Welcome to the second part of my profile of the amazing Hürrem Sultan. When we left off in Part 1, Hürrem had it pretty great; she was the unrivalled favourite of the Ottoman sultan Süleyman I who had forsaken all others and become pretty much faithful to her and her only, they’d broken centuries of tradition by having five sons and a daughter instead of the normal one son per concubine, and he was becoming a major force in international politics after just a few years on the throne. Within a few years of their relationship becoming monogamous however, Süleyman would not be the only one making their mark politically; after spending the 1520’s bearing his children, grieving the loss of one son Abdullah and focusing solely on her role as Süleyman’s favourite, Hürrem began to emerge in the 1530’s as a political force of nature in her own right. What prompted this unprecedented step into imperial politics you ask?

It might have had something to do with the fact she went from concubine to wife. Yes you heard me correctly – HE MARRIED HER!!!! This was such a tectonic shift in tradition that it’s difficult to fully emphasise how shocking it was to people, both within and outside the empire. After all, Sultan’s didn’t need to marry their concubines, and no Sultan ever had. What made this marriage possible, was the death of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) Ayse Hafsa in the spring of 1534; it’s highly unlikely Süleyman would have married Hürrem and thus elevated her above his mother whilst the latter was still alive. Ayse Hafsa was a representative of tradition and her imperial career had been very much in line with the rules of the dynasty. Her death, was effectively the beginning of both Hürrem’s political career and thus a new era of imperial politics. Within two months of her death, Süleyman had not only freed Hürrem (he had to free her of her slave status in order to marry her) but had also made her his legal wife, and thus dawned the beginning of the new regime. The wedding was reported by ambassadors including the Genoese ambassador who wrote the following in dispatches back to Italy.

“This week there has occurred in this city, a most extraordinary event, one absolutely unprecedented in the history of the Sultan. The Grand Signor Suleyman has taken to himself as his Empress, a slave woman from Russia, called Roxelana, and there has been great feasting. The ceremony took place in the Seraglio and the festivities have been splendid beyond all record…. There is great talk all over this country about this marriage and none can understand what it means” [1]

Süleyman followed up his unprecedented marriage with two other monumental changes; firstly he gave her the shiny new imperial title of Haseki Sultan which roughly translates to “the first princess of the state”. She was the first concubine to use the title of Sultan which was usually only used by the Sultan’s mother or blood relatives such as his sisters. I cannot emphasise enough that before Hürrem and Süleyman became man and wife, the title of Haseki Sultan did not exist. In order to elevate Mahidevran, she is often referred to as a Haseki by scholars, despite the fact there’s no evidence the title ever existed before Hurrem. There is however a wealth of evidence that demonstrates the title was created by Süleyman solely for his new wife. She was the first holder of the title and effectively the empire’s first (and only) Empress. The second monumental change in the aftermath of their marriage was that Hürrem left the Old Palace and moved directly into the New Palace with grand apartments that connected to Süleyman’s. This was huge because no woman had never lived in the New Palace before; it was where the Sultan lived and where politics was conducted and power held. The Old Palace was the dominion of the dynasty’s female members and the separate palaces was a way of keeping women separate from power. For the first time in Ottoman history, Hürrem had broken down that wall and not only was a woman now in close physical proximity to the Sultan constantly but she was also within touching distance of the offices of government. This would be the beginning of the era of the Haseki; a period where the Sultan’s favourite exerted significant influence on the court and in the years that followed, Hürrem became a major power player within the empire. She was Süleyman’s partner, not just in personal affairs but political ones too and when he was away from the capital, she was his eyes and ears, keeping him fully aware of the political climate in the city. She was not however the only significant confidante of Süleyman.

This guy. This guy right here is Ibrahim Pasha and if you’ll recall I did mention him all the way back at the beginning of part 1. He’s the guy that may or may not have been the one to bring Hürrem into the harem in the first place. You see, Ibrahim had been Süleyman’s closest friend since their youth despite the fact that he like Hürrem had been a slave when he had first met the then-prince, and the two were still in the 1530’s remarkably close. In fact Süleyman had promoted him so spectacularly that Ibrahim was not only the Grand Vizier (effectively Prime Minister), but he was also the second richest man in the empire and the second most powerful, behind the Sultan himself. Now Hürrem and Ibrahim make a fascinating duo because they were basically two sides of the same coin. Both had engineered stratospheric rises from slave to major power player, both had circumvented the usual path to power, both were incredibly shrewd, intelligent and ambitious and neither had cultivated a particularly good relationship with the public. In fact both Ibrahim and Hürrem were controversial amongst the Ottoman populace who believed Süleyman relied too much on his wife and best-friend and allowed the two, far more power than either should have. Venetian ambassadors noted that Ibrahim was hated by pretty much everyone [2] whilst by 1540, accusations of witchcraft were being levelled at Hürrem, alleging that she used potions and spells to maintain his devotion, which in 1536 after almost two decades together, was as strong as ever. We know frustratingly very little about the relationship between Hürrem and Ibrahim although a letter from Hürrem to Süleyman in 1526 would suggest there were at the very least moments of tension between the two favourites, with Hürrem writing, “an explanation has been requested for why I am angry at the pasha. God willing if it becomes possible to speak in person, it will be heard”.[3] Although this suggests some tension, it hardly fits into the narrative that the two were fierce rivals who fought bitterly not only for Süleyman’s attention but also for power. This narrative of a fierce rivalry probably stems from the issue that would end up being the most significant of Hürrem’s life.

