a little of her mother’s brilliance. As Kutbeddin said in his eulogy of Hürrem; “the Sultan loved her to distraction and his heart has broken with her death” [9]. Süleyman also remained loyal to the memory of his wife. The man who had been utterly faithful to her in life, remained so in death, and it’s believed that in the eight years from Hurrem’s death in 1558 to his own in 1566, he refused all other women, which to be honest is vaguely heartbreaking. He was certainly never the same and when he died, he was buried in a domed mausoleum adjacent to the mausoleum where Hürrem had been laid to rest. Their daughter Mihrimah would join them a number of years later as would two future Sultans Ahmed II and Süleyman II (both of whom were Hürrem & Süleyman’s great-great-great-great grandsons).

Her death had immediate repercussions on the imperial family; not only was Süleyman heartbroken but the rivalry between their sons Bayezid and Selim seemed to reach boiling point. It would appear that whilst Hürrem was alive, she had been able to manage her sons ambitions and keep their dual desire for the throne under control however with her gone, it all descended into chaos, culminating in her third son Bayezid actually rebelling against his father. And by rebelling I mean, refusing to follow his father’s command and then meeting his older brother with an army. Selim and Bayezid’s mini-civil war took place in May 1559, just a year or so after their beloved mother’s death and after losing, Bayezid made the HORRENDOUS decision to flee to the Ottoman’s empire greatest enemy the Persian’s. This was such a stupid decision on so many levels, a fact Bayezid became aware of when the Persian’s jailed him on the request of Süleyman who proceeded to pay the Persian monarch Shah Tahmasp I for his son. When Bayezid was eventually handed over to the Ottomans, he was executed on charges of treason, as his elder half-brother Mustafa had been eight years earlier. With Bayezid dead, Selim was now the sole heir to the throne and on Süleyman’s death in 1566 he became Sultan Selim II or “Selim the Blonde” as he became known (clearly he inherited his mama’s fair colouring). He’s seen in the image below. With no mother to serve as Valide Sultan, his sister Mihrimah did, replacing her mother as the empire’s highest ranked woman. Although she never became Valide Sultan, Hürrem was able to achieve what she had had ultimately dedicated her life to; getting one of her sons on the throne and with both of her surviving children; her powerful daughter and ruling son, her legacy was secure.

So many of the historical women that have films and tv shows made about were born to wealth and privilege; Hürrem however was the ultimate Cinderella story. To have the tenacity and bravery and intelligence to go from slave to concubine to empress is just the most unbelievable thing and it’s women like Hürrem that make studying history all the worth while. I also think Hürrem perfectly encapsulates how history has struggled to view women as the nuanced and complex humans they are. Reading about Hürrem or watching anything about her is wild because she’s either portrayed as a master manipulator who was pulling all the strings and controlling her husband or she’s a passive bystander who was merely a scapegoat for the less than popular decisions of her husband. Hürrem was not a caricature of an evil step-mother nor was she a naive lamb. She was a fiercely intelligent, ambitious, determined, protective mama bear who did both good and bad to secure her children’s future whilst simultaneously re-writing the roles of women with a very strict system. She was complex and fascinating and if anyone in Hollywood is looking for such a woman to make a movie or tv show about, then here’s the woman you’re looking for!

There it is! I hope you enjoyed this (extremely late!!) final post on Hürrem. I promise you the next post will not be delayed! See you soon.

Alexandra x

References

[1] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 235.

[2] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 239.

[3] Leslie Peirce, “The Imperial Harem: Women & Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 81.

[4] Talikizade Mehmed qtd in Gülru Necipoglu, “The Age of Sinan:Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire”, (Princeton, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 2005), p. 269-271.

[5] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 245.

[6] Ernest Charriere, “Negotiations de la France dans le Levant Volume 2”, (Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1848-1860), p. 464-465.

[7] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 303.

[8] Eugenio Alberi, “La relazioni degli ambasciatori Veneto al Senato”, Series 3, Volume 1, (Florence, 1840)

[9] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 303.

3 thoughts on “HÜRREM SULTAN // She Came, She Saw, She Conquered // Part 3.”