The matter of succession.

Remember in part 1 when I mentioned that under dynastic rules, each and every prince had equal right to the throne? Well that meant that if Süleyman and Mahidevran’s son Mustafa inherited the throne instead of one of Hürrem’s boys, then not only would Hürrem and her daughter potentially be exiled and left with nothing but all four of her living sons would be slaughtered in order to prevent any domestic strife. If she wanted her children to survive, Hürrem needed to make sure one of her boys would succeed their father. There was just one Ibrahim-sized problem. Ibrahim as Süleyman’s closest friend and highest ranked minister was basically the co-captain of Team Mustafa alongside Mahidevran and his wealth and influence was a massive boost to the prince, who in the 1530’s was young, handsome, popular and had already per tradition been sent to govern a regional province. This gave him the upper hand over Hurrem’s princes who were a) still children b) still living in the capital with their parents and c) had a mother who was particularly controversial. In January 1536 Süleyman and Ibrahim returned to Istanbul after a military campaign in Iran and it was evident that there was at least some tension between the Sultan and his pal at the time of their return; probably a result of concerns about Ibrahim’s leadership during the campaign. Within just two months however, Ibrahim was dead. Executed in the centre of the palace, allegedly in the middle of the night, at the orders of his Sultan.

Why Süleyman ordered Ibrahim’s death, we will never actually know for certain. Historians have certainly never been able to come to an agreement. I tend to share the view of many that Ibrahim had simply committed too many errors in the years leading up to his demise. As I mentioned, there had been concerns over his handling of the Iranian campaign, but he’d also executed the immensely powerful treasurer Iskender without checking with Süleyman first, he was publicly despised to the point where Janissaries had targeted his palace in 1525 and his loyalty to Islam had been called into question by both Muslims and Christians alike. This I believe had put him in a precarious position and in the words of Leslie Peirce, “in the end Ibrahim’s errors clearly accumulated to the point that Süleyman found it necessary or expedient to get rid of him”[4]

I’d like to emphasise the last portion of that sentence. Süleyman found it necessary to get rid of him. Note, it does not say Hürrem. In the centuries since, Ibrahim’s death has been presented as the culmination of a years long feud between the pair, and that Hürrem had long schemed to make his death a reality. The thing is, is that there is literally no evidence of this and foreign ambassadors at the time had no opinions as to whether Hürrem was involved, nor did the Ottoman public seem to blame her. At the same time, it’s unlikely she hadn’t offered Süleyman advice on the matter. It’s difficult to gage just how involved Hürrem was in Ibrahim’s demise however the notion that Hürrem was solely responsible is just plain ridiculous. Süleyman ultimately made the decisions and portraying him as a fool that was manipulated by his wife into executing his best-friend does not only him a disservice but also their relationship. My personal opinion is that Hürrem, being the fiercely intelligent politician she was, knew that Ibrahim’s death would leave Mustafa without his most powerful supporter, and therefore probably encouraged any negative feelings Süleyman had clearly developed towards Ibrahim. In other words whilst it’s HIGHLY unlikely she outright called for his execution, I doubt she argued against it either, and considering that Süleyman obviously valued her opinion, I would at best call her a contributing factor to his demise. Far more integral to his death, were his own poor choices.

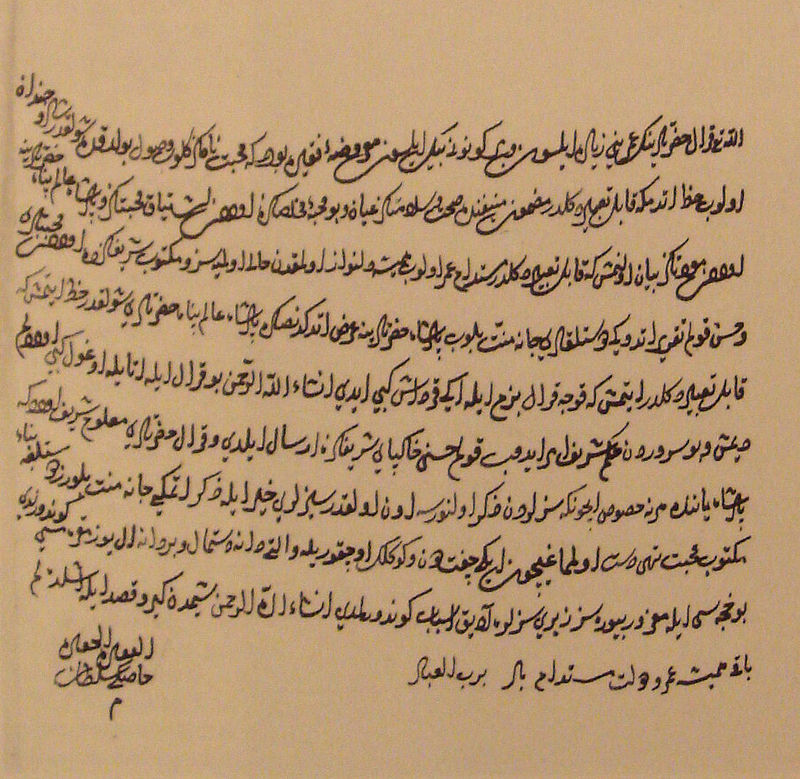

Now in the aftermath of such a imperial shake up, Hürrem found herself the only person that was particularly close to the Sultan and she soon began flexing her foreign policy muscles, engaging in politics on an international level. She began correspondences with various European monarchs in particular Bona Sforza the Queen Consort of Poland (another fascinating woman you should take a look at), both Bona’s husband Sigismund I King of Poland and son Sigismund II Augustus King of Poland and Bona’s daughter Isabella who became Queen of Hungary in a political alliance supported by Süleyman and therefore Hürrem. Several letters between the two dynasties remain including one (seen below) where Hürrem congratulates Sigismund II Augustus on his accession to the throne. Hürrem and Süleyman’s daughter Mihrimah (a girl that would go on to inherit her mother’s political prowess) would also go on to communicate with the Polish royals creating close ties between the two dynasties; at the core of that close relationship was Hürrem and Bona and the formidable duo’s influence on their respective spouses. Whilst the consort of the Polish monarch conducting politics on behalf on their spouse was not an anomaly, “it was unusual for Süleyman, as an Ottoman ruler, to use his consort for diplomatic purposes” [5]. Unusual is an understatement; a woman being so involved in Ottoman foreign policy and diplomacy was a major diversion from the norm, although in time it would become a vital aspect of Ottoman governance.

Something else that would become the norm for women of the Ottoman dynasty as a result of Hürrem’s trailblazing influence, would be the widespread establishment of charitable foundations in a woman’s name. Although it was commonplace for Valide Sultan’s and high ranking concubines to be the public patrons of small institutions (Süleyman’s mother for example had financed her own charitable project in Manisa where her son had been based during his youth); these institutions were always a) in distant regional provinces away from the capital and b) were established after the concubine had left the capital to follow their son to their regional province. In 1538 however, Hürrem changed the game completely. Not only was her new mosque complex huge but it was located right in the middle of the capital, in a neighbourhood that was associated with females. In fact it just so happened to be a stone’s throw away from the women’s market where she had once been sold. A coincidence perhaps. Or maybe the location was chosen on purpose to remind her and everyone else of just how far she’d come. Regardless, the neighbourhood is to this day known as “Hasekisultan” and is located in the Fatih district of the city. She thus became the first imperial woman in Ottoman history to put on her stamp on the skyline of Istanbul where it remains to this day. The size of the complex would expand over time and would later “include two schools – a madrasa to provide advanced education to older youths and a primary school that taught letters and scripture to children of the neighbourhood. The next structure to rise up was a large soup kitchen. Some years later, the complex gained a hospital, a rare amenity. A fountain on the soup kitchen’s grounds brought fresh water to neighbourhood residences” [6]. Hürrem was extremely involved both in the planning of the complex and in the administration of the complex after it’s completion, and the complex was the first of many that Hürrem would finance. No woman in the Ottoman Empire before Hürrem had built so extensively and few women would after. Hürrem’s philanthropic works would later become legendary and she was said to have a particular desire to help women in particular; whilst this was clearly a personal desire, there was also a political upside to such philanthropic patronage. As previously mentioned, she wasn’t exactly Mrs Popular amongst the public and so Hürrem may have felt that doing copious charity work to benefit said public, was potentially going to help with that popularity or lack thereof. This was a shrewd decision, after all charity work was incredible important in Ottoman society (and Muslim society in general) to the extent that the eulogies/death announcements of public figures usually included the philanthropic works they’d been involved in and so if anything was going to help with Hürrem’s reputation, it was probably charity work. Another factor in Hürrem’s charitable endeavours was that following her marriage she’d become rich. Like super rich, with Süleyman granting her a huge dowry and a daily stipend higher than even his mother. She had money to spare and charity work was the perfect way to spend that money. Side-note she also spent that money on clothes and jewels and was considered a fashion icon. Now who doesn’t love a charitable and fashionable Queen.

Meanwhile she also had a step-son who was becoming incredibly popular, children who were becoming teenagers and a son (Mehmed) who she wanted to be Sultan, to deal with. Mehmed had been her first born and in all honesty seems to have been the favourite child of both Hürrem and Süleyman who adored the boy. He was basically their golden child and this was evident to just about everyone when Süleyman assigned Mehmed the region of Manisa to govern (Manisa is the traditional place for the Sultan to send their favourite son / the one they want to succeed them). In order to assign Manisa to Mehmed, Süleyman had to remove his other son Mustafa who had been ruling there and send him elsewhere. Replacing Mustafa with Mehmed was a fairly clear sign about where his loyalties lay, as did the fact that Mehmed had been by his father’s side for a number of his father’s military successes such as the Siege of Buda (Hürrem’s other sons Selim and Bayezid had also been present) and the Siege of Esztergom, whereas Mustafa had not. Mehmed, it appeared was considered by Süleyman to be his heir and the future Sultan, making Hürrem the future Valide Sultan. Mehmed being assigned to Manisa left the Ottoman people with one question on their lips; would Hürrem go with him? Most imperial mothers did; it was tradition for the concubine to follow her son to their regional province never to return to the capital again unless her son won the throne, however Hürrem as you may have noticed, was not your average concubine. She was a legal wife, a mother of multiple heirs and the Haseki Sultan. She had followed precisely 0% of the empire’s traditions thus far, why would she start now? And she didn’t. She stayed in the capital with Süleyman and her other children, leaving Mehmed to travel to Manisa with a entourage, I’m sure she selected, made up of trustworthy and loyal advisors. She was said to visit her son frequently however her decision to stay with Süleyman made it clear that her place was by her husband’s side, and that’s where she would stay. When her other sons later went to their own regional provinces, she once again stayed behind. This was likely due to her a) not wanting to leave her husband and b) not wanting to show overt favouritism to one of her sons over the others. Whilst preparing her sons for their regional positions, she also had her daughter Mihrimah (seen below) to deal with and in 1539, the 17-18 year old princess was married to Rustem Pasha, a government minister who unlike the dearly departed Ibrahim had risen up the ranks through hard-work and shrewd decisions, not through a close relationship to the Sultan. Rustem was the ultimate bureaucrat who happened to be, like Hürrem, a very talented politician, and the two formed a seemingly unbreakable partnership. It was Rüstem that would be by her side for the most controversial era of her life yet.

So there we are for part 2. I apologise for the delay in this post and promise that the third and final part will be on the site shortly! Thank you and I hope you enjoyed this post.

Alexandra x

References

[1] Leslie Peirce, “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire”, (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 62.

[2] Leslie Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, (New York, Basic Books, 2017), p. 155.

[3] Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, p. 165.

[4] Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, p.163.

[5] Katarzyna Kosior, “Bona Sforza and the Realpolitik of Queenly Counsel in Sixteenth Century Poland-Lithuania”, in Queenship & Counsel in Early Modern Europe, ed by Helen Matheson Pollock, Joanne Paul and Catherine Fletcher, (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), p. 27.

[6] Peirce, “The Empress of the East: How a European slave girl became Queen of the Ottoman Empire”, p 170.

Other Bibliography

1. Aleyv Lytle Croutier, “Harem: The World Behind the Veil”, (New York & London, Abbeville Press Publishers, 1989)

2. Linda Rodriguez McRobbie, “Princesses Behaving Badly: Real Stories from History without the Fairytale Endings“, (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Quirk Books, 2013)

3. Mustafa Metin, “The Iconography of Renaissance Ceremonials in the Early Modern Period”, Australian Journal of Islamic Studies, Vol 3, No.1, (2018), pp 1-23.

4. Walter G Andrews & Mehmet Kalpakli, “The Age of Beloveds: Love and Beloved in Early Modern Ottoman and European Society and Culture“, (Durham & London, Duke University Press, 2005).

3 thoughts on “HÜRREM SULTAN // She Came, She Saw, She Conquered // Part 2.”